“μέχρι τέλους μὴ προσαγορεύειν μακάριον· πρὸς γὰρ τὸ τέλος σκοπεῖν δεῖ τὸν βίον.”

“Call no man happy until he is dead; for only then can the story of his life be judged complete.”

—Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

1

About ten years ago, in 2040—back when people said I had been long dead—memories of a conference on well-being in Shanghai came back to life. Dining alone in the ghostly hotel restaurant late that evening, after finishing registration, I saw a woman enter, glancing around as if looking for someone. She was about forty, dressed in a well-cut suit that flattered her figure. The badge on her jacket marked her as a conference participant—or perhaps an organizer; I couldn’t tell.

There was something familiar about her, though I couldn’t place it at first. Then I remembered. Five years earlier, I had met her at a similar conference at Washington University in St. Louis—a ghost of a town, in even worse shape than when I had last been there—as a poor graduate student attending a conference, sharing a hotel room with half a dozen equally poor graduate students.

And when was that? I asked myself. Back when The Andy Griffith Show and Sanford & Son were still on major networks, years before the big boss in the White House poked a Jewish woman in her private parts with a cigar.

Almost at the same moment, she recognized me too and began walking toward my table.

“How have you been!” I stood, shook her hand politely, and invited her to join me for coffee. She hesitated, then agreed. I signaled the waiter and ordered ice cream for her.

So, no, she wasn’t one of the speakers at the conference, but she would be attending the talks. I brought up the conference in St. Louis.

“Ah, yes,” she said, a smile lighting her face. “The Blue Moon Hotel—I remember that well!”

She even remembered the title of my talk from that occasion and showed me a snapshot she had taken of me. She said she had enjoyed that talk and thought I was convincing. All of this was new to me.

“You’re too kind,” I said, feeling a little embarrassed. I thought then of the noisy rooftop bar at the Blue Moon, where her only drink had been tonic water, and of the spicy chips we’d shared at a Mexican restaurant on Washington Avenue. She had always been the unassuming one, preferring the background to the spotlight.

There was something about her—poised, alluring in that quiet way, something that made me want to touch her. Not what you think—or perhaps exactly that; I was confused about her back then, as I am now. And besides, I was supposed to be long dead, remembering all this through some god-knows-what medium. For what else would you expect to hear at a conference on well-being, if not debates about whether dead people had lived lives of eudaemonia—lives they might not even have lived at all?

She stood, apologizing that she couldn’t stay, but promised she’d come to my talk. I watched her walk toward the exit until she disappeared behind the screen. Her smile stayed with me for a long while; I couldn’t get her out of my head.

2

I remembered being back in my hotel room—remembered pouring myself a glass of wine, switching on the reading light, and stretching out on the bed, soon drifting into thought.

Happiness, the master of the subject tells us in the Nicomachean Ethics, is not something we seek for the sake of something else. We don’t pursue happiness to make money, for instance, and we don’t chase it just to become famous. It would be funny, I thought, if someone actually tried that.

I also thought it was funny when people say, “You can’t buy happiness, but you can buy BBQ.” Not sure Aristotle would have agreed. The master gives us at least one clear test: if what you call “happiness” depends on things external to you—things you can’t control—then it isn’t true happiness. Maybe eating BBQ makes you happy, but since BBQ can be taken away, eating it can’t be what happiness really is.

But happiness is such a slippery thing that even the master sometimes drifts into incoherence. Take one of his more puzzling claims: that things happening after you die can still affect your well-being—lowering it if they’re bad, raising it if they’re good. What did he have in mind? A sandcastle I built before I died—one I did build—washed away after I was gone? Or something grander, like the Hellenistic empire his pupil Alexander the Great built in his lifetime, only to crumble after his death? How, exactly, does an event like that alter his eudaemonia?

I thought of the friend I had chanced upon that evening in the restaurant, whom I had first met years ago in a foreign land—foreign to her, or to me; who’s to say? What would she make of all this? She was an economist, not a philosopher like me, but it would be nice to hear what she thought. The likes of me think in words; she, in numbers. But that shouldn’t be a barrier.

3

She came in just before the first morning session was about to start. I gestured to her, pointing at the empty seat next to me. She came over, a tiny paper cup of tea in hand, and sat down. Seeing I was empty-handed, she passed me her copy of the conference program to look at.

I glanced through it quickly, then handed it back to her. At that moment, a young girl—she looked like a student or maybe one of the office staff—moved quietly through the rows, body lowered, arms close to her sides, trying not to attract attention. She tiptoed up to her. They exchanged a few whispered words. I overheard the girl address her as “dean.” She was the dean of the college—I hadn’t known that. But I was happy to find out, and happy for her, though I couldn’t explain to myself why. Years ago in Michigan, I once overheard some faculty chitchat: “Once you’ve been a dean, you can never go back to teaching.” Why that was, I had no idea either. Perhaps she could answer it for me.

Thus began the conference.

