1

Every day, I drive to work. First onto Genesis Road, then onto 540, followed by Mill Road, and finally a turn onto Seagull Road. There is no mill on Mill Road, no sea on Seagull Road, and certainly no seagulls. Just endless roads, wild grass, green fields, and clouds on the horizon.

Life has taken me to foreign lands, and many years have passed. Every day, I work from 9:00 to 5:00. On my desk, two large monitors display software, data, reports—curves, QC’s. Coffee, and more coffee. Standing in front of the Bunn automatic coffee machine, waiting for my coffee, I hear the ad on the machine’s screen playing over and over: “une tasse à la fois.” If you’re getting older, that should be your approach to life—one cup at a time, one day at a time.

Back when I taught in Michigan, every time I went to get a haircut, the old white barber would always say to his customers: “Just take it one day at a time.” Once you reach a certain age, some truths cease to be true. Chairman Mao once said, “Do not eat into past achievements; strive to make new contributions.” But if you ask me now about making new contributions, I’d just tell you, “Forget it!” Of course, I never say that out loud while standing in front of the coffee machine. Even if I did, no one would understand. Even in China today, no one would understand.

As a child in China, I didn’t understand it either. What I did remember was always being hungry. Seeing the slogan on the wall—“Do not eat into past achievements; strive to make new contributions”—I thought: I don’t know what past achievements are, but if they’re something edible, wouldn’t that be great? Maybe past achievements are like roasted yams or baked sweet potatoes. Then why not eat them? I don’t want to listen to Chairman Mao anymore—I want to eat past achievements!

On my way to work, I always pass by a curling rink. It’s usually closed, only opening in winter. During the season, even people from Canada drive here to compete. A sign says the club has been around for over a hundred years. County police often park in the empty lot of the curling club—probably eating lunch, or maybe doing something else.

I once had a student who served at a military base in Iraq. After graduating from college, he became a state trooper. Not long after, he was fired for stopping women drivers without cause and making inappropriate requests.

Where did his coffee and donuts go? Probably long gone by now.

The seasons pass. At night, I return home, watching the clouds rise, the sun set, and sometimes, a half-formed new moon. Before I realize it, old age is creeping in.

2

I often think of the past. I remember graduating from university and going to teach at a geology team. The team was deep in the mountains. From the provincial capital, the long-distance bus took a full day. That was many years ago.

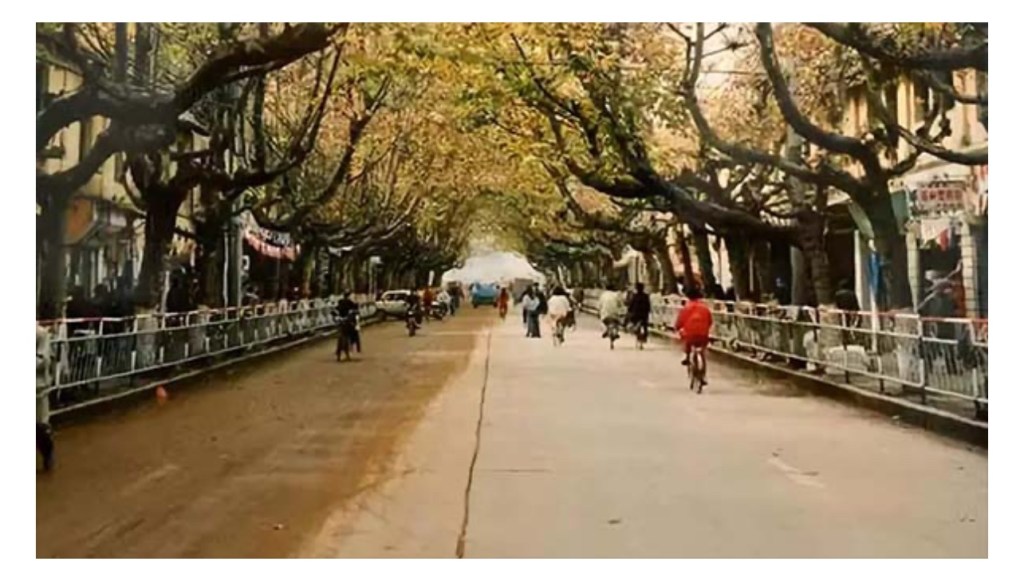

The bus looked like this:

That year, I was 21. What did I look like? Did I look like this?

