Prologue

The story you are about to read is entirely fictional—except for the last part, which is true. Did you hear me? Reality, you see, is often monotonous, but a good story can entertain. So, I suggest you be patient, read it from the beginning, and don’t rush. It’s just a few minutes of your time, a short piece—not a long-winded essay. If you don’t read it, what else will you do? Scroll through your phone? That’s no better. And if you skim through it lazily, the tribunal’s constables might come after you, or the ox-headed and horse-faced spirits from the City God Temple might drag you away. Not only will you get a beating, but you’ll also be roasted like a Xinjiang-style lamb, and your phone will be confiscated. Wouldn’t you be inviting trouble then? Alright, let’s get to the story.

1

This little restaurant in Puyang Town—I’ve never been here before. I stopped in today after noticing its menu advertised braised crucian carp. I couldn’t resist. It’s just a small family-run restaurant, as ordinary as they come, but that dish was too tempting to pass up.

Sitting next to me was a young girl from Guangdong. She had just arrived in Kunming last night on a train from Shaoguan, speaking Shaoguan Hakka dialect. It sounded neither like Meizhou dialect nor Xingning dialect, and certainly not Cantonese. It always had an odd, peculiar ring to it. Still, I found her endearing.

While we waited for the braised crucian carp, I opened my phone and pulled up a map to discuss with her which places to visit today.

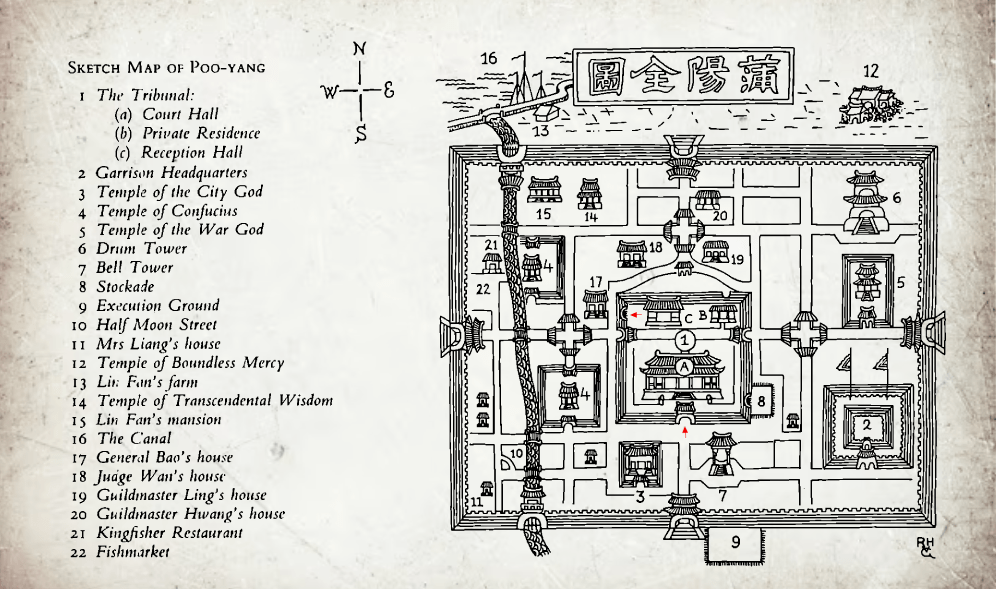

On the map, location 21 was marked as “Kingfisher Restaurant,” the very place where we were now seated near the old West Gate. To the right of the restaurant was a fish market, and to the left, the Li family estate. We chose a table by the window.

It was March, and the willow trees along the Clear Water River were already swaying gently.

If you don’t know foreign languages, have never read the books of the Dutch author Robert van Gulik, or are young like this girl beside me—or if you’ve always lived in a big city and have no concept of small towns, or if you’ve slept through your Chinese history classes—this map might leave you puzzled. Let me explain.

