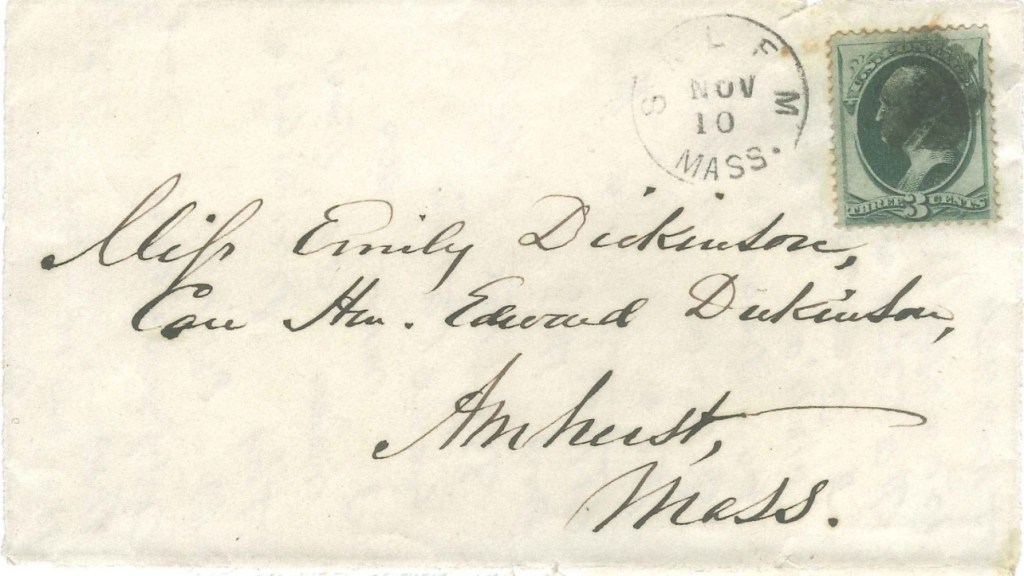

This is my letter to the world

That never wrote to me—

The simple news that Nature told

With tender Majesty.

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

Private Message, or Public Post?

In ancient times—that is, from the birth of Jesus Christ up until about the year 2000—there was no internet and no smartphones. If you wanted to tell your cousin something, you had to write him a letter and take it to the post office. If you were far from home and your parents were worried you’d been abducted by people without smartphones, you’d head to the post office and send them a letter, telling them: “I know, I know—you’ve told me a thousand times already: ‘At home, you rely on your parents; away, you rely on friends.’”

Nowadays, everything is digital. With the internet and smartphones, asking someone to write you a letter no longer involves pen and paper. Instead, you say, “DM me!” (short for ‘Direct Message me’).”It’s just a fancy way of saying, “Write me a letter.’ But this practice has been around for ages. Back in Shakespeare’s time, people would add notes like “post hast” or “giue theis with spede” on the envelopes of private letters, urging messengers to hurry.

OK, guys, my English isn’t wrong here! People back in Shakespeare’s day misspelled words all the time. Honestly, how did they get away with that in front of their teachers? If you don’t believe me, look it up online.

In our country the Middle Kingdom in ancient times, if you wanted a letter delivered quickly, you’d write “急急如律令!” on the envelope (“Swiftly, as if by decree!”). If it was extra urgent, you’d add: “太上老君急急如律令!” (“Swiftly, as if by decree of His Majesty Laotzi in Heaven!”). Otherwise, off with your head—your skull hung at the city gate for crows to peck at.

Usually, after writing letters to your cousin and parents, you’d feel like something was still amiss—like there were more letters waiting to be written. So, you’d dip your fountain pen into the inkwell, stare into space like a bird in your backyard tilting its head sideways to study you, and start writing. But these letters weren’t addressed to anyone in particular. I mean, when you wrote them, you weren’t thinking of anyone specific. It’s like being hungry and heading out to find food without knowing exactly what you want—just that you need to eat. You need to write, but you don’t know who the letter is for.

