Prologue

From Lạng Sơn Church Record, Vietnam, 1953:

“Bà Lý Thục Chân, cựu y tá Bệnh viện Pháp tại Côn Minh, đến định cư tại Lạng Sơn cùng chồng là dược sĩ Nguyễn Văn Hải.”

Translation:

“Madame Lý Thục Chân, former nurse at the French Hospital in Kunming, settled in Lạng Sơn with her husband, pharmacist Nguyễn Văn Hải.”

1. Père Jean-Joseph Fenouil

Her dissertation dealt with the French role in shaping this city’s medical system—territory I was completely unfamiliar with. There was a chapter in her draft about a certain Père Jean-Joseph Fenouil, a French missionary of the M.E.P., who died in Kunming in 1907 and whose burial ground was never found. The life of this man was summed up by Lydia in her dissertation as follows:

“Jean-Joseph Fenouil, M.E.P. (1821–1907)

Jean-Joseph Fenouil was a French Catholic missionary of the Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris (M.E.P.). He was born on November 18, 1821, in Rudelle, within the Diocese of Cahors, France.

He professed into the M.E.P. on August 7, 1844, and was ordained a priest on May 29, 1847. In 1881, at the age of 59, he was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Yunnan, China. He was ordained as a bishop later that same year, on December 27, 1881, in Kong-yang.

Fenouil served as the Vicar Apostolic of Yunnan until his death on January 10, 1907, in Yunnanfu (present-day Kunming). He dedicated his life to missionary work in China and played a key role in the Catholic Church’s presence in Yunnan during the late Qing dynasty.”

I learned, through reading her draft, that Fenouil was of interest to her due to a possible link between a medical service attached to the church that was constructed under Fenouil’s supervision, and another French hospital later known to the locals as Gan-mei Hospital, which was officially taken over by the new government in 1952, with its French director and two of his Chinese nurses fleeing to Hanoi, Vietnam.

I swiped the phone closed, on which I had been reading Lydia’s dissertation draft, and cast a glance toward the room’s far corner. There she was, at the tiny table, in her undies and bra, her thick eyebrows twisted in thought, her head hunched over her laptop.

I rolled off the hotel bed, still just in my underwear, and looked out the window. It was late March. The Yuantong Hills were a soft, pleasant green. Beyond the rocky slopes of the park, a few white clouds loitered in the blue afternoon sky.

I walked over and rested a hand gently on her shoulder.

“Want to go out for a walk?” I asked. “You’ve been working since noon.”

She shook her head but didn’t say anything. I understood completely. She’d been under a lot of stress lately. Her dissertation draft was due for blind review in a few days, and there were still a number of bumps to smooth out—gaps to fill in. The deadline was looming, and she couldn’t afford to lose a moment.

“Then I’ll go by myself,” I said, lightly caressing her bare shoulders, which were dotted with a few large moles. I gave her a kiss, got dressed, and headed for the door.

2. The Hall of Heavenly King

Atour Hotel sat along the central stretch of Yuantong Street, just slightly west of the famed Yuantong Temple across the road. It was cherry blossom season. The sakura trees lining the south side of the sidewalk were in full bloom.

Standing in the street just outside the hotel, I pulled out my phone and swiped open the old map of Kunming from Lydia’s dissertation.

The map clearly showed a site labeled 天主堂 (tian-zhu-tang, or word-for-word: Heavenly King Church, the local term for Catholic churches), enclosed by Ping Zheng Street and Gaodi Lane on the east and west, and Yuantong Street and Luo Feng Street on the north and south.

That meant the church had once stood behind the hotel. Shouldn’t be too hard to find, I thought. Lydia would be pleased when she heard what I’d uncovered. All I had to do was walk a hundred meters east, turn right onto Ping Zheng Street, and head down a few blocks—the church should be on the right.

I followed the street signs and walked down Ping Zheng Street, but I didn’t find any church—or any building that resembled a church. That was odd. The street signs couldn’t be wrong. I continued along Ping Zheng until I reached Luo Feng, then turned and walked down that street. Even though I wasn’t able to find Gaodi Lane, which appeared on the old map, I had already located three of the four streets—and still, I saw no church.