The map is titled “The Complete Map of Puyang.” It depicts Puyang, but it’s also a typical example of maps from small-to-medium-sized towns in historical China. The town was once surrounded by walls. Though only a few sections of earth wall remain on a small hill behind the town, people here still refer to the East, South, West, and North Gates as they used to. The waiter who took our order at Kingfisher Restaurant called the nearby area the “West Gate.”

Location 2 on the map is a training ground (historically pronounced as “jiaochang”), which became the public security bureau after Liberation.

“No wonder there’s a Guandi Temple (5) behind the public security bureau,” my companion remarked. “We have Guandi temples in my hometown too.”

“You’re clever,” I praised her. “Hearing about weapons and soldiers, you immediately connected it to the War God. After lunch, let’s head to Half-Moon Street. The City God Temple is there, and someone was once hanged inside.”

Her face flushed, and I noticed a nervous energy about her. I pretended not to see it.

“There’s also a chastity arch in Sanpu. Would you like to see that too? Are you scared?”

“I’m not scared!” she said, trying to appear calm. She couldn’t hide her curiosity, though, as she asked, “You mean an arch built to honor widows who remained chaste? Like Indian widows who burned themselves on their husbands’ funeral pyres?”

“It’s not that extreme,” I said. “These arches were erected for women who upheld chastity, like those who hanged themselves rather than remarry under pressure from their in-laws.”

She opened her mouth as if to say something but stopped. At that moment, our dish arrived. The crucian carp, each about the size of a hand, were stewed in local fermented sauce with garlic and chives, served in a large earthenware bowl. It looked delightful. But the girl who had just been complaining of hunger now seemed to have lost her appetite. She stirred her rice with her chopsticks, deep in thought.

2

Between studying the map and eating, I forgot to explain how we ended up in Puyang.

In early March, my mother passed away. I rushed back to Kunming from the U.S. to handle her funeral. Funerals are never pleasant—so noisy and crowded. The day we carried her ashes for burial, I could feel her skull shifting inside the urn with every step I took.

In short, it was a grueling process: burning incense, bowing, hosting guests, and dealing with endless formalities. My mood was terrible.

When it was all over, I had a few days left before returning to the U.S. I didn’t want to see anyone or go sightseeing. I had a bottle of whiskey by my side, but it wasn’t something to drink first thing in the morning. Sitting alone, staring at my mother’s empty room, felt unbearable. The house was so empty—how was I supposed to spend my days there?

Five years ago, before I left China, I had met this girl while skateboarding. She was from Shaoguan, spoke Hakka, and also knew Mandarin. We skated together, rode BMX bikes, and volunteered at competitions. Afterward, we’d grab meals.

The more time we spent together, the more curious she became about my life. She’d ask endless questions: Where did you grow up? What was your childhood like? What were your kindergarten and elementary school like?

Her biggest wish, she said, was for me to take her to my childhood hometown and retrace the paths I walked as a boy. After COVID came, five years passed without me being able to return, and many promises went unfulfilled.

Sitting on that cold sofa one night, holding a $1,000 bottle of whiskey a wealthy friend of mine had gifted me, I picked up my phone and called her on WeChat. As the ringtone played, I stared at the empty room around me.

When she answered, her voice was full of surprise. I said, “Yeah, yeah, Xióng’áo, it’s me. Bet you didn’t expect this, huh? I’m in Kunming now. I didn’t tell you beforehand. I’ve got a few days here. Come over. I’ll take you around.”

It’s only a seven-hour train ride from Shaoguan to Kunming. The next evening, I met her at the metro station. She had long hair, a slender frame, and was dragging a large suitcase through the ticket gate. And that’s how it began.

3

After lunch, we strolled south along the river toward the South Gate. Crossing Clear Water Bridge, we soon reached Half-Moon Street—location 10 on van Gulik’s map.

There was a house we always passed along this street, with an old wall plaque bearing the slogan: “Chairman Mao is the red sun in our hearts.” Another wall nearby read: “Peas. Corn.” I never knew what it meant.

As a child, I’d peer through the narrow cracks in their windows, always wondering what was hidden behind the shutters. Patients? Mute prisoners? Kids locked in a dark room?