No.

Like this?

No. Maybe like this?

Too Republican-era—definitely not! This one?

Still not quite right.

I had an army-green canvas suitcase and a duffel bag. Both were thrown onto the roof rack and strapped down, just like people do today in India or Bangladesh on long-distance buses. So this picture is closer to reality. If you add a bit of leftover snow on the roof and some heavy clouds instead of sunlight, then it would be exactly how it was back then.

Wow—I was about to embark on my journey to the geology team! I was so excited!

3

The geology team was in the northeastern part of the province, a region home to the Hani, Yi, and Hui ethnic groups. The town had a market every five days. On market days, caravans from the mountains would pass by the school. You could hear the jingling bells of the mule trains from the office.

The Hani and Yi girls were beautiful—what China’s internet people today call “颜值” (“face value”), no doubt a term coined by some half-bottle-full dropouts who had just returned to China from the U.S. and later caught on with the rest of the population: the half-bottle-empty Chinese who had never studied overseas.

Here’s a Hani girl:

Thinking back, it wasn’t just Hani girls—everyone on the plateau had those sunburned red patches on their faces. The only ones without them were pugs, potatoes, cucumbers, green onions, and earthen pots.

Yi girls were different—fair-skinned:

The Stone Forest and Lugu Lake are stunning places, both in Yi territory. If you haven’t been to Lugu Lake yet, you must go.

4

I had a girlfriend when I graduated—my dear Alili. We were a perfect match, destined to marry. Our families had already met, and everything was proper and legitimate.

Alili’s mother worked at a bank in the provincial capital, and so did Alili. Her father was a forensic pathologist at the provincial public security department—famous throughout the province. His bookshelf was filled with forensic science books. An avid reader as I am, I never touched them, fearing I might see things I couldn’t unsee.

This is my Alili. (Hello, Alili, I love you!)

After I left for the geology team, I saw Alili less often. When I had the chance to return to the capital, I stayed at her house. One night, while reading, I accidentally knocked over the sofa backrest, making a loud noise. I probably woke her entire family.

Our base camp was on a mountain slope, with a ravine separating the geology team and the school. A bridge connected the two.

I shared a dorm with a graduate from Sichuan Geological College. He loved working on semiconductors—our desk was covered in dismantled radios, soldering tools, and electronic components. A typical engineering student.

One day, I found a Swan Lake record in the school’s broadcasting room—performed by the China National Symphony Orchestra. I urged my roommate to fix the old phonograph so we could play it. Once he did, we played it every night for weeks on end, under the moonlit sky after the students had left. For years afterward, every time I heard Swan Lake, I’d get a headache. We played it so much.

Next door lived a young female teacher—Ms. Kou. Before I arrived, my roommate had never interacted with her. He was shy. But with two people, there was no longer any awkwardness. We often visited her dorm to chat.

She was from Henan and once taught me how to say flourishing in the Henan dialect. If you’re from Henan, you’ll know what I mean. If not, find someone from Henan and ask them to say “flourishing”—you’ll understand.

Ms. Kou later took an English course at the provincial foreign language institute. There, she met a classmate—a relative of Nie Er, the composer of China’s national anthem. He was from a well-established family, with a house on Jinbi Road in Kunming.

One day, she took me to his home while he was away. Through the window, I saw the bustling traffic (or lack thereof) and sycamore-lined streets of Jinbi Road. The house had many rare books, including an English Bible. I borrowed it and kept it for a long time—until they broke up.

Old family legacies are hard to understand unless you’ve seen them firsthand. I saw similar ones in Tianjin—nothing like the overnight riches of the nouveau riche.

Ms. Kou was two years older than me. She liked me—I knew that. But she also knew I had a girlfriend, knew my girlfriend’s name was Alili. She often teased me about her, frequently asking, “Has your Alili written to you again?” or saying, “It’s been so long since you’ve seen Alili—you must miss her, don’t you?” And when a holiday was approaching, she would grin and say, “You’ll be seeing your Alili soon. You must be excited!”

