1. The Day Literacy Disappeared

One fine morning, as the sun began to rise over Japan, an unprecedented horror struck the nation. The entire writing system, evolved meticulously over centuries since the 5th-6th CE, had vanished. All printed and handwritten books, all online texts, and every visual form of writing—from subtitles in anime to road signs—were gone. More disturbingly, the very ability to read and write had inexplicably evaporated from the minds of the people. Professors, writers, students, and government officials alike woke up to find themselves functionally illiterate.

Yet, life went on. People conversed as usual, the news was broadcast orally, and parliamentary debates in the National Diet continued unabated. It was as if the nation had declared an impromptu “National No Reading Day.” But unlike a holiday, this day stretched into another and another, and soon, what began as an anomaly became the new normal. Literacy was no longer part of Japanese life, but the spoken language flourished uninterrupted.

2. A Nation Without Written Words

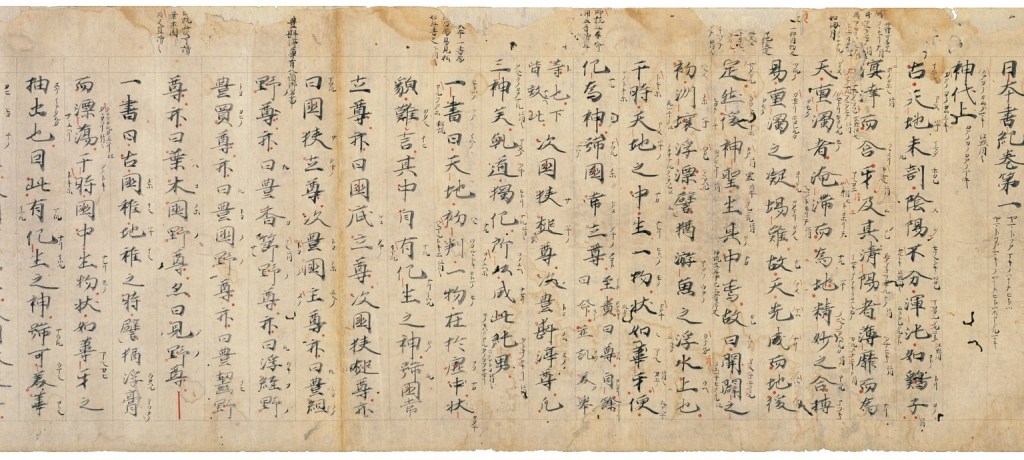

Weeks turned into months, and the absence of writing became a way of life. Over time, the collective memory of Japan’s intricate writing systems—kanji, hiragana, and katakana—faded. Japan transformed into a society of talkers. The beauty of literary classics like the Kojiki and The Tale of Genji lived on only in oral recitations.

When a Chinese tourist, visiting Japan, produced a copy of the Kojiki written in kanji, not a single Japanese person, not even the nation’s top linguists and literary professors, could decipher it.

However, when the knowledgable tourist read it aloud following the transliteration notes, the Japanese understood every word perfectly, marveling at the sound of their own language as if hearing it anew.

3. A Call for Help

Alarmed by this national loss, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency. After much discussion—all oral, of course—the government resolved to seek international assistance. A delegation was dispatched to the University of Washington (UW) in the United States, renowned for its linguistics department, to request help in creating a new writing system for the nation.

Upon arrival, the delegation explained their plight to the UW linguists, who, though sympathetic, were overwhelmed with their own projects and slightly uninspired. In their haste (and perhaps laziness), they proposed a solution: “Why not use the English alphabet? And while we’re at it, let’s toss in a few diacritical marks like the French use—graves, aigus, and the occasional trema. Oh, and let’s add a unique symbol for your Japanese ‘r’ sound, like an ‘r’ with a dot on top.”

The resulting system was christened “Beikokuji” (or 米国字 before the disaster struck, meaning “American Characters”), a nod to its foreign origins.

