1

I woke up groggy and a little confused. I’d heard a chime, followed by what sounded like a recorded voice apologizing for waking me, while a robotic arm gently poked me in the ribs.

Still dazed, I sat up on the edge of the bed, hands on my knees. The floor was cool beneath my feet. The room was dim, padded, and still. In the corner, I caught a glimpse of a softly humming camera.

No windows. No clocks. A room sealed in time.

A voice instructed me to pick up the recorder:

“Greetings! We hope you had a nice sleep. When you feel ready, please record your answer to this question: What do you believe is the chance that the coin landed heads and that today is Monday?”

What’s going on? I felt befuddled. What happened? I couldn’t even name the day—Not Monday, not Tuesday. No calendar date. Not even a blank wall with a number on it. Just the vague notion that a day exists—somewhere, sometime.

Where am I? Why was I being asked this?

It took a while for the fog in my head to lift. Then a thought came: someone, somewhere, had told me about a coin toss.

Yes. That was it.

Someone had said they’d toss a coin after putting me to sleep.

Memories began to return. I remembered agreeing to take part in an experiment. I remembered the scientists explaining the design, what my role was supposed to be, and the dose of dexmedetomidine I was to receive.

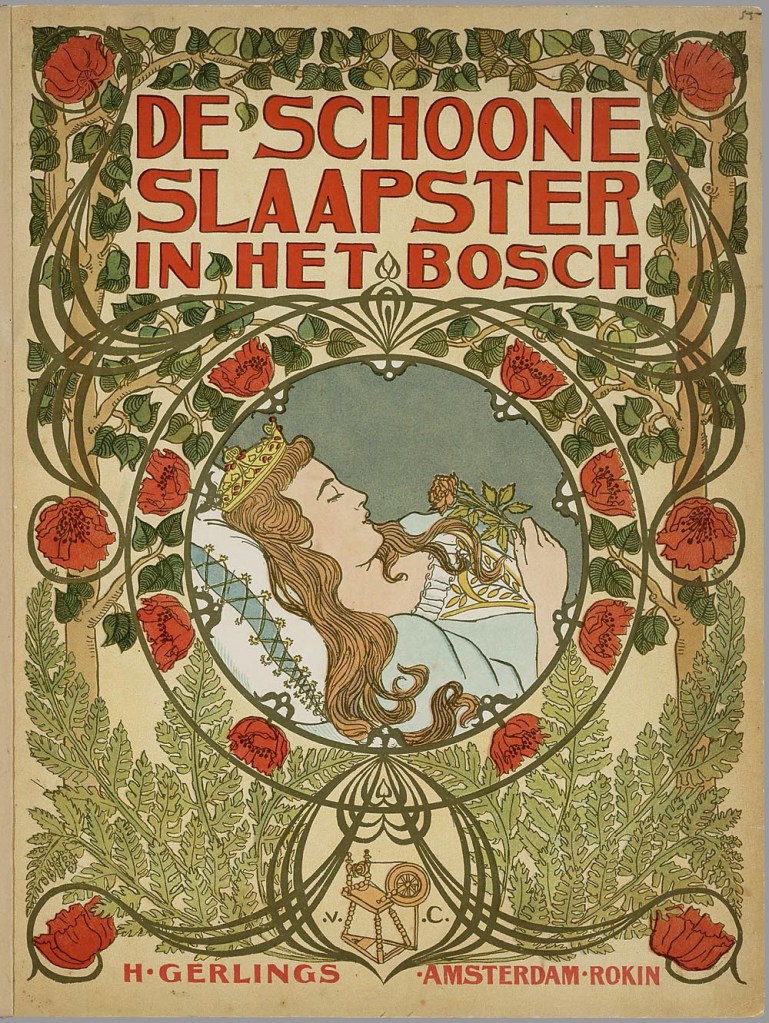

The experiment was called the Sleeping Beauty Problem, the scientists had said. They even started calling me their “Sleeping Beauty,” half-joking, as they walked me through the setup—

First, they’d put me to sleep. Then flip a fair coin.

If the coin landed heads, I’d be woken up on Monday. If it landed tails, I’d be woken up on Monday, given a pill to erase the memory, and put back to sleep—then woken again on Tuesday.

“Sleeping Beauty,” the team leader had said with a wry twinkle in her eye, “your job is simple: take a nice long sleep. When you wake, you’ll hear a voice asking you to assign a probability to the coin landing heads. Answer the question, and you’re free to go—and get paid. A nice deal, wouldn’t you say?”