These letters would pile up in your drawer cuz you never took ‘em to the post office, and you never took ‘em to the post office cuz mailing a letter requires a recipient, an address, and a stamp. But you were just a young person, and you only had the addresses of your cousin and your parents. You didn’t know many people, and you spent half your time living in a world populated by people without addresses. So, you’d sit with your chin in your hand, writing letters that would never be sent, letting them stack up in your drawer.

Today, that drawer exists on WeChat. You type a message on your phone, save it for later, and post it when you’re feeling happy—or when you’re feeling down. This is how posts are born—the things everyone shares on WeChat Moments today.

When you publish a post on Moments, you’re not thinking about any specific recipient. In your mind, your WeChat Moments are the world, and posting there is like sending a message to everyone in it. This thought—that the whole world is hearing your voice—fills you with satisfaction.

But almost immediately, frustration creeps in: “People are definitely going to misunderstand me! Oh, it’s terrible! So tragic! No one understands me. Understanding is so hard.”

Thinking about how your letter to the world is being so tragically misunderstood makes you sad. You grab a tissue to wipe your nose and dab at the tears welling up at the corners of your eyes.

“To My Dear Cousin Alexander”

My first letter—my first “real” letter—was one I wrote, finished, and walked all the way to the post office to send. It was addressed to my cousin in Guangzhou, a train ride of perhaps two days away.

I was just starting middle school then, no older than 14. Before that, I’d written things, but only school assignments handed to teachers. This letter was different. For one, it was written to a real person. For another, my cousin wasn’t like my parents or teachers; he didn’t live with us, as my parents and siblings did.

Plus, he lived far away, in a big, famous city. It was also a proper letter—placed in an envelope bought from a store and sealed with a stamp featuring either a sickle and hammer or some famous person. You’d fold the letter, slip it into the envelope, and seal it with glue provided by the post office staff.

But that wasn’t the end of it. You had to go to the post office to buy a stamp. And stamps cost pocket money—the allowance you’d been saving for sweet treats. Once you had the stamp, you’d lick it or dip it in rice paste to stick it onto the envelope. Then you’d walk up to the deep green mailbox, pull down the lid, and let the letter slide in.

But even then, you’d worry: Did the letter fall properly into the mailbox? Could it have gotten stuck in a crack and never been collected by the postal worker? And if that happened, my cousin would never get to see the letter I wrote to him. How would I explain myself if I ever saw him again? So you began to fret over not hearing the thud of the letter falling into the mailbox, and you looked for a clean spot by the curb near the box to sit and fret over it.

That’s how I sent my first “big boy” letter—my first letter to the world. I felt incredibly proud, pacing back and forth with a solemn expression, thinking this was how someone who’d just sent a letter at the post office should behave—like Mom and Pop when discussing serious matters. From that moment on, I considered myself a big boy.

I don’t remember what I wrote in that letter, but if I had to guess, it might have gone something like this. At the time, I had a collection of Alexander Pushkin’s poetry, so it’s very possible that my letter began with these words:

“Dear Cousin Alexander Alexandrovich,

…I imagine us as Cossack cavalry, riding on horseback and swinging our sabers. If life deceives you, don’t be sad… brighter days will come. Yours sincerely, Cousin Sergey Sergeyevich.”

But now that I think about it, I also had on hand a copy of 《古文观止》(Selections of Refined Ancient Chinese Prose), so the letter might also have been written in a Classical Chinese style, like this:

“表弟某足下。敬启者 … 自夏 … 不通闻问,经夏涉冬 … 吾侪 … 已亦乎,哀哉 … 日月淹忽 … 表兄某,顿首。”

“To my esteemed cousin, greetings.

Good Sir, … since summer, we have not exchanged news. Summer has turned to winter… we, men of our order, alas… how swiftly the days and months slip by…

From your cousin, humbly bowing.”

That said, my cousin is Hakka, Mr. Chow Yun-fat the Hong Kong actor is Hakka, and I’m half Hakka, so it’s also possible that the letter was written in Hakka dialect. It might have looked something like this:

“表汰老汰妮吼 … 妮係讹呵頭好个朋友,有幾下個知心即罅啊。細子頭佮意提著矺年錢。逐日攏愛䀴書正會進步。”

Letter Paper from Kashgar

As you grow older, you write more letters and send more of them. But for me, the strange excitement of writing and mailing letters never diminished.

