1

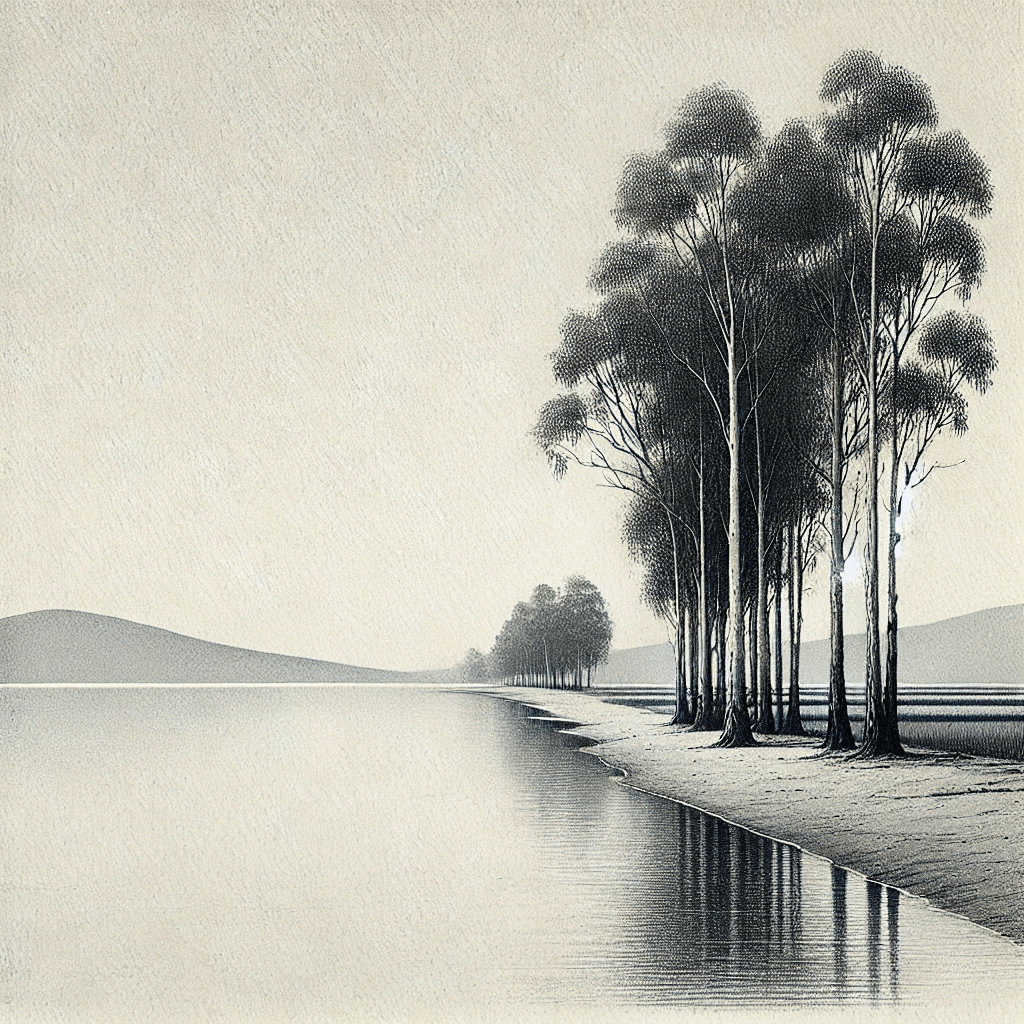

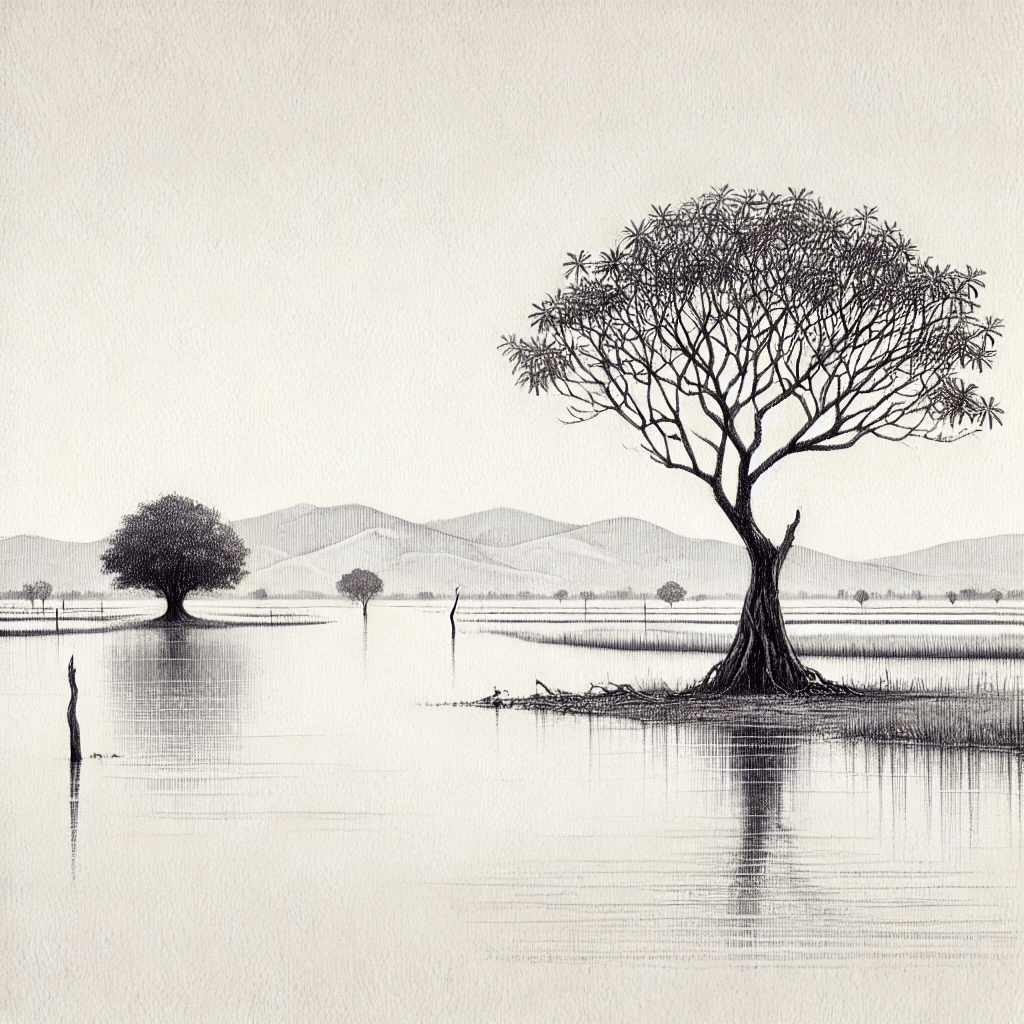

There was a moment when all quieted down—the wind stopped, the waters grew calm, and the tall eucalyptus trees stood still and silent. He thought he had heard something—a faint noise, a muffled cry perhaps. It came, and then it was gone. Perhaps it was never there in the first place. The sky was gray, and far off, where the lake met the distant mountains, a faint mist lingered.

From beneath his arm, he slid out a worn brown envelope and withdrew a single sheet: a hand-drawn pencil sketch, its edges creased and frayed, the lines dulled by time. It was a sketch of the scene where the teenage girl’s body had been found, drawn from exactly the same spot where he now stood.

It was hard to fathom now, but on a July afternoon much like this one, this desolate lakeshore had buzzed with life. Nearly eighty schoolchildren in swimsuits had swarmed the beach, banners fluttering, displays erected to commemorate the second anniversary of Chairman Mao’s swim across the Yangtze River the year prior.

“So this is where they found her,” he murmured, as if to himself. “That July afternoon, long ago.”

He waded through the knee-high shallow water and walked slowly toward the nearest grove of eucalyptus trees on the lakeshore. At the third tree on the right, he stopped. From the envelope, he drew another sheet—a page torn from a pocket notebook, its jagged edge hinting at haste. Written on it were these words:

“Teenage body; female; found face down at the edge of the rice field next to the grove of eucalyptus trees.”

So little had changed around this part of the lakeshore and its surroundings that he was able to match the description in the notes to what he saw. The accuracy was remarkable.

Presently, the wind returned. Waves rippled across the lake, and he could hear the rustling of leaves in the trees. He tugged his uniform collar tighter against the chill, cast a final glance at the spot by the three trees, and turned toward the dirt road where his motorbike waited.