My last memory before slipping into sleep was the kind face of the pharmacologist. As she pushed the dexmedetomidine through a syringe into the artery in my arm, she said softly, “You’re going to be fine.”

As I replayed all this in my head, a headache began to form. I couldn’t keep going. I had to lie back down.

Each time I opened my eyes, it felt like the experiment was just beginning. No before. No memory of ever having been awake in this room. No trace of a previous day. Only the mysterious, fleeting moments one calls “now”—and the impossible question.

“When you’re ready,” the voice repeated, “simply pick up the recorder and state your answer. A friendly reminder of the question: given your current evidence, what do you believe is the likelihood that today is Monday?”

I sat up again, my head empty. I had no evidence—none, at least, in the ordinary sense.

“I know I’m here now,” I thought, “but I have no idea where here is. And though I just said now, I have no idea what now refers to. If I knew how the coin landed, I’d know whether today is Monday. But they flipped the coin after I was put to sleep. How am I supposed to know?”

As I struggled to think, my thoughts began to drift.

2

There was once a brilliant British musicologist and conductor, a man known for his ability to play, compose, and dictate musical instructions all at once. Then a strange illness struck, and he lost almost everything—not only the ability to form new long-term memories, but also most of the memories of his past.

He became a man with no before, and no after.

Since the illness, he had kept a diary, recording each time he believed he had just woken up. The entries were painfully repetitive—urgent affirmations of presence, each one overwriting the last. A single page might read:

“8:31 AM: Now I am really, completely awake.”

“9:06 AM: Now I am perfectly, overwhelmingly awake.”

“9:34 AM: Now I am superlatively, actually awake.”

Each time, he crossed out the previous entry—convinced it had been wrong—because this new moment felt more vivid, more real, more now than any before.

I didn’t think my condition was as severe as his.

Still, if this state continued, all my future thoughts, plans, and experiences—if such things were still possible for me—would come unmoored from real time. And should that happen, then half of me—the future me—would be all but gone. I would become entirely a creature of the past.

There would quite literally be nothing to look forward to.

Not because the future held nothing worth anticipating, but because without knowing what day it was, I couldn’t even begin to reach for it. I couldn’t make plans for the coming Saturday, for example. I couldn’t look forward to seeing mon été at the airport on Sunday.

And if those things became impossible—things that could no longer happen—then they would become things that would never come to be. And if so, my memories would eventually have nothing left to be memories of.

So while I was still faring better than the musicologist, the simple fact that I didn’t know what day it was—and had to guess—gave rise to a slow, quiet kind of sadness. It threatened to dissolve me.

A thin film of self-pity settled over me, and I didn’t brush it off.

Then the voice cut in again. A dry, mechanical reminder:

“You have not yet answered the question.”

3

The prompt snapped me back. Once again, I tried to focus—tried to think. By now, I’d regained enough of my faculties to give the question serious thought.

What are the odds of this being Monday?

The answer seemed straightforward. They had assured me the coin was fair. If that were true, then the rational answer—the obvious one—was that there was a 50% chance today was Monday. And I should believe that.

Having reached this conclusion, I reached for the voice recorder. But just as I was about to speak, a thought stopped me.

I had reasoned that the chance of today being Monday was 50% by looking at it in terms of the coin toss. Heads or tails—two outcomes. Monday or Tuesday—two days. But I had overlooked another way of framing the problem: not in terms of the coin’s outcome, but in terms of the number of wakings.

The experimenters had been clear: If the coin landed heads, I’d be woken once—on Monday. If it landed tails, I’d be woken twice—once on Monday, once on Tuesday—with the first memory erased.

That made not two, but three possible wakings:

– Monday (after heads)

– Monday (after tails)

– Tuesday (after tails)

Three possible wakings. And if each waking was equally likely to be the one I was in now, then the probability that this was Monday would not be 50%, but one in three.

I set the recorder down.

I couldn’t make up my mind which of the three wakings this was. But I didn’t know how to proceed from here either. The dim lighting, the sterile stillness, the absence of anything real—it dulled my thoughts. A fog crept back in, quiet and stubborn. My mind began to blur once more.

4

I saw two lonely trees by the lake, at the end of a woodwalk, their limbs intertwined. A cool breeze was blowing in gently from the lake, but it was too little, too late for the sun-parched grass along the lakeshore path—garden cosmos, daisies, reeds, and other wild growth. It was high summer, but the intense, sad, shivering chirps of the insects in the grass made it sound as though fall had already arrived.