My relationship with Ms. Kou was special—almost as if we had been together in a past life, as if we had lived side by side for centuries. There was no barrier between us.

Her family lived in the provincial capital. When we traveled back on break, I would rest my head on her arm and fall asleep on the bus. When I was in the city, I would visit her at home, sometimes taking a shower there. At the geology team, when market day came and I bought new clothes, I would go to her dorm, take off my old clothes in front of her, and try on the new ones—without feeling the slightest awkwardness or self-consciousness. It was an unusual kind of closeness.

Even when we were alone, if I placed my hand on her waist, my blood pressure didn’t rise, my heart didn’t race, and no surge of passion took hold of me.

I knew she liked me. I liked her too. But it was a kind of liking that felt eternal—so familiar, so natural, that it settled into the background, as ordinary as a home-cooked meal.

But every day, all I talked about was my Alili. Her father worked as a forensic pathologist at the provincial public security department. He was thin, with a cigarette always trailing a curl of smoke between his fingers. He looked remarkably like the old American movie star Humphrey Bogart.

Alili once made a vow to me—she was determined to write a book titled A Forensic Pathologist’s Daughter.

Her father had worked on a case where a reservoir’s equipment shed was frequently burglarized. The reservoir manager set a chain of explosives as a trap but ended up blowing himself up, losing both his legs in the process. It was a tragic story.

In another case, he investigated the body of a headless pregnant woman pulled from Lake Chengjiang. I can’t recall if Alili’s father solved these cases or not.

During the holidays, I went boating on a lake with Alili’s family. Later, we went swimming. Her parents and two younger sisters stayed on the boat. My swimsuit was a little short, and a lot of body hair was showing. Her father had a Seagull camera and took many photos.

Thinking back on it now, I feel a bit embarrassed. I hope those photos didn’t end up in any criminal records, displayed in courtrooms, or included in textbooks.

But when you’re young, you don’t think much about such things. The water was so clear, the sunlight so brilliant. Being an ordinary future son-in-law—even if awkward—left nothing to regret.

5

I taught both middle and high school students at the geology team. What kind of teacher was I? Let me put it this way: later in life, I met a white woman who once told me bluntly, “You’re a transparent person.” She was probably right, though I couldn’t quite define what that meant. One thing I do know—transparent people don’t make good teachers. Even middle school students could see right through me.

Every time I walked into my ninth-grade classroom, I would find a branch, carefully trimmed into the shape of a switch, placed on my desk—clearly meant for disciplining students. They had put it there on purpose, as if challenging me. I would stand before it, hesitating for a long while. My hesitation delighted the students. The longer I wavered, the more they knew they had won. They understood that no matter how long I hesitated, I would eventually pick up the branch, hold it in my hand, and walk up and down the classroom, with a grave look on my face. Being able to predict their teacher’s thoughts filled them with triumph.

