The Fighting Cricket

A story from Liaozhai Zhiyi (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio)

During the Xuande reign, the palace grew fond of cricket fights and ordered the people to provide fighting crickets every year. These creatures weren’t native to the western parts, yet a magistrate in Huayin, eager to curry favor with his superiors, presented one as tribute. It happened to fight exceptionally well, so from that moment he was required to supply them regularly. The magistrate passed this demand down to the village head.

In the market towns, loafers who fancied themselves heroes would catch fine crickets, keep them in cages, and drive up their price, treating them as luxury goods. The petty clerks were crafty and predatory, and used this new “tax” to squeeze the villagers. Each demanded cricket could ruin several households.

In that district lived a scholar named Cheng, a man who taught village children but had long failed to pass any examinations. He was honest and slow of speech. A rogue clerk, knowing his mild nature, tricked him into serving as village head. Try as he might, Cheng could not escape the position. Within less than a year his small savings were exhausted.

Then came the season for collecting crickets. Cheng didn’t dare extort his villagers, but since he had none to hand over, he also had nothing with which to compensate the officials. He grew so anxious he thought of dying. His wife said, “What good is dying? Better to search for a cricket yourself. Who knows, you might get lucky.” Cheng agreed.

Day after day he went out at dawn and returned at dusk, carrying bamboo tubes and wire cages. He searched among broken walls and tangled grasses, lifting stones and probing into holes, trying every method he had heard of. Nothing worked. At most he caught two or three weak, worthless little things. The magistrate pressed him under a strict deadline, and after more than ten days Cheng was flogged until the flesh between his thighs festered and bled. He could barely even walk, much less catch insects. Lying on his bed, he thought only of ending his life.

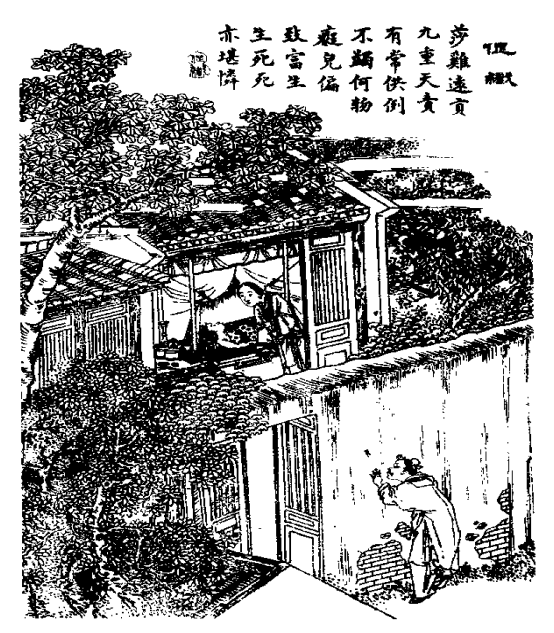

At that time a hunchbacked fortune-teller came to the village, famed for her spirit-medium rites. Cheng’s wife scraped together a little money and went to consult her. At the doorway she saw painted talismans of red maidens and white crones pasted everywhere. Inside was a small inner chamber behind a hanging curtain. In front of it stood a table of incense. The petitioner lit incense, knelt, and bowed. The medium stood beside her, looking into the air and chanting with fluttering lips, as if petitioning unseen spirits. All around stood silently listening. After a moment, a slip of paper was tossed out from behind the curtain. It always contained exactly what was on the questioner’s mind, never off by even a hair.

Cheng’s wife placed her payment on the altar and bowed while the incense burned. After some time the curtain stirred and a slip fell to the floor. She picked it up. There were no words—only a drawing: a palace-like hall, resembling a Buddhist monastery; behind it, a low hill with strange rocks lying in confusion, bristling thorny bushes, a green, bald-headed frog crouching there; beside it, a toad poised as if about to leap and dance. She studied it but could not fathom its meaning. Still, seeing a cricket hidden in the drawing stirred a little hope in her. She took the paper home and showed it to Cheng.

