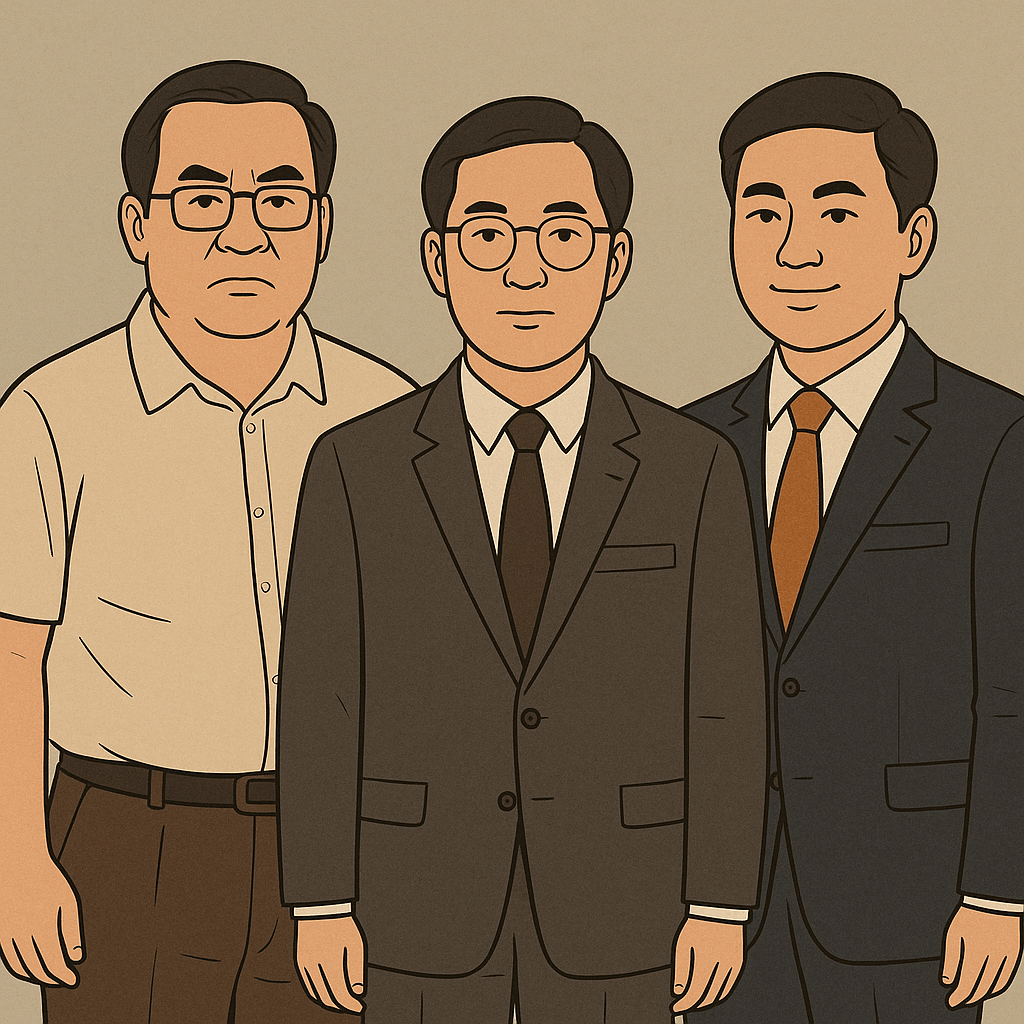

Three Types of China Haters Who Are Ethnically Chinese

Over the past decade, I’ve encountered a strange breed of Chinese people—not dissidents, not reformists, not critics motivated by genuine concern, but China haters who are ethnically Chinese—people who are visibly Chinese, whose wealth, education, and career were made possible by China, yet who resent and despise the very system that nurtured them. Some call them “bananas”—yellow outside, white inside—but that doesn’t quite capture the essence. A banana may admire the West. These people hate China—not out of principle, but out of personal, thwarted self-interest.

Formally, we could call them “pro-USA” Chinese, but that’s too gentle and too flattering. Let’s call this for what it is: a particular kind of betrayal, born not from conscience but from greed, entitlement, and resentment.

Based on my encounters and reflections over the years, I’ve classified these individuals into three types. If you ever meet a mainland Chinese who’s moved to the U.S. or Canada, who claims to “love freedom” but doesn’t speak a word of English, they might just belong to one of the following categories:

1. The First Type: The Offshore-Obsessed Tycoon

These are businesspeople who made their fortunes by exploiting China’s transition into a market economy. They waded into the muddy waters of “low-tech, high-profit” industries—strip mining in Shanxi, mass housing development during the property boom—and got rich. Not because they were Steve Jobs-level visionaries, but because they were early enough to pluck the low-hanging fruit of an imperfect market.

But now? The game has changed. Beijing tightened regulations. Anti-corruption campaigns have teeth. Capital flight is harder. Suddenly, their billions, earned within the Chinese system, are trapped inside a system they now resent.

If these moguls ever confided in you—truly confided—they would say something like:

“I hate China because it won’t let me move my money overseas.”

Think of Xu Jiayin (许家印) or the countless unnamed bosses who used China’s system to get rich, and now blame that same system for not helping them move their money to the U.S.—the country they have neither contributed to nor cared about, except as a vault.

2. The Second Type: The Dislocated Scholar

This type is an academic in the humanities—usually with a degree from a Chinese university, maybe a stint as a visiting scholar at an American college. They speak broken English. They attend conferences on Confucianism (oh, the irony!) in Chicago, feel academically “global,” and privately believe that China is the problem.

In their mental geography, there is “the world”—meaning the U.S. and Europe—and “China,” an embarrassing exception. They don’t say it aloud, but it shows in every sigh, every comparison, every “In the West, they do it like this…”

Ask them why they dislike China, and you’ll hear something like:

“Because China isn’t part of the world.”

Self-alienation is their second nature. They admire thinkers like Edward Said, but never apply the critique to themselves. From afar, they not only desire to assimilate—the deeper shame is that they want to disown.

3. The Third Type: The Frustrated Official

At first glance, this one may surprise you. A government official who hates China? Yes. But dig deeper.

China is one of the last countries on earth that actively prevents wealth from buying political power. Want to hold office? You must rise through the ranks. Want to get rich? Go into business. The separation of money and power is built into the system.

That means a top official signing off on billion-yuan contracts cannot personally profit. In their fantasies, they picture Swiss bank accounts. Cayman Islands. Offshore funds. Just like their American counterparts—only it’s all illegal in China.

Ask such an official why they hate China, and the confession would go like this:

“Because contractors can’t wire money to my offshore account.”

They crave not freedom, but the freedom to be corrupt with legal impunity. To them, the U.S. is not a model of democracy; it’s a loophole, a paradise for legalized bribery and campaign money.

A Hatred Born of Frustration, Not Principle

These are not rebels, visionaries, or philosophers. They are not “dissidents.” They are what we might call the disappointed beneficiaries of the Chinese system. And their hatred of China stems from a deep personal grievance: China does not let them do whatever they want with their wealth, status, or imagined identity.

They are Chinese in face, blood, and history—but they long to be American in convenience and self-interest. They do not fight for freedom—they flee when they cannot cash out.

And that—of all things—is what makes their hatred so distinct, so revealing—and so sad.