I stopped a few pedestrians who looked local and old enough to remember such things, even showed them the old map. They were just as puzzled as I was about the whereabouts of the “Heavenly King Church.”

I looked toward the north end of Ping Zheng Street, where I had come from; the sun was going down. A landmark site like that church didn’t just disappear without a trace, I thought. I might have to come back tomorrow.

Before returning to the hotel, I stopped by a streetside café and bought Lydia a kale avocado milk tea.

3. A Conference

That night, we talked about a paper she was to deliver the next day at a local university. The conference was titled “Legacy of French Medical Influence on the City: Colonial Soft Power or Humanitarian Service?” It would feature several prominent figures, including the director of the French consulate in the region.

She felt anguished and mentally exhausted as she tried to go over the paper for the hundredth time. Finally, she came over and threw herself onto the bed.

“Hold me, Shane,” she muttered, her thick black hair rumpled, partially covering her face. “I’m so exhausted.”

I placed my arms around her and pulled her into a full embrace. She felt like a volcano.

Lydia had a sturdy build and very pale, almost translucent skin. Her hair was dense and dark—a thick head of black hair, a trace of fine hair above her upper lip, and soft but noticeably full growth in her armpits. She reminded me of certain Italian women—intense, private, self-contained.

She was the kind of woman who kept to herself rather than letting things out. She would sit in silence, wrestling with a snag in her thoughts—and lately, in her thesis—rather than talk it through.

When we made love, her eyes were often closed—and when the moment came and they opened wide, it was hard to tell whether she was looking at me—for she was—or at the void behind me. I’d grown so used to that gaze that if she ever looked me plainly in the eye, I’m sure I’d feel as if I were staring at a stranger.

I often wondered what it was she saw in me—why she stayed with me all these years, when for the most part, she rarely asked for my opinion. And even when she did, she never let her own opinion be changed.

Even in her deepest moans, I never felt she was telling me anything outright—about herself, about me, or about her thesis. It wasn’t just physical release; it was her way of loosening the knots in her mind, of finding a brief calm she couldn’t reach in words. The tension that drove her seemed to pour out then—not as passion alone, but as a quiet, hard-won peace.

Late at night, we went down to the hotel’s Midnight Porridge Bar for a hot snack. Over bowls of rice congee and several kinds of pickled vegetables, she talked again about her paper for the next day. She was certain that framing French medical aid as a form of colonial soft power was the right way to characterize the city’s French medical legacy.

Her eyes were bright when she spoke—those were the eyes of someone with conviction.

4. Missions Étrangères de Paris

I got up the next morning after she had already left for the conference. She had probably taken a taxi, even though the venue—the old campus of the provincial university—was within reach by mo-bike.

I walked over to the window and pulled the curtains open. It was another sunny, pleasant day. High on the hillside behind the Buddhist temple complex stood a lone traditional Chinese structure, bathed in morning light. I glanced down at Yuantong Street below—traffic was still light, a sprinkler truck was slowly passing by.

I picked up her blouse and a pair of undies from her side of the bed, and some socks from the floor. She probably wouldn’t be back until late.

I thought of the church I had tried to find the day before. I still wanted to give it another try. Lydia would be happy if I came back with something this time.

I headed straight to Ping Zheng Street. Somewhere near its middle section, I stopped. This time, instead of consulting the old map, I opened Gaode Maps—and then Baidu. In both transit and satellite mode, three of the four streets were easily identified. In fact, you could overlay a Gaode map on top of the old map from Lydia’s dissertation, and they’d match perfectly, point for point.

There could be no doubt: today’s Ping Zheng Campus of Kunming Medical University coincided with the old church compound. I froze the moment the realization hit, and my heart began to pound.

Awe-stricken, I made my way toward the gate. The medical university’s Ping Zheng entrance was just a few feet from where I stood. Several security guards stood nearby, but none stopped me. Still in that heightened mental state, I followed the most natural and logical path: the broad flight of steps leading up the hill to a six-story instructional building that loomed at the top.