During my first year of college, I became close friends with a classmate from Kashgar. We were inseparable, always studying together. Among his few possessions were some decorated letter papers—traditional in style, with elegant designs and exquisite texture. They reminded me of the Xuan paper of Zhejiang’s Fuchun River, the Ten Bamboo Studio Letter Paper of the Ming Dynasty, and The Beijing Letter Paper Collection compiled by Lu Xun.

Such beautiful things I had never seen before. Over the years, I’ve often wondered how such refined stationery could come from a remote place like Kashgar.

My Kashgar friend generously gave me a pack of his letter paper, and I was overjoyed. Just looking at it filled me with happiness. I couldn’t resist taking it out, laying it gently on my desk, and admiring the stunning illustrations on the cover. The delicate sheets beneath were sheer joy—thin as dreams. This wasn’t mere stationery; it was threads of cloud, woven to craft a dream.

Each time I spread a sheet before me, I felt compelled to write something on it. Even a few words would do. If not words, at least I could breathe on it. Or perhaps whisper a secret to it. Or weave a dream into it. Every time I placed a sheet before me and picked up my pen, my hand would tremble, my heart would race, and I could hear its pounding echoing in the room.

Had I lived in the Middle Ages, when people believed in angels, I would have used this paper to write to one. In the absence of angels, a mere mortal would do. Once, I used this precious paper to write two letters to a high school classmate—a girl who was studying in another city at the time. I didn’t know her well; she was practically a stranger to me. But I hoped that when she received my letters and unfolded the paper, she would feel what I felt when I wrote them. But who’s to say?

When I wrote, I laid more than words on that paper. As my pen glided over it, I laid down my dreams. A slightly heavier breath or a minor tremor in my hand felt like it might disturb them—like it might wake them. My dreams would then rise from the paper, fluttering like butterflies into the still and transparent air. And I, with dreamy eyes, would hold my breath in silence.

An Unexpected Postcard

One day, after graduating college and working in the mountains as a teacher for a geology team, a mailman brought a postcard to the school office. It was for me.