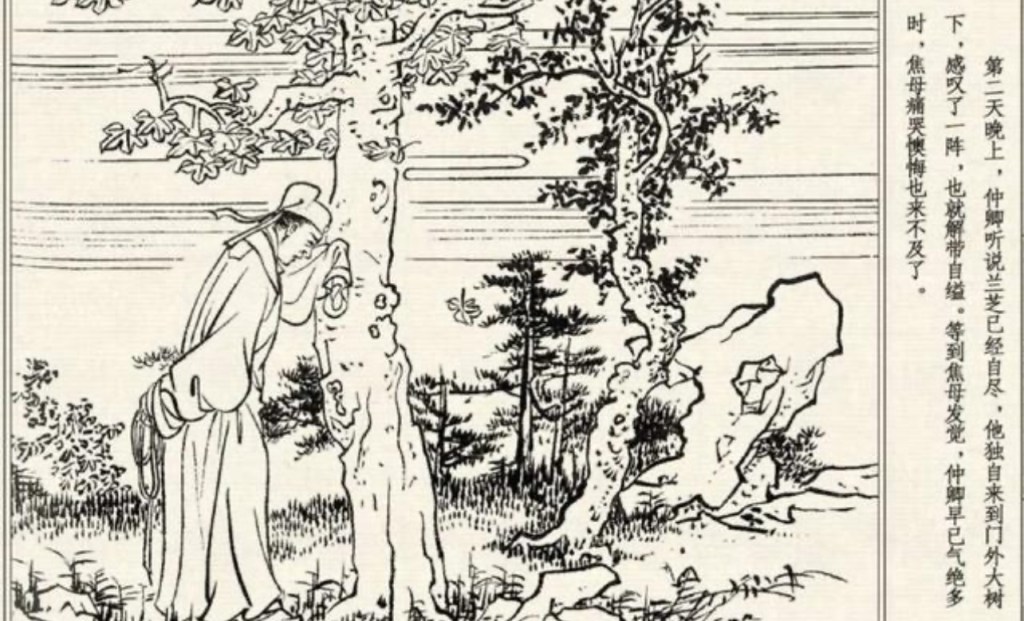

What did I teach in high school? I don’t remember much—except for Peacock Flying Southeast and Lu Xun’s In Memory of Miss Liu Hezhen. Lu Xun’s essay is no longer in today’s high school curriculum, for reasons unknown. Back then, it was included.

Reading In Memory of Miss Liu Hezhen and In Memory for Forgetting, I always felt an inexplicable sorrow when Lu Xun wrote:

“Again and again, grief and rage strike at my heart.”

“The butchers roam free and unfettered.”

Looking back now, I realize these are not easy subjects for high school students. Perhaps they should be taught at the university level.

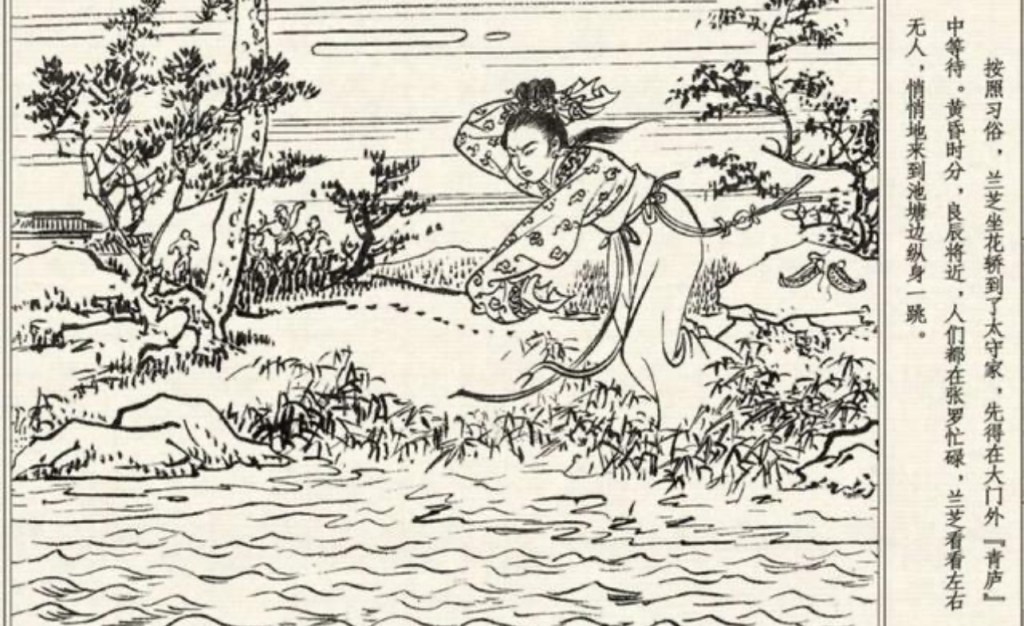

I’m not sure if Peacock Flying Southeast is still in the curriculum. In it, the tragic lines—

“He hanged himself from the southeast branch;

She threw herself into the clear pool.”

—were supposed to be moving. But whenever I reached this part, my clueless students—boys and girls alike—would giggle foolishly. It made me exasperated, but there was nothing I could do.

Among the students in the “He hanged himself from the southeast branch” class was a 16-year-old girl named Li Rui. She had a delicate oval face, a long slender neck, and a short ponytail tied neatly at the back of her head. She was thin, like a matchstick, her limbs as slender as twigs. She was just a young girl, looking something like this:

She was a local, unlike the geology team’s children, who spoke Mandarin at school. With me, she spoke in her native dialect. Thinking back, she would blush every time she saw me.