Give me a life, and I can chop it up to order—as a sum of units measured in seconds, minutes, days, months, or years. The customer is God. Want life measured in minutes or days? Not a problem. Prefer months or years? Also not a problem.

At the end of the day, whatever temporal units you use to measure a life can always be mapped onto spatial points—locations arranged in sequence to match those units. Whatever happens in one of these locations—past, present, or future—can be yanked out of its original place and inserted into another, and it wouldn’t matter much.

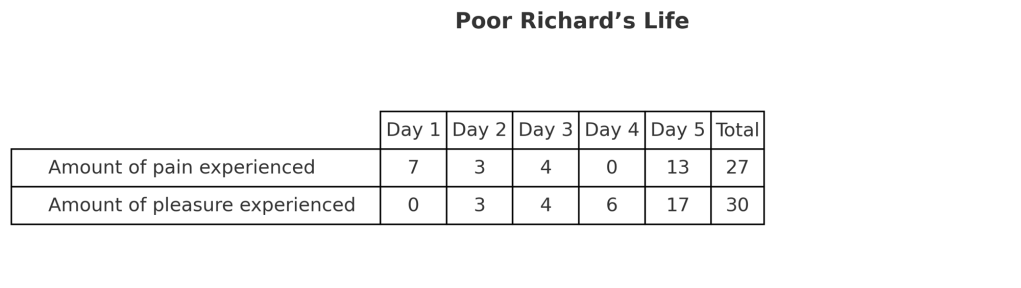

Take pain, for example. Suppose the pain you experience over five consecutive days is represented by the following diagram:

Whichever way you count it, the total pain over those five days adds up to 27 and 30 for pleasure. Shuffle the pain around however you like—the sum won’t change. ditto for pleasure.

Define a “bad day” as one in which you experience more pain than pleasure, and a “good day” as one in which the opposite is true. If a life can be shrunk to a single day, then your life sucked if the former is true, and you were blessed if the latter is.

4

During the lunch break she took me to her office for tea. The office was small, but all the insignia of a school dean were there—the placard on the desk, the neat stacks of papers that looked like official files.

I told her, half-joking, that for a dean the office was modest.

“We’re in the process of moving to a new building,” she said with a smile. “It should be more spacious on your next visit.”

She asked me to sit next to her on the small couch, and I did. I watched as she brewed the tea. When it was ready, she poured me a cup. We took a sip.

Again I wondered what it was about her that gave me that feeling of familiarity, that sense of intimacy—as if we had known each other all along. There was a riddle of a smile on her face, one whose meaning could never be fully fathomed.

We sipped our tea. A moment came, then slipped away; another ticked past and was gone. For a long while, nothing happened. We said nothing, and did nothing.

Presently, she glanced at her phone and stood. “The afternoon session is about to start soon,” she said. “We should be on our way.”

5

There was no particular reason I could think of why my talk had been placed last in the conference program. In any case, it was now my turn. I walked up to the podium, fully aware that all eyes were on me—among them, my dear Dean’s.

I glanced at the audience and caught her gaze; her expression was serious, but expectant. I thought of the moment we had spent in her office during the lunch break, of the tea she had brewed and served while sitting next to me on the couch, and I thought of the album.

I was ready.

I had long held the view that an event’s impact on your well-being depends on its timing. To suffer an injury at five may not be as bad as suffering the same injury at twenty-five; winning a million-dollar lottery at thirty is not the same as winning it at six. Why does timing matter? I could only think of one explanation: for most of us, a human life has a narrative structure, and the well-being significance of an event depends on the juncture of the story in which it occurs. A million dollars means much more when your career is just beginning than when you are a child.

When I speak of a narrative structure to human life, I do not mean it is something innate—like your heart or the amygdala in your brain stem, something you are simply born with. What I mean is that humans are planning agents once they reach the age of reason. You can argue over whether that age arrives earlier or later, but it arrives, sooner or later.

The planning ability I’m talking about doesn’t have to be extraordinary. For most people, it’s as basic as planning to start a family, raise a few kids, and care for one’s parents when they are old.

Supporters of objectivism about well-being, however, implicitly treat moments, periods, or even long stretches of life as if they were spatial locations. Events happen in these “locations,” and a location is bad if the bad events in it outnumber the good. A life is tragic, by this view, if it contains more bad events than good ones.

But if the objectivists were right, it would be hard to explain why the timing of identical events makes such a difference. If a life is merely a collection of spatial locations in which events—good or bad—happen, why should the same pain in one “location” feel so much worse than in another?

At that point, someone raised a hand.

“Yes, please!” I said, gesturing for them to speak.

“The notion of narrative structure is a useful one,” the person began. “But it can’t be the whole story. It doesn’t, for example, explain diminishing marginal utility. The first cup of morning coffee gives great pleasure, but the pleasure diminishes with each subsequent cup. Narrative structure has nothing to do with that. The cups of coffee you drink—you drink them in a series, one at t1, the next at t2, and so on.