2

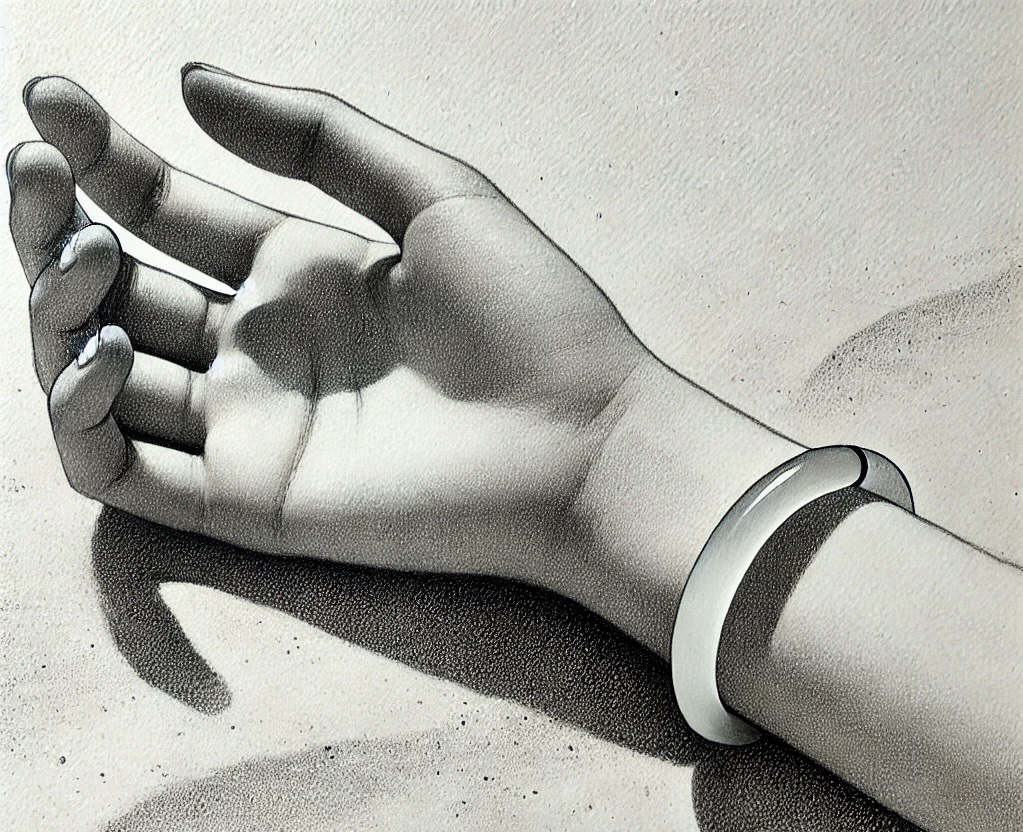

He’d lost count of how many times he’d pored over the case documents sprawled across his desk: three pages of a case briefing, typed on an old Chinese typewriter; two sheets of letter paper, fountain pen ink smudged into blue blotches, a faded “Revolutionary Leadership Group” stamp—now a dull brown—pressed at the bottom; and two pencil sketches—one of the lakeside he’d visited that afternoon, the other an unfinished outline of what he guessed was a woman’s hand. That was it— the entirety of a murder investigation’s remnants.

He sipped his tea and set the cup beside the case folder, a large brown envelope of coarse kraft paper, the kind common in the 1960s and 1970s. The words “Top Secret” were written in blue-black ink across the seal, dated July 16, 1968. His fingertips brushed over the embossed stamp marks on the back—an official seal used exclusively by the Military Control Committee at the time.

The file’s discovery had been a fluke. A week ago, the county police had abandoned their old Soviet-style headquarters—home to the department for over thirty years—for a sleek new building, courtesy of government reforms. On moving day, a trove of old papers was unearthed from that old dungeon they used to call “the Archive,” and among them was this cold case file. It was a document that should have been destroyed during the 1982 file purge, but apparently it wasn’t, and no one at the archive could explain why.

Beyond the window, through a veil of rain, the new five-story office building shimmered with the stark glow of aluminum frames. Clutching a file from an era when he was just entering elementary school, he felt a sudden chill run down his neck.

3

The officer who compiled this file was a Political Commissar of the Military Control Committee (MCC), holding the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. His signature marked every document except the two pencil sketches, which remained unsigned and undated. The typed and handwritten sheets mostly aligned, though their wording diverged slightly—likely the typist had used the handwritten notes as a draft. Together, they offered a sparse outline of a murder:

“Date: July 16, 1968. Location: Lakeshore. Victim: female, aged 13–16, found submerged in shallow water. Cause of death: ligature marks on neck, inconclusive.”