One afternoon, I was in the office grading papers. It was late—most teachers had gone home. Only one young teacher, a heavily pregnant woman from Sichuan, remained in the corner of the office.

Li Rui peeked in, glanced around, then tiptoed inside. She placed a brand-new thermos on my desk and said, “This is for you.”

Only after speaking did she realize there was someone else in the room. Her face turned red, and she quickly withdrew. That pink, flustered face—I can still remember it vividly.

On Teachers’ Day, students came to clean for the unmarried teachers. The high school girls washed clothes in the courtyard, singing as they scrubbed. The boys swept the floors. The weather was beautiful, the sun shining bright.

Freshly washed sheets and garments hung on lines, fluttering in the breeze like rows of international flags.

I sat on the edge of my bed in my second-floor dormitory, playing the accordion. What song was it? I can’t recall—probably some Russian folk tune.

Mountains flanked the dormitory on both sides. The wind blew in through the wide-open windows and out through the open door. From there, I could see my students—boys and girls, sixteen or seventeen years old—like clouds drifting in the blue sky, like wind sweeping the earth.

That was youth. That was joy. A joy so overwhelming, it had no reason to exist.

At first, Li Rui was with the others washing clothes in the courtyard. Later, she came up to my room and sat beside me. She wore a white short-sleeved shirt that revealed her flat, undeveloped chest without a bra. She spoke without making eye contact, tugging absentmindedly at her collar, as if trying to cover herself.

She asked me many questions. What kind of questions? I don’t remember most of them. Maybe nothing special—just chatting. Half of my bed was piled with books. From Wang Xianjun’s Introduction to Mathematical Logic to Shen Fu’s Six Records of a Floating Life—a complete mix of subjects.

“Are these all the books you read, Teacher? So many books! Do you like it here? Are you used to life here? Is the city nice? Is it cold studying in the North?”

During spring break, the entire class went on a two-day trip to a Hui Muslim village in Baishui Town.

Each boy was responsible for a bicycle and a girl. I didn’t have a bike, so Li Rui brought one from her home. When it came time to pair up, she insisted on being with me. Well, if she wanted to be with me, so be it—I was more than happy to have her by my side.

The road was about ten kilometers, through mountainous dirt paths. When it got too rough to ride, we walked, pushing the bike. Most of the time, Li Rui sat on the back rack, gripping me tightly.

That night, more than ten of us stayed at a villager’s house. We gave them ten yuan for food and lodging—a considerable sum at the time. The elderly lady of the house was deeply grateful.

We spent the night by the fire pit, drinking strong tea and listening to stories about their pilgrimage to Mecca.

The next morning, we visited the mosque. This Hui village had a long history, tracing back to the early Ming Dynasty. The mosque walls were covered in paintings. The records state:

“The Hui people of Luxi County came to Yunnan with Mu Ying during the Ming Dynasty. Due to their military merits, they were granted official positions and later settled in Luxi’s Que Li Shu. They mainly reside in Baishui Town, distributed across several villages.”

Early the next day, we visited the famous reservoir. On the way back, we stopped at a rural middle school to wash off the mud that had splattered onto us and our bicycles.

From there, the road to town was a steep downhill descent, with 18 hairpin turns. We hurtled down like mad.

Li Rui sat behind me, clutching me tightly.

Thinking back now—it was terrifying. Just a single bicycle. Were the brakes even working? What were we thinking, flying down that mountain? If we had crashed, we would have died. Not just me, but little Li Rui too.

6

Less than two years later, I left the geology team to pursue graduate studies. I was going to see my Alili again! We would finally be together!

Leaving Ms. Kou was difficult—I felt a deep sadness.

But three years of graduate school took me too far away for too long. My Alili married someone else. Ms. Kou married my roommate—the one obsessed with semiconductors. They had children but, as I later heard, were not happy.

For years, I often thought of Alili and of Ms. Kou, whom I had shared a past life with. But as time passed, they faded from my memory.

Yet the one I had once overlooked—the one I had barely thought about—Li Rui—came to my mind more and more frequently.