At the summit, I took a quick walk around. For a moment, I was somewhat disappointed. The six-story building seemed to be the only structure up here—surrounded by a small garden in front, basketball courts in the rear, and dormitories off to one side. If this was a university campus (which it was), it was a modest one.

More troubling: I couldn’t see anything that even faintly resembled the remains of a church—no graveyard, no clergy quarters, certainly no attached school or clinic.

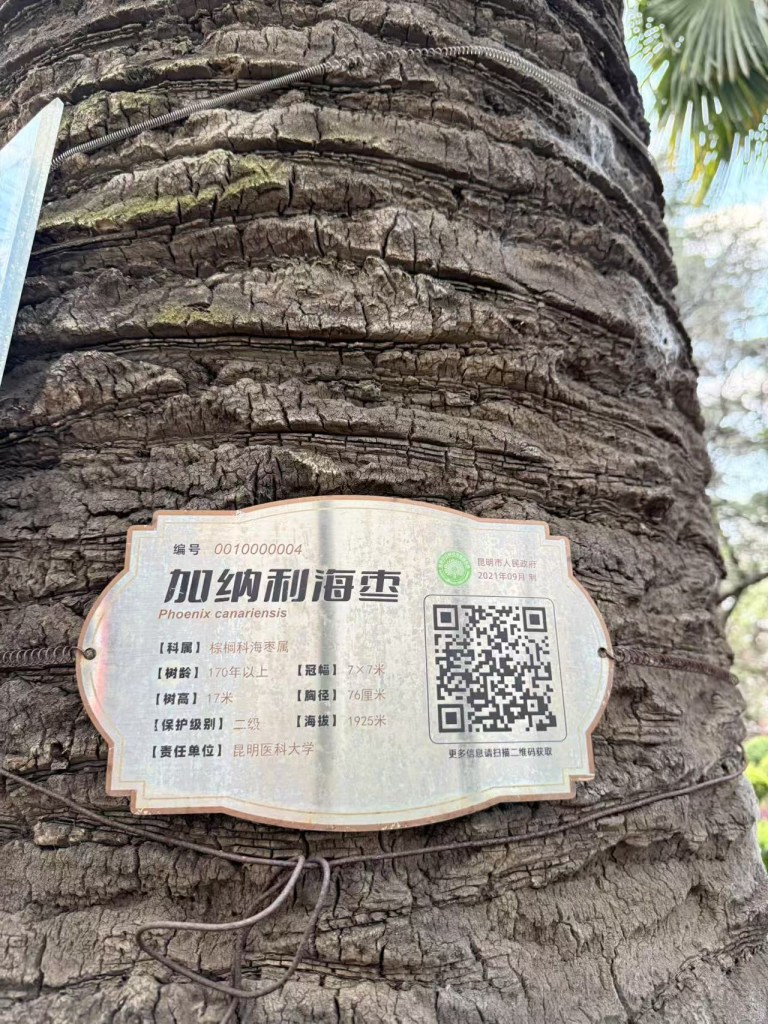

But then I saw a placard on one of the tall palm trees in the small garden in front of the building. It had been issued by the municipal government of Kunming in 2021. It read:

Phoenix canariensis — Age: 170+ years.

That caught my attention. If construction of the church began in 1883, and I was standing there in 2025, then this tree must have been planted before the church itself. That was a real clue.

I ran a DeepSeek search. It confirmed that the Ping Zheng Campus of Kunming Medical University stood on the site of the old church and suggested three things to look for and verify: an old palm tree, an old ginkgo tree by the campus entrance, and a segment of the campus wall built with bricks from the original church. Both the palm and the ginkgo trees, it said, had been planted earlier than or around the time of the church’s construction.

That’s one down, two to go. I headed back down the hill. At the bottom, beside the small guard shed, I spotted an old tree. There was no mistaking it—it was a ginkgo, and a very old one at that. A scaffold had been built around it for support. The sight hit me like lightning.

I turned my head and looked back up toward the instructional building on top of the hill. I couldn’t help but feel dumbstruck.

