たますず (jade bells) by Yasunari Kawabata

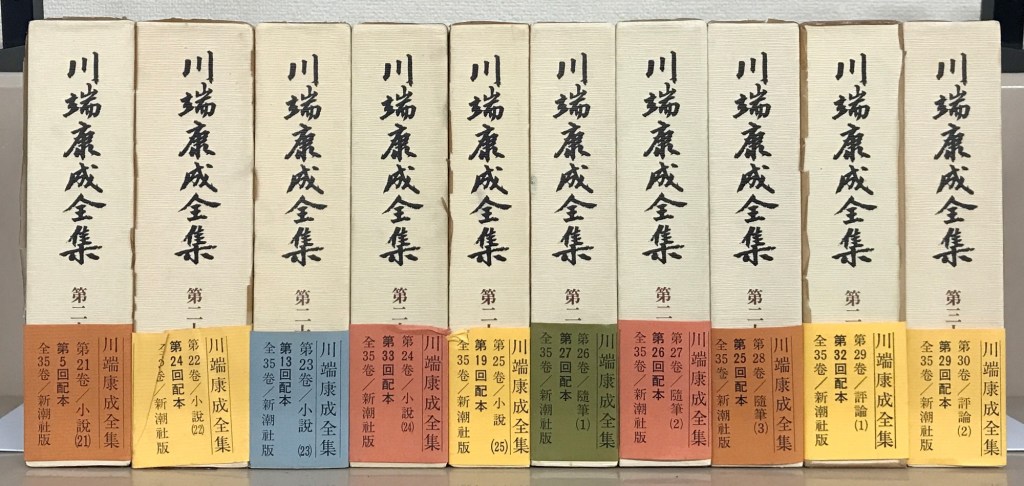

Translator’s note: The Japanese title of Kawabata’s story is たますず (tamasuzu), composed of たま (“jade”) and すず (“bell”). The story appears in 《川端康成全集》(新潮社). One further note: my younger sister, who passed away about ten years ago, was named 玉玲 (“sound of jade”). For reasons I cannot fully explain, I thought of her today; that memory led me to this story by Kawabata, and in turn, to this translation.

They say that even when Haruko was at her last breath, she was still listening to her jade bells.

Thread two or three crescent-shaped pieces of jade on a cord; give them a gentle shake; the stones strike one another and make a faint sound. Haruko called such an instrument “jade bells.”

Haruko had three crescent jades. Was it better to ring them with three stones, or with two? In the end she decided that the sound made by three was far more pleasing than the sound made by many.

As one of Haruko’s keepsakes, I received one crescent jade.

Someone said, “Why not tie it to your pocket-watch chain…?”

It is a little large. But…

As an ornament on a watch chain it is indeed rather big. Still, my pocket watch—very old—was not small either. So, as people suggested, I tied Haruko’s crescent jade onto my watch chain.

My pocket watch, though old, is not ancient—at most fifty years or so. Haruko’s crescent jade, however, is an antique: a relic from Japan’s remote past. It may even be a stone from the age of the gods. Perhaps it is not far removed from the Yasakani no Magatama, the curved jewel among the Three Sacred Treasures.

If, as records say, the Yasakani no Magatama was made by threading many jewels on an eight-shaku cord—how many stones must it have held! And what a dazzling profusion of beauty those jewels must have been! I imagine that in ancient Japan it must have been extraordinarily difficult to gather together a set of gems worthy of any of the Three Sacred Treasures. The crescent jade I received from Haruko was said to be a precious ancient stone. Even among the many jewels of the Sacred Treasures, it would not have looked inferior.

Unfortunately, I know nothing about ancient jade. I cannot even tell what Haruko’s crescent jade truly is—jadeite, or rōken? I cannot tell. Rōken may be a kind of jadeite, and even Haruko’s parents were unclear about it.

“Is it jadeite?” I asked.

“Yes,” they answered.

If I asked again, “Is it rōken? Is rōken a kind of jadeite?”

“Yes,” they would answer the same way.

The crescent jade had been left behind by Haruko’s grandfather.