He pondered it again and again. “Could it be showing me where to hunt?” he thought. He studied the scenery in the drawing more carefully. It looked uncannily like the large Buddha pavilion east of the village. Limping and leaning on his staff, he took the drawing and went behind the temple. There rose an old mound like the one in the picture. Following its slope, he found a cluster of crouching rocks, looking exactly like the painting. He crept through the weeds, listening carefully as he walked, searching as if for a needle in hay. His mind, eyes, and ears were all exhausted, and he found nothing.

Still he kept searching. Suddenly a mangy, bald-headed toad jumped out. Cheng’s heart leapt. He hurried after it. The toad slipped into the grass. Following its trail, he found an insect crouched among thorn roots. He pounced, but it darted into a stone crevice. He poked with a sharp blade of grass; it wouldn’t come out. Only when he poured water from his bamboo tube did it finally emerge. It was magnificent: large body, long tail, blue neck, golden wings. Overjoyed, Cheng brought it home. The family celebrated as though they had acquired a priceless jade.

He placed it in a basin of earth and tended it like a treasure. Its shell turned crab-white and chestnut-yellow, glowing with health. He guarded it with utmost care, saving it for the deadline to satisfy the officials.

Cheng had a nine-year-old son. One day, seeing his father away, the boy sneaked to the basin. The cricket leapt out and dashed away. The child chased it desperately, and when he finally grabbed it, its leg had snapped, its belly torn, and moments later it died. Terrified, the boy cried and told his mother.

The mother’s face went chalk-white. She cursed him: “You little bringer of ruin! This is our death! When your father returns, you can die together!” The boy ran out in tears. When Cheng came home and heard what happened, it felt like being plunged into ice. He demanded the boy, but the child was nowhere to be found. Soon they discovered his body at the bottom of the well.

Cheng’s fury collapsed into grief; he wailed until he fainted. Husband and wife sat in their straw hut, no smoke rising from the stove, staring at each other in despair.

At dusk they prepared the child’s body for burial. As they lifted him, they felt faint breath. They laid him on the bed, and by midnight he revived. Husband and wife were relieved, but the boy’s spirit seemed dull and sleepy. Cheng glanced at the empty cricket cage and felt his heart wither. Even the joy of his son’s revival could not ease him. He sat awake all night.

At dawn, lying in misery, he suddenly heard cricket chirping outside. He jumped up and looked: there it was, alive. Delighted, he tried to catch it. Each time he reached, it leapt away. He covered it with his palm—nothing. When he lifted his hand, it bounded off again. He chased it around a corner and lost sight of it. Looking around in confusion, he saw a tiny cricket clinging to a wall. It was short, blackish-red—not the same insect. Cheng dismissed it as too small.

But as he stood there, searching, the tiny cricket suddenly leapt into his sleeve. He looked: it resembled a little earwig, with plum-blossom-patterned wings, square head, and long legs. It seemed promising. Overjoyed, he took it home. Before offering it to the magistrate he wanted to test its fighting ability.

In the village lived a youth who kept a cricket he nicknamed “Blue Crab-Shell,” undefeated in every match. He bragged endlessly and set a high price for it, though no one bought it. Hearing Cheng had a cricket, he came to visit. Seeing Cheng’s insect, he burst out laughing, then put his own in Cheng’s cage for comparison. Cheng saw how huge and powerful the youth’s cricket was and felt ashamed, unwilling to compete. But the youth insisted. Cheng thought, “If mine is worthless anyway, I might as well gamble and give them a fight.” So he placed them in the fighting bowl.

Cheng’s little cricket crouched motionless like a wooden rooster. The youth laughed louder. He teased the cricket’s whiskers with a bristle; still it did not move. More laughter. After several pokes, the little cricket suddenly flew into a rage and charged. The two grappled fiercely. Then Cheng’s insect sprang up, raised its tail and stretched its feelers, and bit straight into the rival’s neck. The youth was shocked and quickly separated them. The little cricket chirped proudly, as though reporting victory to its master. Cheng was ecstatic.

As they admired it, a chicken darted in and pecked. Cheng shouted in horror. Luckily the peck missed, and the cricket leapt a foot away. The chicken lunged again. The cricket was nearly under its claws. Cheng froze in panic. The chicken stretched its neck to strike when suddenly it jerked backward, flapping wildly. Looking closely, they saw the cricket latched onto the chicken’s comb, clinging with all its might. Cheng’s amazement turned to joy, and he quickly scooped it into the cage.