So it was all true. At one point—not so long ago—standing where that concrete structure now stood was a Catholic church, built during the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty by the Missions Étrangères de Paris. And it was Bishop Jean-Joseph Fenouil who had overseen its construction. And that church, later known as the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church (also called the Kunming Catholic Church), had served as the cathedral of the Diocese of Yunnan.

I couldn’t wait to tell Lydia what I had found.

5. Atour Hotel

At night, Yuantong Street was a tranquil, almost enchanted place. The crowds that filled it during the day had dispersed, and the sakura trees—finally left alone by their admirers and the flash of phone cameras—seemed able to breathe again.

I stepped into a 7-Eleven on the corner, picked up a bottle of wine and several packs of Durex, and set them on the counter. The cashier quickly scanned the items. While waiting, I checked my phone. Lydia was still out.

I returned to the hotel, but instead of going back up to our room on the fifth floor, I found a quiet corner in the lobby and sat down. A service woman promptly brought me a cup of tea.

While waiting for Lydia, I flipped through the hotel’s marketing brochure. It told a story about how the hotel got its name—from a remote mountain village the founder had once visited. True or not, I thought it made for a good story. My own take was a little different. The first time I saw the hotel’s name, I immediately thought of the word ‘attour’—and then of those famous lines from G. C., The Romaunt of the Rose:

“She was not of religioun

Nor I nell make mencioun

Nor of robe, nor of tresour

Of broche, neithir of hir riche attour.”

For whatever reason, these lines struck me as a fitting description of Lydia, even though I knew full well she was the opposite in every way. As I was musing on those lines, I saw Lydia’s tall figure appear through the hotel’s front door. She was in a black dress suit, shoulders squared, her dark hair tied back in a ponytail. I stood up and walked toward her.

6. Three Maps

One of the things the conference helped Lydia realize was that more work was needed on the section of her draft dealing with the origin of the French hospital known locally as Gan-mei Yiyuan (“Gan-mei Hospital”). Lydia maintained that Gan-mei had been a French government-funded institution from the colonial era, and that it was connected to the construction of the Yunnan–Vietnam Railway (Chemin de fer de l’Indochine au Yunnan). She also believed the hospital had always been located at its current site.

Several conference participants, however, expressed skepticism about her claims.

Though still feeling energized from being among her colleagues, Lydia was clearly unsettled by the doubts they had raised.

We were both leaning against the head of the bed. I took the glass of wine from the nightstand and handed it to her. She took a sip. The prominent areolae around her nipples made her already pale skin seem even fairer. I could tell her thoughts had already drifted back to her dissertation. Only two days remained before the submission deadline.

“What’s the plan for tomorrow?” I asked.

“I still think my thesis holds,” Lydia said. “But there are a few leads I need to chase down. I’m taking a trip to the provincial archives tomorrow.”

She reached over me, trying to grab her phone from the nightstand. I picked it up and handed it to her. She swiped it open and started scrolling through her photos. I caught a glimpse of several group shots, and one with just Lydia and another person.

“That’s the general director of the French consulate I met today,” she said quickly, before swiping past. “What I want to show you is this.”

She handed me the phone for a better look. It showed a photo listing three archival addresses where maps related to the disputed original location of Gan-mei Hospital were held.

Of the three maps, one was a 1912 survey by the Governor-General of French Indochina, titled Plan des concessions françaises et établissements à Kunming; another was a 1937 map produced by the Yunnan Army Survey Bureau; and the third, a 1945 operational map titled Kunming City Plan, was made by the U.S. Army Map Service. All three identified a French medical facility on what they called “Ping Zheng Street.” The first labeled it Hôpital Français; the second marked the name “Gan-mei” clearly; and the U.S. Army map referred to the site as “French Mission Hospital”—again suggesting a tie to the Catholic church.

The implication for Lydia’s thesis was obvious: if Gan-mei Hospital had once stood on Ping Zheng Street, then its current site on Xünjin Street could not have been its original location. That undermined her claim that Gan-mei was established and funded by the French government and had always stood where it does now.

I noticed one of the archives listed in the photo was right here in the city—Yunnan Provincial Archives (Document No. YNSA-1937-MAP-045)—and only required a letter of introduction for in-person access. Lydia had already secured the letter she needed to view that map while at the conference.