A villager had reported the case to the county police’s MCC. That same day, the Political Commissar conducted a cursory investigation and penned the handwritten notes. Just a day earlier, on July 15, the lakeshore had hosted a public event—an elementary school celebration of the second anniversary of Chairman Mao’s swim across the Yangtze River. Roughly eighty children from three grades, accompanied by their teachers, had attended.

A follow-up with the school confirmed no absences; every student was present the next day. Amid the file’s scant details, one fact stood out: the victim was not a local pupil. In the days that followed, no missing person reports surfaced.

1968 was a turbulent year in China’s history. The Cultural Revolution, ignited just a year prior, had surged nationwide, peaking in ’68. Governments at every level, including police forces, had crumbled, paralyzed by chaos. The military stepped in to impose order, with MCCs assuming control across the country.

In such a climate, the death of a young girl barely registered. Small wonder the case file amounted to just a handful of pages.

4

For two days, work consumed him, the lakeshore murder case nearly slipping his mind. Early Monday, a report of stolen cables at a construction site on the town’s outskirts pulled him in. He led his team through the muddy chaos, crouching to inspect scattered insulation strips. The cuts were precise—professional work.

That afternoon, he pored over footage from three nearby scrap yards. After thirty minutes of squinting at grainy screens, he pinned the vehicle by its tire treads: it belonged to Zhang, a local scrap collector with a familiar name.

Tuesday was meant to be his day off, but the deputy director dragged him into a joint analysis meeting on a spate of burglaries in the next county. En route, he juggled two calls from his wife—still no time to settle their daughter’s middle school placement. By midday, he was squatting outside the local station’s mediation room, waiting for officers to resolve a land spat between villagers so he could check if one tied back to an old suspect.

The moment routine loosened its grip, though, the lakeside case crept back in. Something about it—elusive, undefined—kept tugging at him. After twenty years chasing petty thieves, was he just burned out, craving a challenge with weight? Or did this case stir something deeper? He’d grown up here, worked here his whole life; a mystery this old, rooted this close, was bound to unsettle him.