We continued east and arrived at the old City God Temple, marked 3 on van Gulik’s map. From the outside, it looked grand and well-maintained, with some sections clearly renovated. My companion wanted to go in, but I warned her, “I told you, someone died here before.”

“I’m not afraid!” she said.

Inside, there were no Buddha statues, Bodhisattvas, or deities—just a magistrate-like figure called the Judge, flanked by ox-headed and horse-faced statues.

“There’s a Chinese proverb,” I told her. “‘The Judge’s face—a grimace of bared teeth.’ It’s true.”

But many items in the hall seemed shoddy, likely the result of budget renovations. The atmosphere was unwelcoming.

“You said someone died here before?” she asked.

“Yes,” I replied. “A low-ranking official during the Cultural Revolution. He was publicly criticized, and his wife disowned him to save herself. One night, unable to bear it, he hanged himself from a beam in this very hall.”

She didn’t respond, but I could see her glancing around, craning her neck to examine the beams.

“You’re wondering which beam he used, aren’t you?” I asked casually.

Startled, she stammered, “No, no! What are you even talking about?”

Instinctively, she touched her neck, pulling her collar higher as if shielding herself. Though it was a sunny March day, the temple felt chilly.

As we left, she asked, “You were so young back then—how do you remember all this?”

“I remember plenty!” I said. “By that bridge over Clear Water River, I once saw a newborn baby floating, its umbilical cord still attached…”

Before I could finish, she grabbed my arm, shaking it as if to stop me.

We stepped out of the temple into the street, which was quiet and bathed in warm sunlight. The chill of the temple was gone, and we both felt much better.

She wanted to look at the map again. I took out my phone.

“Are we here?” she asked, pointing to the map.

“Yes,” I replied.

“What’s marked with 9 on the map?” she asked.

“That’s the execution ground, outside the old South Gate. It used to be where criminals were beheaded.”

“And what about 12?” she asked.

“Oh, that’s the Dabeiyuan (Temple of Great Compassion),” I said.

“Why are the execution ground and Dabeiyuan both outside the city walls?”

“Because the city represents the realm of the living, and outside the walls is the realm of the dead,” I explained. “The living dwell in the city, while the dead remain outside. It’s the idea of keeping the worlds of the living and the dead separate.”

“I want to go and see it,” she said, biting her lip.

“The execution ground? There’s no need to visit. It’s just like the old Caishikou in Beijing, where they used to execute people—nothing to see. If you do, ghosts might cling to you, and you won’t be able to sleep at night. But the Dabeiyuan is worth visiting. Do you want to go there?”

“Yes!” she said.

“Alright, we’ll go to the Dabeiyuan today,” I said. “Tomorrow, we’ll visit the Confucian Temple and the Tribunal. But we’ll need to rent an electric scooter. It’s not close!”

We found a row of yellow electric scooters for rent by scanning a QR code. I unlocked one, got on, and gestured for her to sit in front of me. She refused, saying that only married couples sat like that. Instead, she insisted on crouching awkwardly in the footwell. There was nothing I could do, so I let her be. She stayed curled up like a vegetable basket the entire way. What could I do? She refused to sit properly!

4

I had been to the Dabeiyuan as a child and still had some memories of it. I knew it was famous for its Guanyin Hall, which was always bustling with incense and prayers. However, I was never particularly drawn to Guanyin. Instead, I always felt a special connection to the Ksitigarbha Hall.

Whenever I visited a temple, I would make a point to see Ksitigarbha and sit in the hall for a while. I couldn’t explain why. Maybe it was because Ksitigarbha is associated with guiding the dead to the afterlife, and I’ve always found the dead both terrifying and strangely fascinating. According to Buddhist scriptures, Ksitigarbha vowed not to attain enlightenment until “all beings are saved, and hell is empty.” Perhaps it wasn’t a coincidence that I felt a bond with him.

By the time we arrived, it was already late. There weren’t many people in the temple. The Guanyin Hall was still open, but the main hall had closed. We spent some time sitting in the Ksitigarbha Hall, where a sleepy nun selling incense dozed nearby.