I handed the phone back to Lydia.

“Tomorrow’s going to be a busy day,” she sighed, leaning her head lightly against my shoulder. “I need to see that map, and see if I can get remote access to the other two items. I just hope it doesn’t give me any more headaches. I only have two more days left.”

She set down her wine glass and got off the bed to head to the shower.

7. At the Archives

The next morning, Lydia and I headed to the provincial archives on a mo-bike. It took us just 25 minutes. She said she might be there for a while, so I told her I’d walk around and see a bit of the city. I kissed her goodbye and wished her good luck.

But as I watched her disappear behind the front entrance of the archives building, I had a feeling the trip might prove disappointing—and that thought depressed me.

I might be a novice on this subject, but based on what I’d read in her dissertation draft, and what I’d managed to glean over the past couple of days, I had the sense that the view she was arguing against had some pretty strong evidence behind it—though perhaps not evidence in the strict academic sense, as Lydia was prone to say.

To my layman’s mind, early missionary work in places like this was rarely, if ever, just the construction of a church. It almost always came with other services—schools, infirmaries, hospitals. So it seemed entirely possible that Gan-mei Hospital might have had missionary roots. If not the institution as it came to be known in later decades, then at least in its earliest form—in terms of its facilities, its personnel.

Why did I say that? The evidence was in some of the archival photos she’d shown me on her phone. In particular, the 1937 map, made by the Yunnan Army Survey Bureau, would be a tough one to dismiss without some serious effort. The Chinese label for the midsection of Ping Zheng Street was “甘美医院,” and the French title beneath it—in smaller type—read “Hôpital Français.” That strongly suggested that the current location of the hospital on Xünjin Street was not its original site.

So there was credible evidence linking the beginnings of Gan-mei Hospital—if not in name, then in origin—to the church compound where Bishop Fenouil’s cathedral had once stood. A result of church influence, not solely colonial government policy?

As soon as the idea crossed my mind, I knew it wasn’t something Lydia would want to hear.

It was still early. I felt an urge to go have a look at Gan-mei Hospital on Xünjin Street.

8. Lazily the Pan Long Flows By

The city of Kunming once had walls and a moat. The eastern portion of that old moat was formed by the Pan Long River—literally, the “Coiling Dragon”—a charming natural waterway that drained, and still does, into Lake Dianchi.

The hospital’s official name is now the First People’s Hospital of Kunming. Though greatly expanded and modern in every sense of the word, its center of gravity still lay in the old Gan-mei Hospital compound.

Not far from the river, tucked away in a grove of tall, aging trees, stood the old South Station—the final stop of the French-built China–Vietnam Railway on the Chinese side. The original station building still stood, repurposed into a fine dining restaurant. Beside it, a short segment of meter-gauge track had been preserved as a sentimental relic.

Standing on the city-side bank of the Pan Long River, with the hospital’s sleek new buildings on one side and the weathered riverbank still bearing the texture of the past, I felt a quiet, overwhelming sense of time’s passage—of how much had changed, and how much quietly remained. The city had moved forward, yes, but traces of the old world still lingered in the corners, half-forgotten and undisturbed.

On the internet, I came across an old photo of Gan-mei Hospital, circa late 1940s, along with a group portrait of the hospital staff from around the same time.

I wondered if the building in the photo was still standing. It didn’t take much effort to find out—it had been designated a protected heritage site, with clear signage to guide visitors.

Decades of weather and foot traffic had worn the stone steps smooth and pale. I picked my way up slowly, as if trying not to wake someone sleeping. My footsteps echoed in the hallway. Locked doors and empty corridors gave the place the feel of a preserved exhibit—something you weren’t meant to touch.

At the stairwell, just as I was about to go up, I noticed a smaller set of stairs leading down—to what looked like a cellar entrance. I hesitated for a moment, then continued on.

9. Docteur Beffante

On the copy of the group photo I saw, the handwritten Chinese characters “白蕃特” were marked beside a tall, gaunt figure at the center of the image. An “X” had been drawn over his chest. That man was Louis Beffante, the last French director of Gan-mei Hospital before its takeover by the People’s Republic. Apparently,白蕃特 was how Louis Beffante was known—by his Chinese patients, colleagues, and even his detractors.