“Not just coffee—many things we do, and many things that happen to us, work in the same way. In this sense, well-being is additive: you can sum it across time, adding up the good, subtracting the bad, and arriving at a number—call it “units of well-being,” call it “utilitae,” or what you like. The point is, in one important respect, well-being can be calculated without reference to the narrative structure of a life.”

I nodded. “Duality is the human condition; we count our days in numbers, but we live them in stories.”

At that moment, I saw a twinkle in her eyes.

6

The banquet that evening was splendid, but unusually—and agonizingly—long. A light atmosphere of celebration, a spirit of gaiety, permeated the air. Faces, chatter, old friends catching up, new ones opening up to each other.

She was sitting opposite me. Being the dean, and a well-respected scholar, there was no shortage of guests who wanted a word with her. She glanced my way occasionally, a longing in her eyes that only I could discern. It was an unusually warm March day. I wished I could leave—with her arm in mine—and take a stroll in the twilight.

We got out in the late hours of the night. Street lights had come on. The lanterns hanging in storefronts waved in the cool evening wind. I thought of Tokyo.

After she had thanked all the conference participants for their support in making the event a success—a milestone—and expressed her wish, on behalf of the college, to see all the distinguished guests “in the near future,” we were finally able to leave, heading in the campus direction.

I picked up her arm and held it in mine. A feeling of remoteness—in time and space—permeated my whole being, as if I had been spirited away, back to a time unfamiliar to both of us.

“Going to your hotel, or my office?” she asked as we approached the campus entrance.

“Let’s go to your office,” I said, turning toward her with a smile. Her casual remark reminded me of the tea set still lying on her table and the unfinished tea we’d left behind at lunch. I wouldn’t mind some more tea. But mostly, I wanted to be with her.

7

In the pitch darkness I couldn’t make out her face; only her breathing was audible—the faint, intangible, yet ever-present breathing of a woman. The bare, smooth floor felt cool against my back. Her kisses were unexpectedly wet, and her grip sudden and firm.

In the total darkness I kicked over a stand. It crashed to the floor with a sharp, ringing clatter, and whatever was on it—a flower pot, probably—landed with a dull thud. For a moment we stopped, and everything went quiet. Empty echoes drifted in the hallway beyond the door. Then darkness again. We embraced once more, as if the momentary pause had infused us both with renewed passion and energy.

As if being inside her, having her, wasn’t close enough, I searched for her face, her breasts, the smooth, cool silk of her bare back. I felt her all over, as if my hands were learning her by heart—so that, some future day, I might hold her again simply by shaping my hands as they moved over her now.

A light flicked on in the building across the way, then snapped off. A car’s headlights swept briefly across the curtained window before vanishing back into the night. I thought I heard a faint rumble from underground—a passing subway train beneath the building. It drew closer, closer still, then paused—as if holding its breath—before a long, sighing release. And then it faded into the night, into the darkness so thick I could not see through. And still, I held her in my arms.

8

And just like that, you walk down the station steps at University Town Station, my Eudaemonia. The tunnel walls and the arches are smooth and close around you; the steps feel never-ending. Tunnels fork off, and one fork splits again into other tunnels, as though you are walking—willingly letting yourself get lost in a labyrinth you wish would never end.

You whisper in her ear as you walk. You look her in the eye with a look only she and you understand. Your shoulder leans close to hers; both your hands hold around her soft arm, and you give her a slight lift at each step down—the way a young lover does for his girl.

All around, young college students are going up, some going down. A flock suddenly appears from a tunnel that a moment ago seemed not to exist; another group vanishes just around a corner. Echoes. A cool breeze drifts up from deep in the station. Sneakers squeak on shiny floors.

From the office building to the subway station was barely a hundred yards. You don’t need to know exactly where the station entrance is; even if I told you, you’d still miss it. This isn’t your usual neighborhood, not your usual college campus. On any given day, if you stepped out of the building and tried to spot the entrance, you’d walk right past it. There’s a bike rack here, a college canteen there, a small grove of trees, and a walled-off corner of a residential community. You get the idea. No map needed—just follow the ebb and flow of young people, college students heading to class or leaving it by subway.

And just like that, you and your love walk down the station steps. You think you’ve been walking forever; you think there can’t possibly be any more steps. And yet it feels as if you’ve only just begun—as if you’ve only taken your first few.

There was a time, long ago, when walking felt like gliding. There was a time, years ago, when you never really walked at all; you were only living a dream. Back then you were young—your gait light, your whole being vibrant, your face sun-tanned, and your eyes bright and unlined.

It is a fleeting moment. And in that moment, something familiar yet long lost—a warm feeling—quietly surges up in your heart, like an unseen, unexpected wave, like sunlight breaking through. Inside, you melt—like an ice cream sundae under the sun, or a sandcastle on the beach under a rising tide. A surge of sudden energy, a feeling of youth: your feet feel light, your whole being afloat, about to rise, like clouds—free and adrift. Gravity is no more. Time ceases.