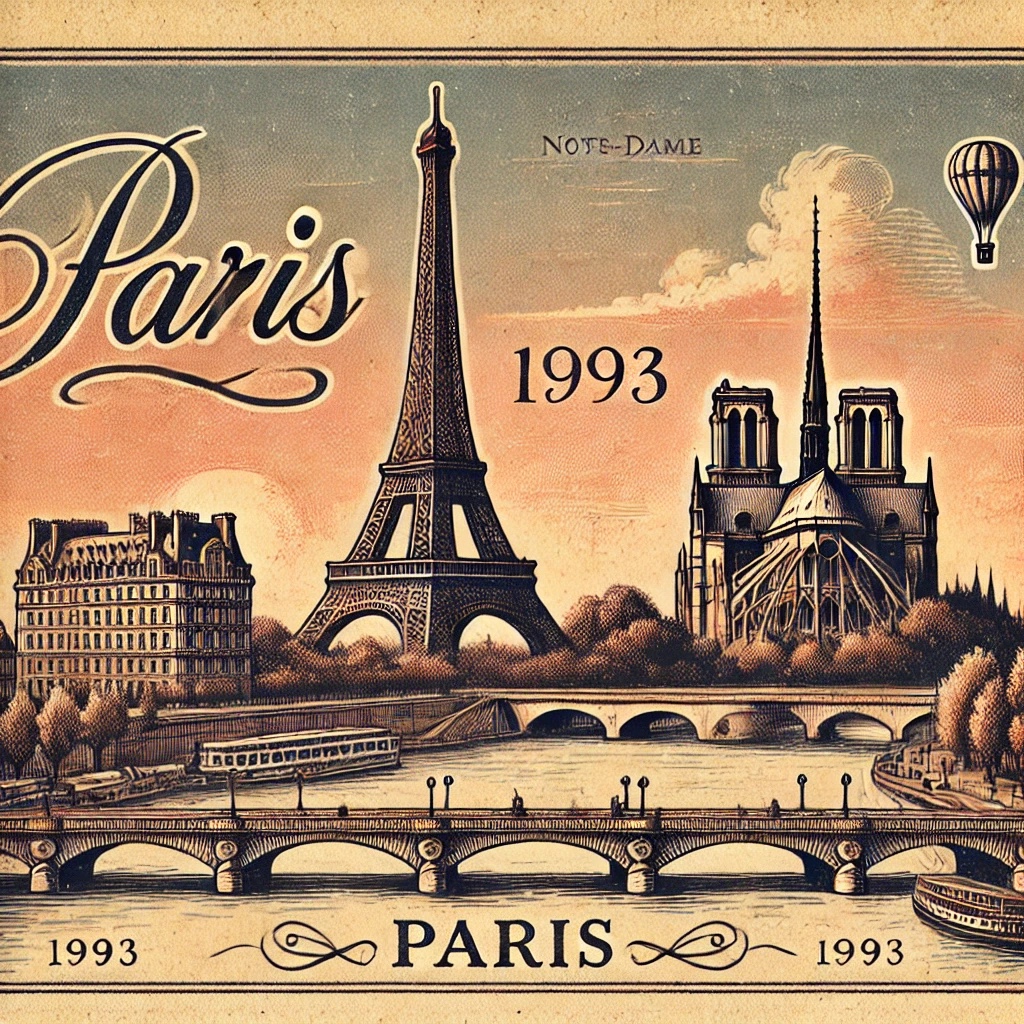

In those days, I rarely received letters, let alone postcards. And this one was from France! It read, “Paris, 1993.”

The sender was a university classmate I didn’t know well. Why would this person send me a postcard from France? I concluded that he must have sent one to everyone in our class. As I later discovered, I was right.

Even with this inkling in the back of my mind, I still felt a thrill—someone had sent me a postcard from far away, from Paris!

“Dear Jane”

There was a time in my life when I wrote letters most frequently. This was shortly after I landed my first teaching job at a university. It all started with a girl I met briefly during the spring semester. She was an undergraduate majoring in biology, while I was a graduate student at the same university.

After graduation, she found a job and left campus. From that autumn onward, I began writing letters to her. She seldom replied, but I kept writing. Over time, it became a habit. Most of the time, I think I was talking to myself—or to someone who existed only in my imagination. Let’s call her “Jane,” short for “Jane Doe.”

To this day, I still remember some lines from those letters. One began like this:

“Dear Jane,

In these winter days, I sometimes read, sometimes play the guitar, but most of the time, I think of you.”

Come to think of it, this must be how I looked in those days🤣🤣🤣:

Another letter went like this:

“Dear Jane,

Today, I passed by your old dormitory; the building hasn’t changed, but the trees have turned green again, just as they did this time last year. But you’re no longer here…”

Here’s another one:

“Dear Jane,

Yesterday, I went walking in the fields near the school. I saw wild geese flying overhead, looking as though they were heading south for the winter. I hope that as they approach Shanghai, they take a detour—otherwise, they might be caught by hunters, sold to high-end restaurants, and end up as delicacies on the tables of that city’s twisted elites and nouveau riche.”

In yet another letter, I described what I saw during a solitary walk:

“Dear Jane,

Today, I walked far into the fields beyond the school, to a place where there were almost no signs of human life. All around me were harvested fields, and beyond them, more fields and barren land. By noon, I stumbled upon a spot that looked so surreal it left me speechless. Who knows how long I stood there, stunned, as though caught in a dream?”

And in another, I wrote of a dream:

“Dear Jane,

Last night, I had the strangest dream. I was walking, and a cool breeze swept in from afar. It led me to a lake. Beneath low, gray clouds, the shore stretched gently with pale brown and white pebbles, meeting crystal-clear water. Overcome with excitement, I ran down the sandy slope like a child, oblivious to what lay ahead. Reaching the water, I lifted my head and froze, as if struck by an invisible force. Quietly before me was an oval-shaped lake, surrounded by green pines, with a low gray sky overhead. A faint sorrow hung in the air.”