Lydia had devoted a chapter in her dissertation draft to Louis Beffante, taking on some of the controversies that surrounded the Frenchman. Her summary of Dr. Beffante’s biography read as follows:

A Biographical Record of Dr. Louis Beffante (白蕃特), Compiled from archival sources in France, Vietnam, and China:

Dr. Louis Beffante (1902–1987)

Born in Ajaccio, Corsica, to an Italian family (originally Buffanti), Dr. Louis Beffante trained in tropical medicine and made his mark early with a thesis on North African malaria that earned him a Paris Medical Faculty award.

He spent over two decades in Asia, first in French Indochina, where he founded Vietnam’s first parasitology lab, collaborated with famed plague researcher Alexandre Yersin, and treated Allied POWs during the war. In 1946, he was sent to Kunming by the Missions Étrangères de Paris to direct Gan-mei Hospital. There, he introduced DDT to combat malaria and oversaw leprosy treatment efforts—until rising political tensions forced his hand.

Refusing to cede control of the hospital to the new Communist authorities, he smuggled out medical records and, in 1952, fled China with two Chinese nurses. They were briefly captured by Viet Minh guerrillas and released only after a ransom was paid in gold.

Beffante spent his later years in Marseille and Corsica, running a free clinic for immigrants and recording memories of opium treatment protocols once used at Gan-mei. He died in 1987. His grave bears the Chinese characters “仁心” (“Benevolent Heart”), carved to honor the wishes of the two nurses who had escaped China with him.

Lydia’s unsympathetic assessment of Beffante was in keeping with the general position she had taken in her dissertation, though to me it felt a bit harsh.

10. Two Nurses and One Doctor

It had only been a little more than half a day, but I already began to miss Lydia—and miss her terribly. When she called, I took the first taxi that answered my hail and headed back to the Archives.

Lydia was already outside, standing on the street just beyond the Archives’ front entrance. She had one hand on her shoulder purse, the other hanging loosely by her side. Maybe it was because she was always a bit taller than her peers, or because her shoulders lacked that soft, rounded shape people expect in a woman. Maybe it was her gait, or a certain stiffness in her posture. Whatever the reason, she was someone you noticed—not because she stood out, but because she didn’t quite fit in. And then there was that unhurried, slightly puzzled look on her face—a look I always associated with her. A stream of warmth rose in my chest.

I got out of the taxi, walked up to her, and held her for a brief moment. We started to walk, not thinking about where we were going. But after a while, she stopped.

“Shane, I’m hungry.” She took hold of my arm. “I haven’t eaten since morning.”

There was a 7-Eleven at the street corner. We bought a sandwich and brought it to a nearby park. There were kids playing soccer on the lawn.

I told her about my trip to Gan-mei Hospital. She didn’t seem particularly impressed, and I could see why. She had a whole chapter about it—there was little I could tell her that she didn’t already know. She was also familiar with the group photo. What did trouble her, though, was the map at the archives she had been able to study. Still, she was convinced she could make her theory hold.

The fact that the name Gan-mei appeared on a map showing a location on Ping Zheng Street, she argued, could be a coincidence—you couldn’t rely on names alone. Context mattered. A hospital the size of Gan-mei in the 1940s, with directors appointed not by the Church but by the government or government-affiliated agencies, could only be explained if it was indeed a government-run medical institution. I thought those were valid points.

As she spoke, a loose ball from the kids’ game rolled our way. I picked it up and threw it back to them.

That night, after we got back to the hotel, she immediately got down to work. The issues raised by the archival materials she had reviewed needed to be addressed—even if only as a preemptive measure—to defuse any potential objections to the thesis she had developed.

For a while, I sat on the bed, unsure of what to do. Then I thought of the group photo and felt an urge to take another look. In her summary bio of Dr. Beffante, Lydia had mentioned that he “fled China with two Chinese nurses” in 1952. I wondered if the two might be among the staff in that photo.