After leaving the temple, we still had some time, so we decided to take a walk up the mountain. However, since it was the spring fire prevention season, guards stopped us from going further into the forest. Feeling a bit disappointed, we followed the firebreak trail for a while. Soon, we came across a newly constructed park. The stone steps were pristine, and the trees and shrubs had clearly been freshly planted, as evidenced by the red soil around their roots.

Beyond the park, a dark mountain peak loomed ominously against the bright sky, its blackness incongruous with the sunny day. We climbed the stone steps to the top, reaching a circular platform about 100 meters in diameter. The ground was paved with stone, surrounded by towering pines.

I was about to approach the edge when I caught a faint, metallic scent—blood. The wind on the platform swirled chaotically, without direction. Though it was a clear day, I felt as though dark clouds were gathering overhead. A sense of dread washed over me, as if I could feel the presence of someone who had met a violent end here.

Uneasy, I turned to call my girlfriend. She was on the other side of the platform, taking photos. My mouth opened, but no sound came out. My feet felt rooted to the ground, unable to move.

“What’s wrong?” she asked, walking over and shaking my arm vigorously. “What’s wrong with you?”

“I… I don’t know,” I stammered, snapping out of my trance. “What happened?”

“I was taking pictures and saw you just standing there, not moving. I thought something had happened to you.”

“That’s so strange… really strange,” I mumbled, my words slurring. “Didn’t you feel it?”

“Feel what?” she asked, confused.

“Never mind. Let’s go. We shouldn’t stay here,” I said, still shaken.

That evening, we returned to town and had dinner at a Halal restaurant near the North Gate. Cold beef slices, flatbread, and lamb soup with mint—it was delicious, but no amount of hot soup could warm the chill I felt inside.

5

That night, I couldn’t sleep well. I kept waking up. When I finally managed to drift off, I had strange dreams.

In one, I fell into the water and kept sinking, unable to reach the bottom. Bubbles rose endlessly around me.

In another, I was on the mountain in the rain, searching for shelter, but fog surrounded me on all sides, and no matter how far I walked, I remained in the same spot.

In yet another dream, my girlfriend and I were riding a yellow electric scooter to an unknown destination. The scooter made no sound as it moved, and instead of riding on the ground, we seemed to be floating in the sky. My feet couldn’t find solid ground—it felt like every step would plunge me into an endless abyss.

The next morning, I woke up with a splitting headache. Desperate for relief, we went in search of coffee. That’s when I realized how amazing the espresso in my hometown could be—far better than anything I’d had in Paris, Rome, or the U.S., and available everywhere!

We sat by a window, enjoying our coffee and pastries. Outside, palm trees swayed gently in the faint morning mist. The soil here seemed to grow anything—from southern gingko, wintersweet, and camphor trees to tropical palms. Everything thrived with exuberance.

As we sipped our coffee, I took out the map again. Today’s plan was to visit the Confucian Temple, followed by the Tribunal, and then say goodbye to the town.

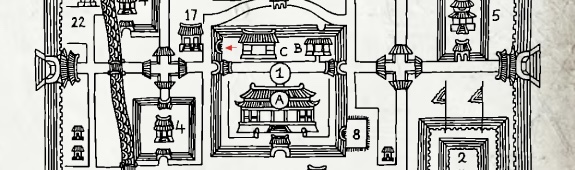

“Look,” I said, pointing to the center of the map, “this spot marked 1 is the Tribunal.”

“What is a tribunal for?” she asked.

“Back then, the Tribunal was essentially the county government,” I explained. “If you combined today’s county office, tax bureau, court, and police station, that’s what the Tribunal used to be.”

“But I also want to see the Confucian Temple,” she said.

“Sure,” I said. “We’ll go there first…”

Before I could finish, we saw a scooter on the road outside crash into the back of a small truck that had stopped suddenly. The scooter toppled over, and the rider and their bag were thrown far away. After a while, the rider slowly got up.

Having witnessed the accident, we were both stunned and struggled to catch our breath.