Brother in the Middle

Once, during that winter, an incident occurred at the school involving a student who had been expelled. Someone was needed to handle the case, and I was sent on a trip to deal with it. This trip gave me the opportunity to visit Jane, as her city was on my route.

After completing the task, I visited her on my way back.

After that, I went to see her several more times. When I visited, she would come to the hostel to see me. She’d sit by the bed, and we’d talk, or we’d go for a walk. To me, she felt like those beautifully decorated writing papers I had years ago—so soft, so delicate, and carrying a faint, enchanting scent. I wanted to touch her, but didn’t know how to begin. In the end, I’d just say something like, “Your hair smells nice,” and then we’d part ways. Before leaving, she would hang her music player around my neck.

Walking back to the hostel, I would think about her the whole way, listening to the songs she loved.

Our time together was always short. We both knew that if all we did was take walks, it would always just remain that way—just walking. But I didn’t have the courage to take the first step.

When I was in graduate school, they often posted philosophical stories on bulletin boards to educate new students about what philosophy was and how it differed from other disciplines. One such story went like this:

A boy and a girl went on a date. They always sat on a park bench, awkwardly saying little and doing nothing. Time passed, but they remained stuck, unsure how to break the ice. One evening, sitting as usual on the bench, the boy asked, “Do you have a younger brother?”

“No,” the girl replied.

“If you did,” he said, “do you think he’d like me?”

This hypothetical question broke the ice, sparking their imagination and prompting action.

The story on the bulletin board was meant to educate new students, emphasizing that philosophical questions are essentially “What if…?” questions. You could, for example, ask:

“What if Confucius had fallen into a pond and drowned at the age of three? What would Chinese culture have become?” or:

“What if Bodhidharma’s ship had been blown off course to Java by a strong wind and never landed in Guangzhou? What would Chinese Buddhism look like today?” Or,

“What if, in ancient times, when Chinese people first began speaking, they called eating ‘sleeping,’ sleeping ‘eating,’ fathers ‘mothers,’ and brothers ‘sisters’? What would Chinese sound like now?” and for a fun one and close to home:

“What if Steve Jobs and Joan Baez had become a couple and he ended up playing drums for her band? Would there still be iPhones?”

Inspired by such “What if?” scenarios, one night, while Jane and I were walking on a medical school campus, I tried my own version. I said, “They say if someone’s mischievous, there’s a bump on the back of their head. Let me check if you have it.”

She stopped walking, tilted her head toward me, and let me touch the back of her head to check for the bump.

Little boys and girls: don’t just walk past the bulletin board—read it!

This back-and-forth travel led to an unexpected outcome: I became friends with her brother. We quickly grew close.

He was quiet, kind, and shy, with a deep loyalty to his sister. She treated him like a mother would her child. One of our favorite activities was playing board games. We’d lie on the bed with the game spread out in front of us and play for hours.

At night, he’d sleep in their parents’ room so I could use his. After the lights went out, I’d end up in her room. I was certain he knew what went on between his sister and me, but he never said a word, nor did he show any reaction.

The next morning, we’d sit at the kitchen table, eating breakfast and chatting as if everything were perfectly normal. And indeed, it was normal. Jane was my lover, and her brother felt like my own. We were like family.

Life could have gone on this way forever. Jane as my lover, her brother in the middle, the three of us perfectly content with this arrangement.

A Postcard for the Brother

Time apart always feels long in the moment. Looking back, it’s nothing but an instant, maybe even shorter.