The next day he presented it to the magistrate. The magistrate, seeing its small size, scolded him. Cheng explained its feats. The magistrate didn’t believe him. They tested it against other crickets; it beat them all. They tested it with chickens; it performed as Cheng had said. Only then was Cheng rewarded.

The magistrate presented it to the provincial governor. The governor, delighted, offered it in a golden cage to the Emperor, with a note describing its talents. In the palace, it was tested against butterflies, mantises, beetles, green-striped crickets—all manner of creatures. None surpassed it. Whenever zither or lute music played, it danced to the rhythm, astonishing everyone.

The Emperor was greatly pleased and gifted the governor a fine horse and silks. The governor, remembering where it came from, soon reported Cheng’s service as “exceptional.” The magistrate, pleased, freed Cheng from his duties and instructed the education officer to enroll him in the county academy.

A year later, Cheng’s son recovered his former vitality. He said, “I turned into the cricket for a time. I was light, quick, and good at fighting. Only now have I returned.” The governor gave Cheng generous gifts. Within a few years Cheng owned a hundred acres of land, pavilions with ten thousand beams, and herds of cattle and sheep by the thousands. When he traveled out, his fur coat and horse outranked those of old noble families.

The Historian of the Strange comments:

“When an emperor casually takes a liking to something, he may soon forget it—but those who carry out his whims treat it as law. Add to that corrupt officials, and the people must sell wives and children without end. Thus every step an emperor takes touches upon the lives of the people and cannot be taken lightly. That Cheng, once impoverished because of a cricket, should later become wealthy because of one—who could have imagined it when he was being beaten on the village head’s behalf? Heaven wished to reward a man of generous heart, so even governor and magistrate alike received blessings from a single cricket. Truly, when one person ascends, even his chickens and dogs become immortals.”

聊斋志异•促織

宣德間,宮中尚促織之戲,歲征民間。此物故非西產。有華陰令,欲媚上官,以一頭進,試使斗而才,因責常供。令以責之里正。

市中游俠兒,得佳者籠養之,昂其直,居為奇貨。里胥猾黠,假此科斂丁口,每責一頭,輒傾數家之產。

邑有成名者,操童子業,久不售。為人迂訥,遂為猾胥報充里正役,百計營謀不能脫。不終歲,薄產累盡。會征促織,成不敢斂戶口,而又無所賠償,憂悶欲死。妻曰:「死何益?不如自行搜覓,冀有萬一之得。」成然之。早出暮歸,提竹筒銅絲籠,于敗堵叢草處探石發穴,靡計不施,迄無濟。即捕三兩頭,又劣弱,不中于款。宰嚴限追比,旬余,杖至百,兩股間膿血流離,并蟲不能行捉矣。轉側床頭,惟思自盡。時村中來一駝背巫,能以神卜。成妻具資詣問,見紅女白婆,填塞門戶。入其室,則密室垂簾,簾外設香幾。問者爇香于鼎,再拜。巫從旁望空代祝,唇吻翕辟,不知何詞,各各竦立以聽。少間,簾內擲一紙出,即道人意中事,無毫髮爽。成妻納錢案上,焚香以拜。食頃,簾動,片紙拋落。拾視之,非字而畫,中繪殿閣類蘭若,后小山下怪石亂臥,針針叢棘,青麻頭伏焉;旁一蟆,若將跳舞。展玩不可曉。然睹促織,隱中胸懷,折藏之,歸以示成。成反復自念:「得無教我獵蟲所耶?」細矚景狀,與村東大佛閣真逼似。乃強起扶杖,執圖詣寺后,有古陵蔚起。循陵而走,見蹲石鱗鱗,儼然類畫。遂于蒿萊中側聽徐行,似尋針芥,而心、目、耳力俱窮,絕無蹤響。冥搜未已,一癩頭蟆猝然躍去。成益愕,急逐之。蟆入草間,躡跡披求,見有蟲伏棘根,遽撲之,入石穴中。掭以尖草不出,以筒水灌之始出。狀極俊健,逐而得之。審視:巨身修尾,青項金翅。大喜,籠歸,舉家慶賀,雖連城拱璧不啻也。土于盆而養之,蟹白栗黃,備極護愛。留待限期,以塞官責。