There was one woman in the front row, one person away from Beffante, but she looked older, and it was hard to tell her ethnicity from the image. The two rows of women in the back appeared to be lower-ranking nurses—unlikely to be the ones selected for evacuation.

But just to Beffante’s right, in the second and third rows, stood two young Chinese women in black robes—distinct from the white uniforms worn by the nurses in the back rows. Why were they positioned so close to him, while the others were relegated to the rear? Could the black robes have marked them as senior staff—or hinted at some special connection to the church?

I did some digging online while Lydia was working on her draft and came across a few things I found interesting.

In the document “Rapatriement du personnel médical français, Yunnan 1952,” held at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nantes Archives (Fonds de Nantes), there is the note:

“Dr. Beffante quitte Kunming le 15/04/1952 via Hanoi, avec 2 caisses d’archives médicales.”

In English: “Beffante left Kunming on April 15, 1952 via Hanoi, carrying two boxes of medical archives.”

Some sources also hinted at the existence of a farewell photo, said to be housed in the Vietnam National Archives. It was believed to have been taken before the evacuation in 1952. The description from the Vietnam National Archives (TTLTQG-III) read as follows:

“In April 1952, staff of the French Hospital in Kunming bid farewell at the Red River Wharf.

Third from the left: Beffante, holding a cane.

Far right: Li Shuzhen, holding a French Bible in her arms. Second from the right: Zhang Huifang, carrying a medical case (inside was the hospital’s official seal).”

This was absolutely fascinating stuff, and I wondered why Lydia had made no mention of it. I raised my head and looked at her—she looked serious. She must have had her reasons for leaving out such details. After all, she was the expert. I chose not to bother her.

11. Lydia’s Big Day

The next day was Lydia’s last day. She had to submit her dissertation draft for blind review by midnight. We were staying put in the hotel room and going nowhere. It was going to be a race against time.

Lydia had worked out a response to potential objections to her view, and had incorporated it into her draft. It read well, and I felt that it worked quite well also in lessening the impact of the three maps.

We discussed the matter some more during her lunch break. By late afternoon, Lydia began to have doubts again—possibly from overwork and stress. I urged her to take a break, maybe go out for a walk. She refused, but came over to me and asked me to hold her. I saw tears in her eyes. But she got better after a while, stood up, and returned to her desk.

From the window, I watched the sun go down. The twilight in the western sky was spectacular. But even that faded, and the day was over.

“Lydia,” I said, “it doesn’t have to be exactly midnight. A few more hours won’t make a difference. You’re good to go.”

She didn’t listen at first. Her eyes were fixed on her laptop screen. I walked over to her. She was scrolling back and forth through her draft, then back again.

“Are you sure it’s alright?” she asked, wanting my reassurance, even though she knew full well it was time—to upload the file and click Submit. But she couldn’t bring herself to do it. “Do you think I’m ready?”

“Yes, Lydia,” I said. “You’re more than ready. Upload the file, and click Submit.”

And just like that, she did—with her heart in her throat and her hands trembling. But she did it.

And just like that, the ordeal was over.

12. An Amateur Historian

I wasn’t an academic myself, and there were things scholars and professors did that I simply couldn’t make sense of. Take my Lydia, for example. She wrote a long essay, mustering an impressive array of facts to support her argument, yet left out things a layman like me found interesting. She could dismiss, or remain unmoved by, details I felt I couldn’t ignore.

It’s been several days now since she submitted her dissertation. She talked as if everything she had collected and wrestled with was already in the past—as if the dissertation itself were behind her, and she was eager to move on to other things. She smiled more, became more open. Sometimes I felt I was seeing a new person—or at the very least, a side of her I hadn’t known before.

The problem now was me. While Lydia was relieved to have moved on, I wasn’t ready to let go. On the contrary, I felt the real story hadn’t been told yet, that the project had only just begun. There were genuinely interesting things she hadn’t explored in her dissertation but were worth finding out—like the real stories of Beffante’s two nurses. What happened to them? What was their fate after the Frenchman abandoned them in a foreign country but himself returned to France?

It felt almost ironic: just as Lydia was ready to move on from the subject that had consumed her for the past five years, I was only beginning to get drawn into it.