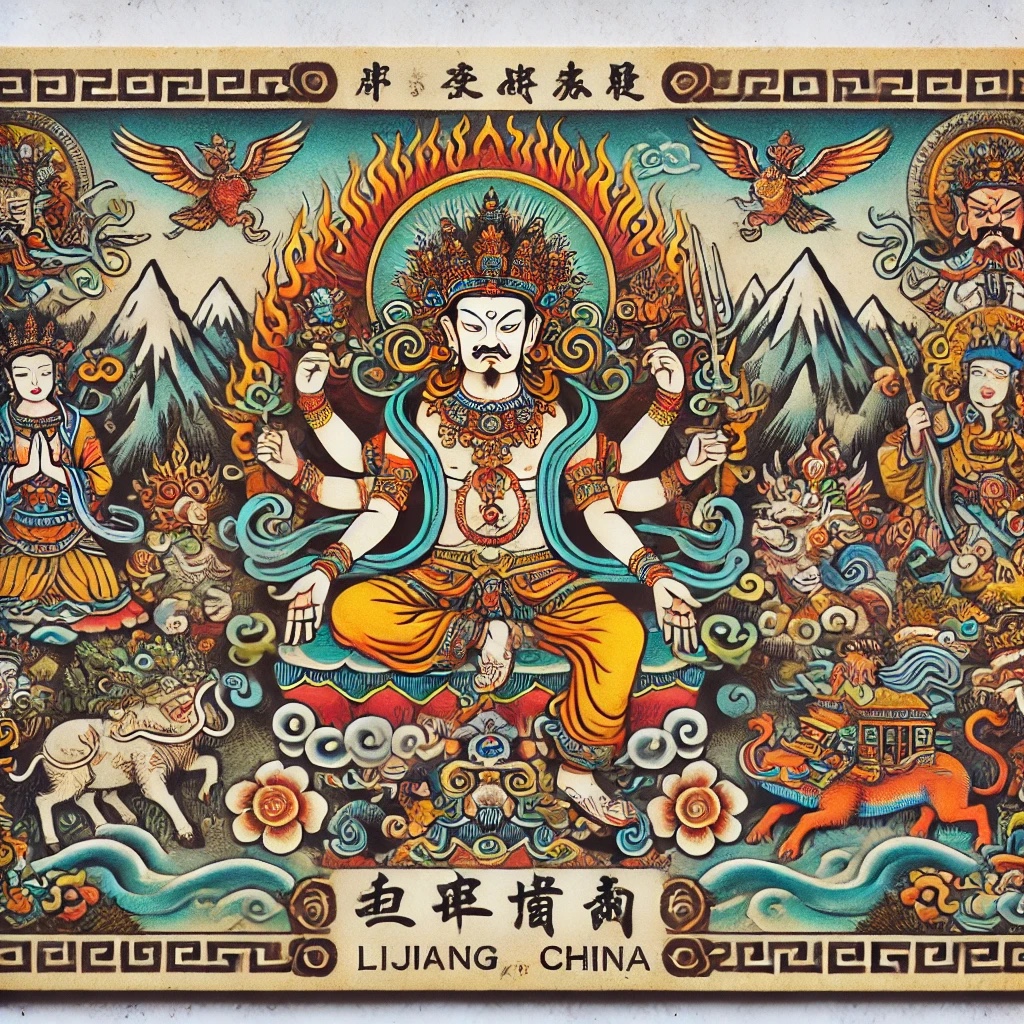

Years later, we met again in my hometown of Lijiang.

Our driver for this reunion was a young Naxi man, earning money before his wedding. We hired him and his Santana for three days. “How much?” We asked. “You name the price,” he said.

During those three days, we visited Tiger Leaping Gorge, Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, and Lugu Lake. On the way to Lugu Lake, we detoured to Shigu Town by the Jinsha River.

At Shigu, we saw the Red Army crossing site, marveling at the incredible feats of the Red Army back then. Walking through town, I spotted a quote of Chairman Mao’s on a wall:

“All reactionaries are the same: if you don’t knock them down, they won’t fall.”

It struck me as something that could be printed on a postcard.

The night before leaving Lijiang, we rested at a small inn. Among the staff was a young white foreigner with ginger-colored hair. Maybe he wasn’t staff—perhaps just a guest. He looked like someone struggling with Chinese food but sticking around in China anyway.

As he was served a flatbread to eat, we started chatting. He said his name was Luke, from England. A perfectly ordinary man, he didn’t have much interesting to say. Jane stayed silent, watching from the side.