As for the antique-sounding term “jade bells,” I only know that it suggests a ringing tone—clear, intermittent, present and absent, as if there and not there. Yet I cannot trace the word’s origin. Does it come from the striking sound itself? Or from the instant of the jade’s motion? But that does not matter. Let it be as Haruko wished: let us take the ting-ling sound of jade striking jade as the source of the word.

If one consulted archaeologists and philologists and they declared this explanation wrong, it would be terribly disappointing—an utter dampening of the spirit.

And though “jade bells” may be an old expression, was it born in the very age when crescent jades first appeared, or much later? Is it a word found in the Man’yōshū? Or did it arise only after the Shinkokinshū? If one insists on digging to the root, one may only end in disillusion.

So I will simply call Haruko’s delicate ringing jade bells.

I heard Haruko’s jade bells only once—on the day I accepted her keepsake. The three crescent jades were given separately: to me, to Seta, and to Haruko’s younger sister, Reiko. Once the stones were divided one by one, the jade bells could be heard no more.

That day Haruko’s mother lifted the cord with the jades tied to it, held it close beside her ear, and shook it gently.

“Like birdsong, isn’t it?” I said, listening intently.

“Mr. Seta—did Haruko ever let you hear it?”

“Ah—n-no…” Seta stammered, his face flushing at once.

Jade bells—truly like the song of a small bird.

The sound was like what one might call an after-echo: the waves of sound were weak, low, lingering; it felt as though one were inside a quiet dream. What bird did it resemble? I could not recall. And yet I felt I had heard it before. Only in a place utterly calm and hushed would such a bird sing a melody so lovely. Needless to say, such a melody could be heard only in Japan: soft and turning, endlessly varying, archaic and elegant—marvelously exquisite. It was not one bird, nor one single voice.

I was carried away.

Haruko’s mother stopped shaking the jade bells and laid the deep green crescent jade on a piece of white silk. The silk—imitation, perhaps—was padded with cotton; the stitching was fine. It was spread inside a small paulownia-wood box. The crescent jade, wrapped in purple crêpe gauze, lay upon the white silk.

When Haruko’s mother had taken the jade a moment earlier, she had drawn it out together with the white silk. Now I saw, inside the box, a folded sheet of paper with ink marks on it.

“Is that a record of the jade’s provenance?” I asked.

“No.”

I unfolded the paper Haruko’s mother had removed. Two poems were written on it.

Last night, in the sound of the jade bells, I saw your lovely shadow—

At dawn, why does my heart so ache?

The jade bells bring the morning’s dew, the sorrowful tears—

Yet they cannot keep, within this small room, the autumn wind that mourns a lover.

Ah. I savored them, drunk with wonder, yet in my ignorance I did not know who had written them.

“This is Miss Haruko’s handwriting?”

“Yes.”

“After her illness worsened…?”

“Yes. I think she wrote them after she knew she did not have long. Before, it seems there was no such thing.”

I glanced at Haruko’s photograph hanging in the alcove. It was large, with a black ribbon tied to it. In front of the photo stood a large white porcelain vase from the Yi Dynasty, filled with pink roses—though there were only a few blooms.

Though it was only a photograph, Haruko’s eyes were still strikingly beautiful. Her face was wan; her jaw looked thin.

That is, beneath the lips there was a rounded fullness, slightly pointed, projecting a little forward. The whole outline was sharply defined, vivid and lifelike. And her expression seemed absorbed in deep thought. The moment I became conscious that this was only the photograph of the dead, her gaze seemed to advance toward me coldly.

My eyes shifted to Haruko’s younger sister, Reiko.

Reiko was seventeen, still in secondary school, and she resembled her sister. She probably did not yet understand love. No fruit of weathered feeling could be seen on her face. To ripen as her sister had, perhaps she would need a long season of hardening. Her face and Haruko’s were indeed very similar—yet I did not know whether her spirit was also the same. Reiko was full-bodied, but she looked as though she might be simple-minded.

My eyes returned to Haruko’s photograph. If not for the black ribbon, it would have been the portrait of a living woman—of course, it was taken while she lived. Yet seated before the vividly lifelike photograph of the dead Haruko was her sister, so like her in appearance, and in me there arose a strange, inexpressible fancy.

By the time Haruko was close to her last breath, perhaps her eyes could see nothing. But her ears, surely, could still hear. So I would always lift the crescent jade to her ear and shake it. Haruko’s mother said this, and shook the jade again.