With a bit of luck and some tenacity, I managed to gather enough material to piece together a short biography of one of the nurses. I showed it to Lydia. She thought I did a good job—but wasn’t particularly interested in it herself.

What follows is the report I showed her: the story of one of the two nurses, as best as I could reconstruct it from my research. I never imagined I’d become a historian myself—not a professional one like my Lydia, but an amateur. Still, writing it gave me real joy. It also made me a little sad.

In any case, here it is. And if you will, dear reader, judge tenderly of me.

The Vanishing Life of Li Shuzhen

Long before her name changed and her passport stamped another country, Li Shuzhen was simply the tall girl in a white apron who spoke French in the corridors of Kunming’s Gan-mei Hospital. She was born sometime in the mid-1920s—nobody wrote the exact year down. By 1948, at barely twenty-three, she had already mastered obstetric suturing and enough conversational French to impress Dr. Louis Beffante, the hospital’s new director. He hired her on 15 April 1948, noting in her file that she was “quick, unflinching, and fluent.”

In those years Kunming was a crossroads of armies and epidemics. When a fierce malaria wave hit in 1950 and quinine ran out, Nurse Li improvised—soaking cotton in alcohol and pressing it onto children’s wrists and temples to pull down fevers. The trick worked often enough to earn her a footnote in the Yunnan Medical Techniques Compendium and Beffante’s respect. By 1951, she held a coveted key to the hospital’s opium cabinet—a privilege granted, the record insists, “under nun’s supervision.”

But war was tightening around them. American intelligence files note that “Nurse Li (codename Rose) regularly supplies the French consulate with medical-supply inventories.” Maybe she was helping. Maybe she was just translating requisitions. Either way, she was chosen as one of two nurses to follow Beffante when he fled in April 1952.

They crossed the border at Lào Cai, down to Hanoi’s St. Paul Hospital. There Li Shuzhen became Lý Thục Trinh, married a soft-spoken Vietnamese pharmacist named Nguyễn Văn Hải, and tried to stitch a new life together. She trained midwives at the Franco-Vietnamese Hospital until a “cross-border credential dispute” in 1956 stripped her of her license. After that, the official files thin out—just a few grim lines in the Agent Orange Victims Registry: “Lý Thục Trinh, formerly Chinese midwife, liver cancer, 1968, age ≈ 43.”

Even death didn’t settle the rumors. A French military dossier brands her an informant; Vietnamese security notes say she was under surveillance; a Chinese report from 1960 labels her case “history pending investigation.” Neighborhood gossip in Hanoi lends a softer image: an elderly neighbor remembered “that Chinese woman who burned letters at night—little bits of French songs drifting up in the ash.”

Tiny relics keep her story breathing. A pair of gilded forceps—engraved “LB à SZ 1951”—sits behind glass in the War Remnants Museum. A black-and-white photo taken at Red River Wharf shows her clutching a French Bible as she boards the evacuation boat, Beffante a few steps away with his cane. And somewhere in Ho Chi Minh City a middle-aged grandson named Nguyễn Louis keeps a faded copy of his Kunming grandma’s nurse’s certificate in a desk drawer.

[Author’s note 1]

In my imagination, she always carried a pressed ginkgo leaf from Kunming—its veins stained in the colors of the French flag—a secret keepsake from two worlds she never fully belonged to. A woman crushed by history deserves more than a line in an archive; she deserves the breath of story, the ache of remembrance, and a final farewell on the Red River.

[Author’s note 2]

My heart told me the young woman immediately to Beffante’s right was Li Shu-zhen, and the one just behind him was Zhang Hui-fang. It would take heaven and earth for anyone to change my mind.

Epilogue

Lydia and I left Kunming in separate ways. We each got busy with our work. Meanwhile, her dissertation passed blind review. Soon after, she successfully defended her thesis, earned her Ph.D., and took a job at a 8507 university. Our correspondence gradually thinned. Less than a year after we left Kunming, we ended our relationship. But I remain grateful to her—for sharing a portion of her life with me, and for taking me on an intellectual journey from which I learned so much.