On our last day in Lijiang, we decided to send her brother a gift. Browsing souvenir shops, we settled on a postcard. I chose one with Jane’s approval.

It was the most beautiful card I’d ever held. As soon as I picked up a pen, these words flowed naturally:

我来游麗江,水秀山青;又听纳西古樂,鏗鏘有韻致。鸿雁送你明信片一枚,上有牛头马面,教你做个噩夢。爱你的。姐姐。还有那边头发乱乱的那个。

“I traveled to Lijiang, with its beautiful waters and green mountains; listened to ancient Naxi music, resonant and melodious. A wild goose delivers this postcard to you, with a bull-headed ghost and a horse-faced demon on it, to give you a nightmare. With love, your sister. And the messy-haired one over there.”

As I signed it, I truly felt like I was his sister writing to her beloved brother, far away but deeply caring for us.

Emily Dickinson

Years later, during my time in Wisconsin, I eventually earned my doctorate and began teaching at a state university. The town I lived in didn’t have a bookstore, and the nearest one was a Barnes & Noble about twenty miles away. Wanting a change, I decided to explore another bookstore in a nearby town, which I’ll call Durand.

The new bookstore was in a small shopping center, surrounded by soybean fields. Nearby was the state prison, or as they called it, the correctional center. Signs along the road warned: “Prison Zone.”

At the time, I had never heard of Emily Dickinson. I wasn’t familiar with her name or her work. But that day, as I browsed the literature section, her name caught my eye. I picked up a book and opened it.

These lines, familiar to millions around the world, leapt off the page:

This is my letter to the world

That never wrote to me—

The simple news that Nature told

With tender Majesty.

From that day forward, that small book never left my side. Dickinson’s name became part of my world. Whenever I drove through western Massachusetts, past the tree-covered hills, I thought of her. I would say to myself:

“Not far from here is Amherst, the town where this little woman spent her entire life, never traveling anywhere else in the world. Yet what she left behind for humanity was an entire universe. These hills and forests must be what she saw with her poet’s eyes as she waited for the world to write back to her.”

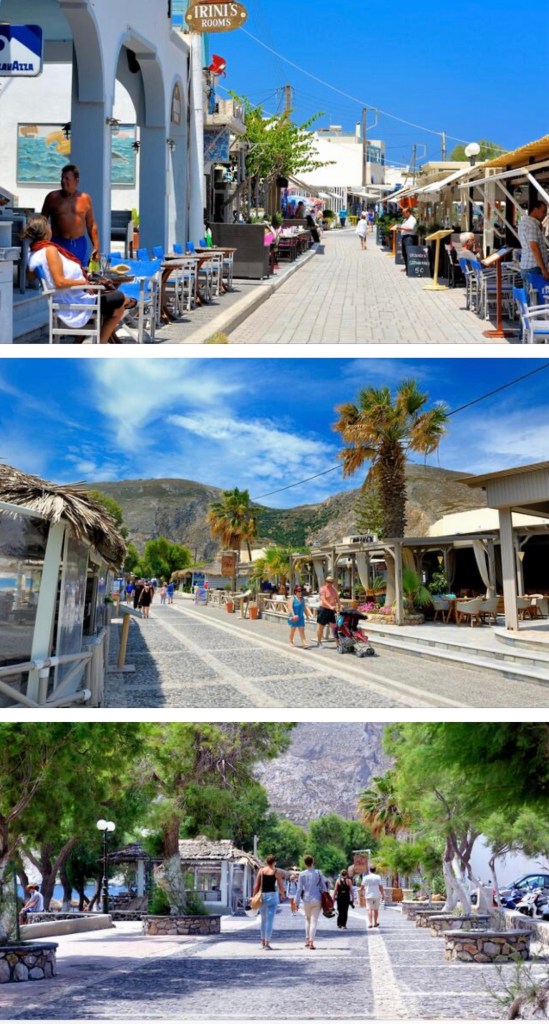

A Postcard from Kamari

Greece was the last place Jane and I met. The hotel we stayed in was vintage in style, located in the heart of historic Athens. From the window, you could see the Parthenon.