“She seems fine, doesn’t she?” my girlfriend asked, visibly uneasy. “I hope she’s okay.”

A few passersby stopped to look but soon moved on.

6

The entrance to the Confucian Temple isn’t directly on the street, but its archway is, and you can see it from far away. The archway, called the Arch of Civilization, was built in 1744. It’s entirely wooden, without a single nail.

I remembered that there used to be a well near the temple, and I was curious to see if it was still there. I asked her to come with me to look for it. Before I could finish, she interrupted me quickly, “Don’t tell me someone drowned in that well—I don’t want to hear it!”

“I didn’t say anything about someone drowning!” I said. I couldn’t help but find it odd—how did her thoughts align so closely with mine? Because I had been wondering, Could something like that have happened in the past?

The well was still there, just as I remembered. A man was squatting by it, washing clothes. He told us that although the well was still intact, the water had become polluted and was no longer drinkable.

How could this be explained? There were no factories nearby, so where could the pollution have come from? I couldn’t figure it out. When I asked the man washing clothes, he said he didn’t know either.

On the other side of the Confucian Temple, there used to be a kindergarten. We decided to check if it was still there. Sure enough, it was, though it was no longer a daycare. I pushed the vermilion door gently, and it creaked open. I didn’t step inside, just poked my head in for a look. She was right behind me, clutching the corner of my shirt.

“What do you see?” she asked.

“Don’t be nervous,” I reassured her. “It’s just an empty courtyard, nothing special.”

Back when I was in school, the Confucian Temple had two main clusters of buildings. One was called Hongxue (宏学), marked as (lower) 4 on van Gulik’s map, which served as classrooms for grades one to three. The other was called Dadian (大殿), marked as (upper) 4, where grades four and five had their classes.

I didn’t understand why it was called Hongxue until I went to college and studied The Rites of Zhou in The Thirteen Classics. As a child, I thought Hongxue simply meant “Red School.”

Thinking about The Rites of Zhou reminded me of the archaeological materials I read in college. There was always news of tomb excavations—today in Hubei, they’d unearthed nine great ding (ritual cauldrons), nine gui (grain vessels), nine zun (wine vessels), nine jue (wine goblets), nine jia (tripod cups), and a pile of human bones from sacrifices. Tomorrow in Henan, they’d find seven of each. I always felt a sense of decay and rot when reading those books and didn’t particularly enjoy them.

The Hongxue buildings have largely lost their original appearance. The Dadian and the side rooms are completely gone, leaving only two sections of stone steps that can still faintly be made out.

“Imagine this,” I said to her. “During recess, a hundred or so children ran up and down these steps. There were no safety railings on either side. Every day, kids would rub crayons on the stone slabs to make them smooth. Over time, the steps became as slippery as if they’d been oiled. You’d barely sit down before sliding off. And yet, everyone fought to sit there. Back then, it seemed like people’s lives weren’t worth much.”

“I remember hiding a spent rifle shell in one of these cracks in the steps,” I added, “a souvenir from the armed clashes during the Cultural Revolution. It might still be here. Let’s look for it!”

“Why did you hide it here?” she asked.

“I brought it to show off to my classmates, but there were always bullies who would steal your stuff. So, I hid it here when no one was looking. Then I forgot to take it back.”

She and I each took a section of the steps, carefully inspecting every crack from bottom to top, but we found nothing. The rifle shell was gone.

On the hillside next to Hongxue, there’s a Hélílè tree that’s been there since I was in elementary school. It’s still there today, tall and sturdy, just as I remembered it. As children, we used to call it the “betel nut tree,” though that wasn’t its real name.

In ancient texts, the Hélílè tree is often mentioned. In the book Jingui Yaolue by the medicine man Zhang Zhongjing (~150 CE – ~ 219 CE) for example, it says this: “For diarrhea caused by Qi, promote urination. Hélílè powder is the remedy.” In the Buddhist book Kun Nai Ye Miscellanies one finds the following: “Hélílè, Amalaki, Bibhitaki, Piper nigrum—these five herbs can be eaten anytime, regardless of illness.”