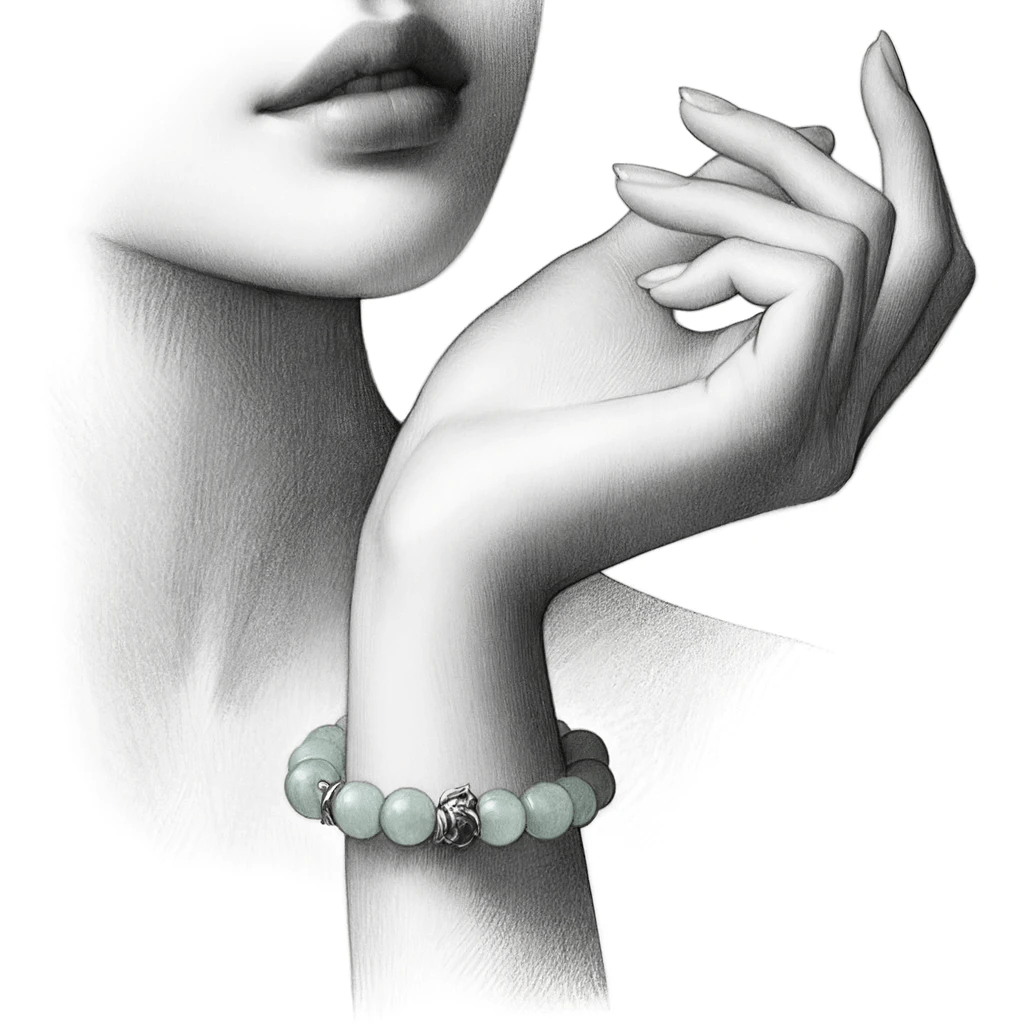

Back at his desk, he found himself staring at the case file again. Those five sheets of notes—he could recite them blind. As evidence, they were flimsy, useless. But the two pencil sketches? They were different.

Whoever drew them had an artist’s eye, a steady hand. The MCC officer, the Political Commissar who’d led the initial probe, seemed the likely artist—assuming he wasn’t also the typist. That felt improbable; MCC brass didn’t hunch over typewriters, and most wouldn’t know how.

Then there was the hand in one sketch. It lingered in his mind, unfinished yet deliberate.

If the sketch was included in the case file as part of the evidence, why was it not a sketch of the victim, but only the hand? That didn’t add up. At least in the case of the other sketch, one could reason that it was included because it provided a graphic description of the location where the body was found. But that same logic did not apply to the hand sketch.

Was it all just chance? After all, it happened at the height of the Cultural Revolution—a time when chaos reigned. No one was really in charge back then. Maybe there was a doodle lying around, and somehow, in the madness of those days, it got mixed up with the case file. Possible, but unlikely.

No, the coincidence stretched too far. Two sketches in a murder file, one a precise rendering of the crime scene—randomness couldn’t explain that. There had to be intent behind their inclusion. But why?

He had a feeling that the key to the case lay in those two sketches. He needed to find out who made them.

Then he remembered Zhou, a retired administrative officer from the Comprehensive Division. Forty years in the bureau, retired just a few years ago—if anyone knew its buried secrets, it was him.