A few days later, we departed from the port of Piraeus, taking a ferry to Santorini. Philosophy students might be familiar with Piraeus—Plato’s famous Republic mentions Socrates and his students walking to Piraeus to watch a festival procession. Afterward, they walked back to Athens, where they were invited to a student’s house. That’s how the long dialogue came about—the one that discusses how all children should, from birth, be yanked off their mothers’ breasts and placed in public nurseries alongside other babies, also yanked from their mothers. These kids would then be bottle-fed by women who didn’t have children of their own. Later, when they got older, they’d either be told “You’re going in the dark room!” or thrown in the woods, to be retrieved only if wolves didn’t eat them.

As for books about love? Forget it. Every book had to pass the censors first. Anything deemed immoral or corrupting was censored before it could be read. For example, a text like the one you’re reading right now? Absolutely not allowed!

Santorini attracts visitors year-round. And it’s no wonder—there are very few places like it in the world.

Athinios Port, Santorini

This is how you know love is fading, or has already died: you continue to do the things people in love normally do, but the passion is gone. You still engage in intimacy, but you’re no longer making love. You still hold hands, but it’s out of habit, not affection. You go through the motions because it’s what you’ve always done.

We strolled in Fira, we walked in Oia. We went boating, and we watched the sunset—doing all the things tourists do.

At night, we visited nearby bars. After a few shots of smooth Metaxa, we’d relax, and sometimes it felt like we were rekindling something. Even if the warmth was faint and fleeting, there was a tenderness in those moments—a sense of loss, even forgiveness. The night sky over Santorini was so beautiful, so ethereal.

One morning, after a breakfast of Greek coffee, scrambled eggs, tomatoes, and feta cheese, we rented a motorbike. Helmet secured, we rode to the archaeological site of Akrotiri and then to Kamari Beach.

That day, the beach was packed. Every lounge chair was occupied. Nearby, German tourists, mostly in their sixties and seventies, lounged in the sun. You could tell their age from their unconcerned faces and their wrinkled bodies.

A few young Chinese women roamed between the chairs, offering massages. There were plenty of takers. Jane waved one of them over and chatted with her during the massage, asking where she was from, how business was going, and how often she returned to China.

Meanwhile, I wandered off to find a postcard.

Kamari Beach had a short strip of shops and restaurants with the mountain of Mesa Vouno rising in the background. After some searching, I found a postcard I liked in a small shop.

It was a perfect postcard. Borrowing a pen from the shop, I stepped outside and rested the card on a yellow Hellenic Post mailbox, ready to write. But what should I write, and to whom should I send it?

These questions hadn’t occurred to me earlier when I decided to buy the postcard. I just knew I wanted one to send. But sending a postcard requires a recipient. Who was it for?

Was I thinking of her brother from years ago in Lijiang? Was I unconsciously revisiting that time in my mind? If so, what blessings could I wish him now? Would I repeat what I wrote on the Lijiang postcard years ago? That wasn’t possible.

Would I tell him that Jane and I had reached the end of our road? That our passion was gone? That this was my final letter to him? Certainly not. I had no intention of sharing any of these thoughts.

The mailboxes of Hellenic Post are strikingly bright yellow. I loved them back then and still think they look fantastic even now.

No doubt about it—this is the exact mailbox I leaned my arm on one early summer afternoon many years ago. At the time, I was contemplating the fate of the postcard in my hand. From where I stood, I could see the wide-open beach, rows of lounge chairs, and vacationers in beachwear basking in the sun. The same brilliant sky, the same Aegean Sea, and the same blue waves.

Without a second thought, I pressed the lever on the mailbox slot, released my grip, and let the postcard slide inside. A blank card. No message, no recipient, no return address.

That postcard was meant to remain in Kamari Beach, just as my love for Jane was meant to stay on Santorini. I had loved her for many years. During that time, she had been the solace of my soul.

People go to Santorini for many reasons. Some go for honeymoons, others for clandestine affairs, or to fall in love.

I went to Santorini to bury my love in that beautiful place.