7

After lunch, we went to visit the Tribunal. It was on Shangyi Street, a narrow street between the City God Temple and the Confucian Temple. Standing in the street, we took a moment to observe the entrance.

“This is it?” she asked.

“Yes, it might not look like much now,” I said, “but back then, this was a real tribunal—a place everyone feared. There’s an old Chinese saying: ‘The Tribunal faces south; if you have reason but no money, don’t come in.’ That’s what this place was about. Another saying goes: ‘Officials don’t renovate their tribunals.’ It means that officials didn’t dare rebuild the tribunal. That’s why it looks so shabby now.”

“Why didn’t they renovate it?” she asked.

“Because if the emperor explicitly ordered them to, they’d take advantage of it to exploit the people and build grand government buildings. But if there wasn’t such an order, they’d avoid renovations out of fear of being impeached for overspending. So, over time, tribunals fell into disrepair.”

Looking at van Gulik’s map, I pointed out how accurately the tribunal was depicted. The main gate indeed faced south, just like the one we were now seeing in Puyang. However, back in the day, there would have been stone lions on either side of the entrance and guards with spears standing watch.

Before we entered, I showed her the map again to give her a clearer idea.

The tribunal in Puyang had three halls:

1. The Main Hall (Dàtáng, 1A): This was where cases were heard, sentences were pronounced, and punishments carried out.

2. The Inner Hall (Nèitáng, 1B): The office space for the county officials.

3. The Rear Hall (Hòutáng, 1C): The private living quarters of the magistrate and his family.

“And here, at 17 on the map, is the residence of the Public Security Bureau chief,” I explained. “When you’re recording later, make sure to get all three halls on video.”

As I finished explaining, an unexpected sense of melancholy washed over me. She noticed immediately—she was good at sensing my mood.

“What’s wrong? You don’t seem happy,” she asked.

“Nothing,” I lied, trying awkwardly to cover my emotions. “I was just reminded of my school days. Behind the tribunal, there was a small side gate. It led directly to the street in front of my school. I often took that shortcut—through the tribunal, up to the side gate—because otherwise, I’d have to walk to the end of the street, turn a corner, and go uphill. It was much farther.”

I took out the map and pointed to a red arrow.

“See that red arrow on van Gulik’s map? That’s it! The secret passage. Hardly anyone knew about it. It didn’t save that much time, but using it felt like having a little secret. Later, I’ll show you that back gate, if it’s still there after all these years.”

The path from the tribunal entrance to the Main Hall was paved with blue slate. As a child, it had seemed endlessly long, but now it felt like only a few steps. Unfortunately, the path was now lined with illegal buildings, making it hard to imagine the grandeur it once held.

She began recording and walked ahead while filming.

In the days of old, as you entered the Great Hall you’d see the magistrate’s desk with a plaque on the wall behind it reading “A Mirror of Justice Hangs High.” You’d also see on the sides weapons rack and rods used for punishing criminals.

After passing through the Inner Hall, we stopped to rest briefly.

“If I remember correctly,” I said, gesturing in a certain direction, “the small back gate of the Rear Hall should be over there.”

The steps leading to the Rear Hall were still intact, but illegal buildings crowded both sides, leaving only a narrow pathway. It took some effort to reach the top, only to find that the courtyard of the Rear Hall was nothing like before.

The courtyard, once home to families and trellises of gourd vines, was now filled with abandoned makeshift structures and piles of construction debris.

“The gate should be here,” I said, walking toward the northwest corner of the Rear Hall. I pushed aside some rubble as I went.

“Let’s not go any further,” she said, visibly uneasy. “It’s dirty and deserted here.”

But I wasn’t paying attention. Something ahead looked familiar, and I became excited.

“This is it! This is it!” I exclaimed, my heart pounding. I stumbled forward, kicking up loose bricks and rubble, my eyes fixed on the corner.

To my amazement, the small iron door was still there after all these years! The sense of secrecy and childhood wonder came rushing back.