I saw the shadows of tall grass cast across the path and figured it must be late afternoon. I tried to imagine I was mon été, the one who had taken the photo—that it was my eyes taking in the view. The planks creaked beneath my jogging shoes. I tried to imagine that the exasperated heaving I was hearing came from her lungs, as I slowed from a brisk pace to a walk, my summer’s eyes momentarily blurred by the afternoon sun.

She had sent the photos last Wednesday—shots she took while jogging along the lake near her home. That was six days ago if the coin landed heads and today is Monday, or seven days ago if it landed tails and today is Tuesday.

I found it disturbing that a word I’d used every day had suddenly ceased to mean anything.

What day is today?

I wished I could talk to her—mon été—someone rooted in real time, someone for whom today still meant something. I wished I could hear her say, “Love, I’ll wait for you tomorrow at the house with the terracotta roof,” because while the word tomorrow might be empty when spoken by me, in her voice it meant something real.

5

Years ago—maybe ten years back—I listened to an audio narration of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men on a long flight. Somewhere in the middle of the book, Warren tells a curious tale of forbidden love from another era.

In Chapter 4, Jack Burden recounts the story of Cass Mastern, a distant ancestor. Mastern is a Confederate soldier who falls into a doomed affair with his best friend’s wife, Annabelle, while lodging with her and her husband, Duncan Trice. Wracked with guilt, Mastern tries again and again to get himself killed in battle—hoping Duncan will kill him instead. But Mastern doesn’t die. He becomes a hero. When the affair and betrayal are finally revealed, Duncan takes his own life, leaving his wedding ring under Annabelle’s pillow as a final, wordless gesture.

That story, once told, just sits there.

The family garden where the two lovers often had their rendezvous lodged itself in one’s head and wouldn’t go away—not because it was a garden, or a place where “love” took place, or anything one might typically associate with that word, but because it felt like a black-and-white photo turned brown and warped over time—an image from another century. One thinks of parasols, long gowns—the kind women once wore while taking slow, deliberate strolls with their gentlemen friends.

It’s a haunting, frozen moment—deeply emotional, yet sealed off, ambered over in a bygone Southern world.

The emotions still resonate—guilt, desire, betrayal—but everything else feels alien: the language, the tone, the color of it all. Brownish, Confederate-era, Gone with the Wind stuff. That wasn’t just memory—it was memory fossilized. Love between a man and a woman, sealed in some cold archival freeze, as if they were trying to preserve it for future resurrection. Queer and eerie, like trying to revive the dead by reading their letters aloud in a voice not your own.

As I sat in the sleep room, while time ticked away and the question remained unanswered, my own life began to feel like one of those Cass Mastern stories. A faded, half-remembered romance from some Civil War–era St. Louis or some other flyover state.

Something crumbling. Something trying to speak, but only managing to echo.

6

If each of the three wake-ups was an equally good candidate for what I meant when I said, “This is my first wake-up,” and if today had an equal chance of being Monday or Tuesday, then it should hardly matter if I chose to say, “Today is Monday.” But I couldn’t bring myself to record that as my answer, because “Today is Tuesday” seemed just as plausible.

The voice reminder sounded again. I heard it, but for some reason, it didn’t register.

I thought of an Episcopal church that stood at the corner of Jackson and Coliseum in New Orleans. I had passed by it once, on a Sunday morning, many years ago.

Of all the things I saw during my time in that city, why this church? Why did I remember it so clearly? Even now, as I pictured it, the image felt so fresh it might have been from just yesterday—no, from this Sunday, the one I must’ve lost when they put me to sleep.

I remembered the parishioners lining up outside the pink church. The exterior—stucco, softly sunlit—looked almost unreal, like something from a faded photograph. The people were dressed well, modestly, in that quiet old-money kind of way. Not flashy, just composed.

I didn’t need to be told they were Irish; I knew it somehow. It was in their faces, in the way they stood waiting for the doors to open, in the way their presence held memory without ever speaking it.

7

Then the voice cut in again. A dry, mechanical reminder:

“You have not yet answered the question.”

The prompt pulled me back. Once again, I tried to focus, tried to think—

What are the odds of this being Monday?

So I continued to sit on the edge of the bed, thinking—futilely, for all I knew.

Maybe, when I got tired of all this, I’d just find a coin and flip it—let the chips fall where they may. Or I’d toss both slippers into the air and let the one that landed first be Monday. Either way, the experimenters would still have to pay me, even if that’s how I reached my conclusion.