4. The Beikokuji Revolution

Upon returning to Japan, the delegation introduced Beikokuji to the government. A national decree was issued, requiring all school-age children and adults to attend classes to learn the new system. Despite initial resistance, the Japanese—known for their resilience and adaptability—embraced the challenge. With the blessings of Shinto gods, Buddhist deities, and their own indomitable spirit, the nation regained its ability to write within an astonishingly short period.

5. A Nation Reborn

With their newfound literacy, Japan declared a national holiday to celebrate the rebirth of its written language. On this day, the Prime Minister addressed the nation on television, using the new Beikokuji system:

“Minasankon’nichiwa! Minasan mo gozonji no tōri, wagakuni wa saikin ōkina sainan ni mimawa remashita. Watashitachi wa furui moji taikei o ushinaimashita. Shikashi, wagakuni wa kichi ni tomi, kaifuku-ryoku ga ari, kokumin wa kesshite kibō o sutemasendeshita. Kyō, wagakuni ga atarashī moji taikeidearu Beikokuji no dōnyū o iwau naka, oiwai mōshiagemasu!”

As part of the celebration, the government organized an unprecedented feast. Sushi and sashimi of the highest quality were distributed freely to all citizens and visitors alike. The offerings included delicacies such as katsuo, sake, maguro, ahi, engawa, saba, and hamachi, ensuring that everyone could partake in the joy of the occasion. Foreigners visiting Japan during this time marveled at the generosity and culinary excellence, feeling privileged to witness this moment of cultural rebirth.

6. The World Reacts

Among the foreigners visiting Japan after the introduction of Beikokuji, the happiest were those whose native writing systems already used Roman characters. For example, an English speaker could easily read the Prime Minister’s address aloud, even without understanding its meaning: “Minasankon’nichiwa! Minasan mo gozonji no tōri…”

Navigating Japan became significantly easier for Western tourists. If an English speaker needed directions to Ueno Station, they could simply say, “I need to go to U-e no eki,” and be understood. Similarly, asking for the best place to see cherry blossoms required only a simple question: “Where can I find the finest sakura?”

The Chinese, however, faced new challenges. When they asked for directions using the original Chinese pronunciation of 上野站 (“shang-ye-zhan”), locals were baffled. They understood “Ueno” but not “shang-ye,” they knew what an eki is, but had no idea what “zhan” meant. Likewise, while “sakura” was immediately recognized, 桜花 (“ying-hua”) left the locals puzzled.

7. The Lesson: Spoken vs. Written Language

One clear lesson from this story is the importance of distinguishing between the spoken and written forms of a language. Many people, when thinking about “language,” conflate it with its written representation. They think of the words they see in books, newspapers, or on screens, rather than the spoken words that carry the true essence of communication.

Even scholars are not immune to this conflation. A professor in China once argued with me that the Chinese word “shan” (mountain) has two meanings because the character 山 has “mountain” as its linguistic meaning, and also it looks like a mountain, in contrast, the English word “mountain” has only one meaning—a pile of rocks and dirt. What this professor fails to see is that, if I say to both him and an illiterate farmer, “He is from the mountains,” both the farmer and the professor understand the same thing. Of course, the professor can then say, “Ha, but I know which written symbol is shan, and he does not.” This is a perfect example of ignorance about the distinction I’m trying to stress: whatever he associates with the character is not part of the language; it is something outside language.

Misunderstandings about written language also breed misplaced patriotism. It’s not uncommon to hear claims like, “The Japanese stole our words because they couldn’t think of their own.” This perspective ignores the historical reality that cultures have always borrowed from one another. More importantly, it overlooks the fact that the Japanese adapted Chinese characters to record Japanese sounds. This is why a Japanese speaker reads 桜花 as “sakura,” not “ying-hua,” and he reads 米国 as “beikoku,” not “mi-guo.”

Recognizing the distinction between spoken and written language can help dispel such misconceptions. Writing is a tool for representing language, but it is not the language itself. Nations should remember that while scripts and symbols may change, the spoken word carries the heart of communication and culture.