The door was a rusty sheet of metal embedded in a crumbling wall. No plants grew on the wall now, though there used to be some on top of it, usually dry by spring.

By this time, she had caught up to me, standing close enough for me to hear her breathing.

“Is this the door you were talking about?” she asked, pointing to the wall.

Overwhelmed with nostalgia, I didn’t respond. Without thinking, I grabbed the handle and tugged. The door didn’t budge. I pulled harder a few times.

“Maybe it’s stuck. Let’s just go,” she urged. “It’s getting late.”

“Strange,” I muttered, brushing rust off my hands. “Maybe I’m mistaken. Could it open inward instead of outward?”

The idea struck me, and I pushed the door instead. It gave slightly. Excited, I pushed harder.

“It opens inward! I can’t believe I forgot that after all these years,” I said.

She seemed both intrigued and anxious, her eyes darting around as if expecting something.

After a few more pushes, the door creaked open with a loud crash, causing part of the wall to collapse. I nearly lost my balance. As I steadied myself, I looked up and gasped, “What the hell?”

Behind the door wasn’t the street I remembered but a small, crude shed—a makeshift storage space. The air reeked of burnt materials, concrete dust, and charcoal.

Inside the shed, in one corner, lay a tightly bound bundle resembling bedding. It was greasy and blackened, with what looked like long-dried stains. Nearby, charred earth bore marks of fire.

She gasped, covering her mouth with her hand. “What… what is that?”

I realized instantly: this wasn’t just a shed; it was a crime scene.

We bolted out of there, running until we could catch our breath. After calming down a bit, I said, “What now?” It was unclear whether I was asking her or myself.

“We need to leave!” she insisted.

“No,” I said firmly. “We have to report this. If we don’t, and they investigate, we could be in trouble.”

We walked back to Shangyi Street, where we saw a police motorcycle parked on the side. We approached the officer and explained what we had found.

“Wait here. Don’t leave,” the officer instructed, picking up his radio to make a call.

8

The police station was located in what used to be the training grounds near the old East Gate, marked 2 on van Gulik’s map.

Because I was a foreigner and she was from another province, the process was more complicated. First, we were taken upstairs to register, fill out forms, and provide fingerprints. An officer photocopied our IDs. While copying my passport, I noticed a few officers passing it around, curious—it was probably their first time seeing an American passport.

Afterward, I was taken to the interrogation office to give a statement.

“What about her?” I asked, pointing to my girlfriend.

“She’s fine. Don’t worry about her,” the officer replied.

The interrogation room had recording equipment for audio and video. I recounted everything we discovered at the tribunal that afternoon. The officer questioning me, a man in his thirties, remained expressionless throughout. Once the statement was recorded, I read it over, confirmed its accuracy, and signed it, leaving a fingerprint as confirmation.

9

Kunming South Railway Station, early morning.

The taxi dropped us off at the departure area. I helped her drag her suitcase to the station’s glass wall. Commuters bustled around us, boarding early high-speed trains. The sun hadn’t risen yet, but the horizon was beginning to brighten.

“You’re going back to America tomorrow,” she said.

“Yes,” I replied. “Who knows when I’ll be back.”

She was quiet for a moment. Then she asked, “Will you come into the station with me?”

“No,” I said. “I’ll say goodbye here.”

She didn’t reply, but her eyes turned red. I gave her a hug.

“That poor woman,” she murmured.

The Puyang police had worked quickly. Though they hadn’t found the killer, they had identified the victim. She was a Sichuanese woman who had disappeared from town ten years ago. She had worked as a singer at a local karaoke before vanishing.

I checked the time. Her train was about to board.

“You should go, Nanke,” I said.

It was the first time I called her by her real name—not the Hakka “Slim Sister,” not “Hey,” not “You,” but Nanke.

As I watched her walk toward the station entrance and disappear into the crowd, I felt as though a part of me had left with her. At the same time, I felt I had gained something from her—a part of me I hadn’t known existed. My throat tightened.

On the subway ride back to town, I stared out the window at the fleeting spring landscape, thinking, To lose something is to gain something else. Perhaps that’s life.