成有子九歲,窺父不在,竊發盆,蟲躍躑徑出,迅不可捉。及撲入手,已股落腹裂,斯須就斃。兒懼,啼告母。母聞之,面色灰死,大罵曰:「業根,死期至矣!翁歸,自與汝復算耳!」兒涕而出。未幾成入,聞妻言如被冰雪。怒索兒,兒渺然不知所往;既而,得其尸于井。因而化怒為悲,搶呼欲絕。夫妻向隅,茅舍無煙,相對默然,不復聊賴。

日將暮,取兒藁葬,近撫之,氣息惙然。喜置榻上,半夜復蘇,夫妻心稍慰。但兒神氣癡木,奄奄思睡,成顧蟋蟀籠虛,則氣斷聲吞,亦不復以兒為念,自昏達曙,目不交睫。東曦既駕,僵臥長愁。忽聞門外蟲鳴,驚起覘視,蟲宛然尚在,喜而捕之。一鳴輒躍去,行且速。覆之以掌,虛若無物;手裁舉,則又超而躍。急趁之,折過墻隅,迷其所往。徘徊四顧,見蟲伏壁上。審諦之,短小,黑赤色,頓非前物。成以其小,劣之;惟彷徨瞻顧,尋所逐者。壁上小蟲。忽躍落襟袖間,視之,形若土狗,梅花翅,方首長脛,意似良。喜而收之。將獻公堂,惴惴恐不當意,思試之斗以覘之。

村中少年好事者,馴養一蟲,自名「蟹殼青」,日與子弟角,無不勝。欲居之以為利,而高其直,亦無售者。徑造廬訪成。視成所蓄,掩口胡盧而笑。因出己蟲,納比籠中。成視之,龐然修偉,自增慚怍,不敢與較。少年固強之。顧念:蓄劣物終無所用,不如拚博一笑。因合納斗盆。小蟲伏不動,蠢若木雞。少年又大笑。試以豬鬣毛撩撥蟲須,仍不動。少年又笑。屢撩之,蟲暴怒,直奔,遂相騰擊,振奮作聲。俄見小蟲躍起,張尾伸須,直龁敵領。少年大駭,解令休止。蟲翹然矜鳴,似報主知。成大喜。

方共瞻玩,一雞瞥來,徑進一啄。成駭立愕呼。幸啄不中,蟲躍去尺有咫。雞健進,逐逼之,蟲已在爪下矣。成倉猝莫知所救,頓足失色。旋見雞伸頸擺撲;臨視,則蟲集冠上,力叮不釋。成益驚喜,掇置籠中。

翼日進宰。宰見其小,怒訶成。成述其異,宰不信。試與他蟲斗,蟲盡靡;又試之雞,果如成言。乃賞成,獻諸撫軍。撫軍大悅,以金籠進上,細疏其能。既入宮中,舉天下所貢蝴蝶、螳螂、油利撻、青絲額……一切異狀,遍試之,無出其右者。每聞琴瑟之聲,則應節而舞,益奇之。上大嘉悅,詔賜撫臣名馬衣緞。撫軍不忘所自,無何,宰以「卓異」聞。宰悅,免成役;又囑學使,俾入邑庠。后歲餘,成子精神復舊,自言:「身化促織,輕捷善斗,今始蘇耳。」撫軍亦厚賚成。不數歲,田百頃,樓閣萬椽,牛羊蹄躈各千計。一出門,裘馬過世家焉。

異史氏曰:「天子偶用一物,未必不過此已忘;而奉行者即為定例。加之官貪吏虐,民日貼婦賣兒,更無休止。故天子一跬步皆關民命,不可忽也。第成氏子以蠹貧,以促織富,裘馬揚揚。當其為里正、受撲責時,豈意其至此哉!天將以酬長厚者,遂使撫臣、令尹、并受促織恩蔭。聞之:一人飛升,仙及雞犬。信夫!」