5

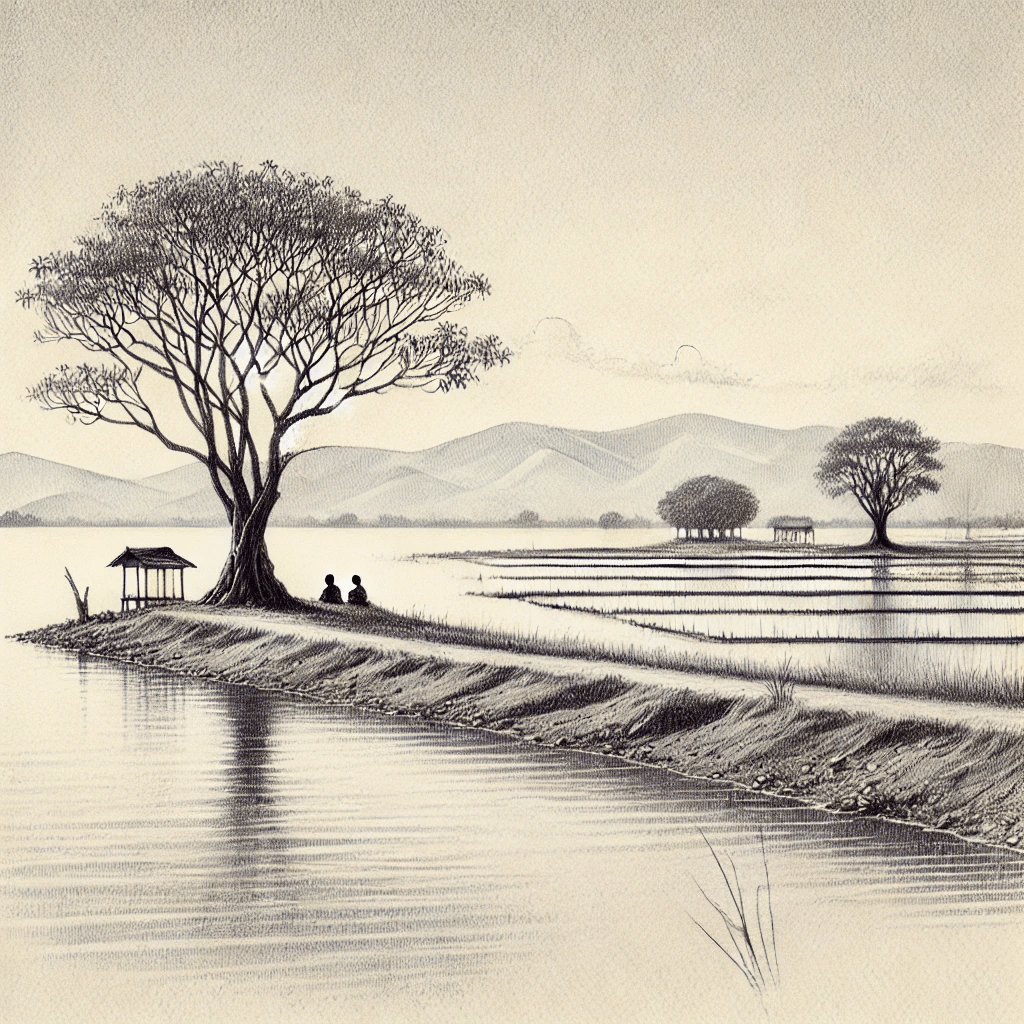

He wasn’t familiar with this stretch of the lake and was wondering if he’d misread the directions when Zhou emerged from behind an old Sacred Fig tree. The suddenness jolted him.

“Did I spook you, officer?” the old man said, grinning.

“Oh—hi,” he stammered, caught off guard.

“Make yourself at home,” Zhou said, easing back into his spot by the water, though he left his fishing rod untouched. “Thermos is there—pour yourself some tea.”

He sank onto the ground, filled a cup, and joined Zhou in silence. Before them stretched the lake’s vast shimmer beneath the afternoon sky, distant mountains faint on the horizon.

“When you called yesterday,” Zhou began, “I thought, ‘Never figured someone’d dig up that case again.’ And what better place to talk than here?”

“So you knew about it?” he asked.

“I knew it came up back then,” Zhou said. “Worked on briefly, sure. But a file? That it survived—now that’s a shock.”

“You were in the Comprehensive Division when the MCC took over,” he said after a pause. “What was it like under them?”

Zhou didn’t reply at first. The silence stretched between them.

“On the phone,” Zhou said at last, “you asked about the MCC guy on this case. Been so long—guess it’s fine to talk now. He was the Political Commissar, ran the day-to-day. Not the battalion commander.”

“Was he the only one who looked into it?”

“He handled it, but ‘investigation’ is generous. ’68 was madness—senior officers ousted or branded enemies, manpower thin. We were scared, too. Crimes went dark, or if they surfaced, no one dug deep. Revolution trumped everything.”

“His signature’s on some of the papers,” he noted.

“Odd, right?” Zhou said. “The Commissar took an interest—stood out back then, busy as he was. What was he like? Quiet, bookish type. Wrote well, read a lot. Not every soldier could.”

“Could he draw?” he pressed. “Like, pictures?”

“Oh, yeah,” Zhou said, nodding. “Good at it, too—helped the lads with posters for events. Come to think of it, he wasn’t like the rest.”

“What happened to him after the MCC folded?”

“Lasted two, maybe three years—then Revolutionary Committees took over, civilian outfits. Some MCC folks left, some went back to the army. Him? He stayed on as a civilian. Heard he died a few years back.”

“Any family left?”

“Had a wife—saw her once or twice under the MCC. No kids, I don’t think.”

A wind kicked up, sharp and growing. They rose to leave.

“One last thing,” he said, hesitating. “What happened to the body after they found it?”

“Brought in, then gone in a day or two,” Zhou replied. “No forensics—nobody to do it. Cremation wasn’t big then.”

“Buried where?”

Zhou chuckled. “Where we dumped all the unclaimed. You know the old execution ground west of town, in the foothills? For criminals back in the day?”