7

What was I chasing back then? I didn’t know at the time, and I still can’t say for sure now. My mind was filled with dreams—what kind of dreams, exactly? I don’t remember anymore.

Did I dislike the geology team? Did I not want to stay in the mountains? Did I want to leave? Not entirely. If I didn’t like it there, it wouldn’t have been because the mountains were too vast or the place too remote. And if I did like it, it wouldn’t have been because of the mountains’ vastness or the remoteness of the place either.

I had seriously considered it—settling down, getting married right there at the geology team. There would have been nothing wrong with that. Spending a lifetime in the mountains wouldn’t have been a bad thing.

Did I long for the provincial capital? Not exactly. I hadn’t grown up there; I had no deep attachment to it. Perhaps this was what life in the city was for someone like me, who had not grown up there—walking down long avenues lined with sycamore trees, the glow of city lights, strangers passing by, brushing shoulders, never having met before, nothing to remember, never to cross paths again.

That was the city. Was that its allure for me? Maybe. Maybe not.

I loved Alili, but did I really want to build a life with her? At times, I thought I did. My Alili—so beautiful, so delicate. She lived in the provincial capital, in a respectable home, with a respectable job. We were well-matched. Wouldn’t that have been ideal? Was that what I wanted? Not entirely. But it was a dream I clung to, a dream that burned brightly.

I liked Ms. Kou. Every time I thought of her, a warmth rose in my chest. She indulged me, spoiled me, cared for me—I knew that. With her, I could do as I pleased, and she would always be understanding. In front of her, I never felt uneasy. Her boyfriend—the one from Nie Er’s family—eventually broke up with her. Anyone who saw us together would have thought, “They ain’t just friends.”

If that were true, then why? Why was there always a distant place—an inexplicable, unreachable place—calling out to me?

8

But there was one person—someone I overlooked at the time, someone I never really gave much thought to, never took seriously, and eventually forgot for a long, long time—who now returns to my mind again and again.

That person was Li Rui, my little Li Rui. She was sixteen, thin as a twig, with a short ponytail tied tightly at the back of her head.

Where did I lose that thermos she gave me? And when I complained—so thoughtlessly—about how terrible her bicycle was, how did she feel in that moment? Why was I so dense, so unfeeling, so crude?

Every day, as I drive to work—Genesis Road, 540, Mill Road, then finally turning onto Seagull Road—I think of Li Rui.

I think of her small face, those two sunburned patches on her cheeks, the way the highland sun had reddened them. I think of her short, tight ponytail.

I think of that spring day, riding toward the Hui village. Late spring, and she was sitting behind me. When the road got too rough, when the bicycle jolted and shook, she placed her hands on my back to steady herself.

She was smart, and she was earnest—pure in a way few people are. For children from the mountains, getting into a Chinese university was never easy. How could they compete with the privileged kids from big cities? Did she get in? And if she did, was it a good university? Or just an average one? And if she didn’t—if she never left—did life swallow her whole? Did it drown out that purity in her?

When I was little, my mother worked at a hospital. Behind the hospital was a small hill, and on its slopes grew clusters of cockscomb flowers. Every morning, as soon as a flower bloomed, children would rush up from a distance to pick it.

Why? For no reason at all. Because it had bloomed, so it had to be picked. Picked and then discarded. Dropped onto the dirt, abandoned, trampled underfoot. What a sin.

I miss those days. Not because I was twenty-one then. I miss them because now, again and again, I think of that small, slight girl—the one I ignored back then. I wish time could rewind. I wish I could go back to the geology team. Not to start over. Not to relive the dreams of summers spent taking the bus to the provincial capital to see Alili.

No. I just want Li Rui to sit next to me again, and just let the summer days drift on and on, never-ending. I just want to be her listener once more. To hear her speak again—this time, with no distractions in my heart, no noise in my ears. No accordion. Just listening. Just letting her know that when she took those first timid steps into adulthood, when she spoke softly, carefully, gathering all the courage she had—She was not speaking into the void. Someone was listening. Someone heard her. I want her to know that love never goes unanswered.

Where are you now, Li Rui? How has life treated you? I only want you to know—I remember those days. And in my heart, I will never forget.