Then again, maybe they were the most patient people who ever lived, willing to tolerate my endless wavering and indecision. So far, I hadn’t heard a single sound from outside the room—nothing human, at least. Maybe that was intentional. Maybe they were worried that any movement, any stray noise, even a word spoken to hurry me along, might accidentally reveal something I wasn’t supposed to know until after I’d answered the question.

My dilemma reminded me of a game show I’d seen years ago—something called The Monty Hall Problem. There were three closed doors. Behind two of them: goats. Behind the third: a brand-new car. You picked a door—kept your choice to yourself. Then the host swung open one of the other two doors, revealing a goat. At that point, you got one last chance to change your pick: “Stick with your door, or switch?”

I didn’t care about cars or goats or game shows, but I understood the contestant’s predicament—and I sympathized.

If I switched, it seemed like I’d improved my odds—from one-third to one-half. But each door had a one-third chance to begin with. The fact that one was now revealed to hide a goat didn’t seem to change that. If I switched, wasn’t I just trading one-third for another third?

So what was all the fuss about?

I picked up the recorder and brought it close to my mouth. I opened my lips as if to speak—but for a long while, no sound came out.

8

I once heard this story about a medieval guy named Buridan—some old philosopher type—who, as the scholars behind ivy-covered windows used to say, died under “peculiar circumstances.”

The story goes like this: A donkey—hungry and thirsty—is placed exactly midway between a pile of hay and a pail of water. Both are equally appealing. Both are equally distant. The donkey can’t decide—because there’s no logical reason to choose one over the other. So it doesn’t. It just stands there. Stuck. Until it dies. Of hunger and thirst.

I swear I once—on a playground in Somerville—heard some big kids explaining to smaller kids that “jackass” means “donkey butt.” And they were right in more ways than they knew.

Anyway, that was me. Not dead yet, but starting to feel like I was turning into one of those donkey butts—paralyzed between equally dumb options.

9

I saw a single outbuilding—a squat little shed of concrete and metal—standing alone against a featureless backdrop, shrouded in mist. I recognized it right away: the morgue I used to see as a kid, the one where the county hospital parked the dead.

One evening, just as night was falling, some friends and I passed by it. No one could walk past that place without feeling the strange pull it gave off—a quiet force that made it hard not to glance in its direction. That night was no different.

We stood about a hundred yards away, teasing one another, casting sideways glances. It was only a matter of time before someone said something. Sure enough, a dare was born, and a wager quickly followed: five packs of cigarettes to anyone who’d walk into the morgue, close the door behind them, and stay inside for a few hours.

I took the bet.

I started walking casually toward the shed, not fully knowing what I was doing. I entered, looked around, and reached for the rusty door handle. It wouldn’t budge at first. The hinges were corroded, and the threshold was clogged with dirt and debris. It hadn’t been used in a long time. I had to clear the way and force the door shut.

When I finally managed to close it, I turned to survey the interior. There were two cement blocks inside, built like crude beds—one on either side, symmetrical in their bleakness. The tops were bare, but the corners and the floor around them told a different story. Apparently, no one ever swept or cleaned after use. All kinds of detritus littered the place, including clumps of hair—shaved from dead bodies and left there like sweepings at a barber shop.

I looked at the two slabs and picked one to lie down on.

As I settled onto the cement, I felt a coldness seep into my back. I stared up at the rotting ceiling, full of holes. Then I closed my eyes.

So this was where they kept the bodies before the relatives came to fetch them. Hard to imagine what kind of dreams the dead might have. Surely the dead don’t remember anything. But if they could… it would be something to know what their memories might be. Probably not so different from ours—regrets, unfulfilled wishes, failed hopes. Or maybe the dead had no dreams at all.

And really, how different is that from the living? Not everyone carries hatred, dreams of grandeur, or plans for the weekend.

And in that stillness, the dead came. Not as ghosts, not even as visions. Just voices—quiet, ordinary voices. Each told me something that had happened while they were alive. Something left unfinished. Something they never got to explain.

What amazed me was how ordinary their stories were—so much like the stories the living tell. And once that realization hit me, their tales lost all mystery. Not even the cries of sorrow from Hades—or from the Yellow Springs, if you were Chinese—not even the tears they never shed, could move me.

I felt bored. I yawned. And then I dozed off.

That’s how I won the challenge—five packs of cigarettes.

10

And now I was here, sealed in this room, memories returning like a slow tide. I was supposed to be thinking about probabilities. I was supposed to answer a question—about Today, about Tomorrow.

But all I could think of was that slab I’d lain on years ago.

Just as I began to drift again, the voice cut in once more:

“What probability are you inclined to assign to today’s being Monday?”