“Think so,” he said, sheepish at the obvious.

“You do. That’s where—convicts and strays alike.”

As they parted, Zhou turned. “I knew your late father,” he said, pausing. “Good man. You need me, I’m here.”

6

The woman across from him, old but sturdy, embodied the northern villages of Shanxi or Hebei. Her thick accent colored her words, and her rough hands, offering tea, betrayed a rural life. Warm and unpretentious, she spoke slowly, her manner simple. He pegged her at sixty-five.

“Getting old,” she said, smiling as she thumped her knees with startling force. “Hands and feet aren’t what they used to be.”

He’d told her he was from the bureau, here on personal business. She’d welcomed him without a flicker of doubt, eager for company.

“Been here thirty years,” she said. “Even after my old man passed, they let me keep this place. Grateful to the mining company leaders… He was in charge there till he retired. A far cry from the military days—garrison life with army families, then the public safety bureau in this county, and finally the mines. Company’s struggling now, I hear. Young folks lost jobs, headed to the city. It’s quiet these days.”

The mine lay five kilometers from the county center. The decline was palpable—shuttered factories trailing a shuttered mine. People had stopped trying to decode the shifts, let alone predict what came next.

He set the case file on the small tea table and slid out the hand sketch.

“Something I’d like you to see,” he said.

She took it, squinting. “Not a photo, huh? A hand—drawn.” She handed it back. “Eyes aren’t sharp anymore.”

“Ever seen anything like it?” he asked, laying it down.

Her head dipped. The knee-thumping stopped. Silence swallowed her earlier cheer.

“My old man used to sketch hands like that,” she said softly. “Loved it. I’d catch him at it sometimes, by chance. He didn’t like me prying, so I stayed quiet. Just a country woman, an army wife, you know?”

He waited as she steadied herself. “Might he have kept any drawings?”

“Left some things behind,” she said. “Kept them, but never figured what for.”

“Could I take a look?” he asked, treading carefully.

She didn’t resist.

“No kids, see,” she said as they moved to the bedroom. “I’ll be gone someday. Who’ll handle this then?”

A suitcase perched atop an old wardrobe. She pointed, then shuffled back to the living room, leaving him alone.

He eased the suitcase down—a faded brown relic, the kind cluttering homes decades ago. Light and sagging, its lock popped open with a tug, never meant to keep secrets.

A thin stack of papers, tied with string, caught his eye first. Beneath a blank sheet lay a pencil sketch: a hand with a jade bangle circling the wrist, eerily like the case file’s. Another page, another hand. His breath snagged.

He didn’t count them—half a dozen, maybe more—his pulse too quick to care.

Beside the papers sat a black jewelry case, velvet worn dull. Inside gleamed a pale green jade bangle, stunning even to his untrained eye. He stared, rooted.

Setting it aside, he spotted a brown office envelope, weathered and stiff. He pressed it with his thumb—light, shapeless, not paper or fiber. Something soft, like hair.

A cold wave surged through him. Nausea coiled in his gut. He couldn’t touch more.

7

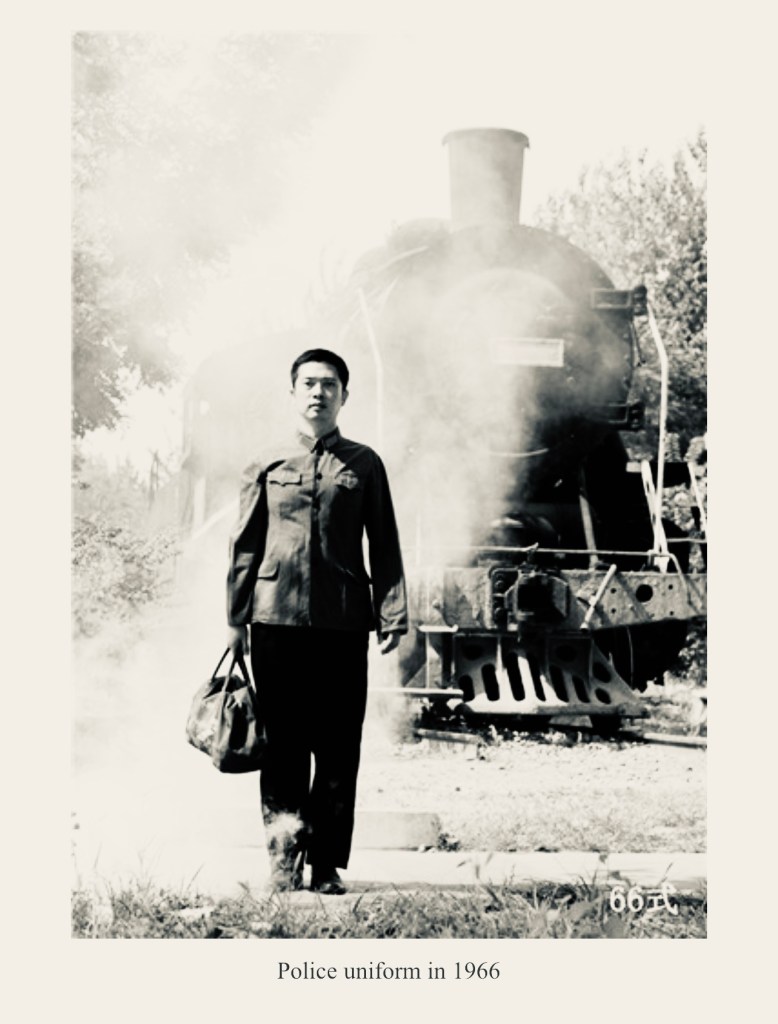

Days had passed since his visit to the old woman at the mining site, and for the first time, he felt adrift. Something inside him had come unmoored. Focus eluded him; distractions ambushed him. He lingered longer in his cubicle, pulling away from colleagues, his mind often elsewhere—a change they quickly noticed.

For a while, he immersed himself in reading about the evolution of police uniforms in China. The 1966 style particularly fascinated him. What struck him most was how indistinguishable it was from army uniforms. To his surprise, he wasn’t just drawn to the simplicity of the design; he felt an unexpected connection to it. Then he stumbled upon an old photograph that captivated him.

And then there was the music. In the neighborhood where he grew up, there used to be a tire factory behind his house. Every day at noon, the factory’s loudspeakers would broadcast music—two distinct genres. One was revolutionary songs, loud and exhilarating, reminiscent of marching bands. The other was nostalgic, sorrowful, and lonesome—a variant of Tibetan melodies. As a child, he always looked forward to the broadcast. After all, there wasn’t much else to do at the time.

Lately, he also found himself drawn to jewelry. Occasionally, when his wife sat at the dresser in the morning to put on her makeup, he would pause and watch her—something he had never done before.

“What’s up, old man?” she teased. “First time seeing me here?”

“Got any jade bangles?” he asked one day.

“Several,” she said. “Why?”

“Nothing,” he mumbled, dodging. “Just wondering.”

On duty near the local temple, he spotted a jewelry store by the gate. Impulse pulled him inside. He quizzed the clerk, but the answers muddied more than they cleared.

8

He returned to the lakefront where he had met Old Zhou, hoping to see the old man again. But Zhou was gone. There was no fishing rod, no bamboo basket bobbing in the shallows. Disappointment sank into him. After a while, he wandered along the shore.

It still amazed him that a pool of lake water could appear so deceptively gentle and peaceful, pure and innocent, like someone without a care in the world. Its seeming tranquility made one think it had never hidden secrets, never swallowed lives, and never stirred up waves. The lake in his earliest memories had always been like this—calm and serene. But on closer thought, that could only be one of its faces. This lake had not always been so peaceful. There had been death, floating corpses, and silent witnesses to murder.

What was that saying people often used? ‘Tempestuous waves will eventually cleanse all filth,’ or perhaps ‘The great wave sifts the sand’—or was it ‘Water purifies everything’? Whatever it was, as he gazed at the lake’s glassy surface now, it was hard to imagine that such a peaceful place had once borne witness to unspeakable evil.

When all is said and done, isn’t life just like this? Beauty and ugliness coexist, heaven and hell intertwined—how could anything ever be perfect? He never imagined that, after years as a police officer, he would one day find himself pondering such philosophical questions here. The thought made him chuckle.

Whatever the case, now that he was past forty, one thing seemed certain—he wasn’t leaving this place. Whether by fate or by choice, this was where he would live out his days. And he had no regrets. This had always been his home, and always would be.

Who knows? Maybe one day, when he retires, he’ll pick up a fishing rod and a pot of tea and, just like Old Zhou, come out here to sit by the lake, casting his line in quiet solitude.