“It seemed she heard it,” she said. “Her brow moved slightly.”

At that moment Reiko, who was listening, also knit her brow faintly.

“Won’t you listen?” Haruko’s mother offered me the jade.

I pinched the cord and shook it once. I did not hear the heart-stirring birdsong. The sound was harsh and disorderly, like rapid panting.

“You’re shaking too hard. Lighter—one shake at a time…”

“Like this?”

“Yes.” Haruko’s mother nodded. “Haruko made it sound much better, but…”

I passed it to Seta. Like me, he could not make the beautiful birdsong appear.

Seta passed it to Reiko. Reiko did better than either of us.

“My sister used to hang it from her neck and shake it,” Reiko said to her mother, and tied the cord around her neck.

Then she shook her head.

“It doesn’t ring.”

Yet I heard it.

She rolled one shoulder; again I heard the jade bells.

Reiko seemed to have just come home from school. The crescent jade hanging at the neck of her sailor-style uniform looked oddly mismatched. Such an ancient, heavy necklace would not suit any modern person. Perhaps Reiko had tied the cord too short: the top of the jade pressed against her throat, the bottom rested on the front collar of the sailor blouse. It was not pretty—but Reiko’s neck, thick with dark hairs, shone with a vivid beauty because of the jade.

I began to imagine the ancient person who first discovered crescent jade. In those days, surely people listened to the ringing as their bodies moved. Yet I knew nothing of the customs of that era. I vaguely recalled historical illustrations from school and found it strange: ornaments made by threading several crescent jades did not seem to have the stones pressed tightly together—there were spaces between. If so, the stones would not strike each other as the body moved. Then why did the jade bells not ring? Or was it that, in love, one was not allowed to let the jade bells sound? I pictured ancient lovers moving carefully so as not to make the bells ring.

The three crescent jades hanging at Reiko’s throat—perhaps because she shook her head and shoulders with a sincere, docile gentleness—began to sound, and I heard the jade bells.

So the crescent jade made me imagine ancient people—and made me think even more of Haruko, its owner. Like Reiko now, Haruko too must once have worn the three crescent jades at her neck, moving her body with mild grace to keep the lovely sound of the jade bells flowing without end. Reiko was imitating her sister.

And I wondered: when Haruko spoke of love, did she also wear the crescent jade at her throat? Did she ever let her lover hear the jade bells? Haruko’s fascination with the jade bells—her intoxication with them—seemed to me itself a sign of a woman’s wisdom in matters of love.

If the jade bells I had just heard were sounding from the neck of a woman in an embrace, they would surpass the loveliest whispered confessions.

When Haruko’s mother first made me listen, I had not imagined how wonderful it would be to hear the sound while pouring out one’s heart. But now, as Reiko made it ring with her neck, I suddenly understood—and even I was surprised at myself.

And I remembered Haruko’s mother’s question to Seta:

“Did Haruko ever let you hear the jade bells?”

Seta had faltered, and his face had reddened at once. If he truly had heard them, it must have been at a moment of love. I felt jealous of Seta. And within that jealousy there was also an irredeemable regret: Haruko was dead, and so to hold her close and listen to the jade bells was now impossible.

Just like the poem Haruko had placed in the wooden box—

Last night, in the sound of the jade bells, I saw your lovely shadow—

At dawn, why does my heart so ache?

And now it became—

The jade bells bring the morning’s dew, the sorrowful tears—

Yet they cannot keep, within this small room, the autumn wind that mourns a lover.

To have never heard the jade bells sounding from Haruko’s neck felt as though I had lost the happiness of a lifetime. To think of loving her only after she had left the world—yes, it was a petty, worldly ugliness. Yet a woman who can let you hear jade bells while speaking of love—there may never be a second.

But did Haruko, while confessing love, truly ever let the other person hear the jade bells? Only Seta could know.

I was about to study Seta—to see what his face would look like as Reiko’s neck lightly shook, and the jade bells sounded long and soft—when Reiko untied the cord and placed the crescent jade back on the white silk.

Haruko’s mother drew the cord out, then gave each of us one stone. Before coming that day, Seta and I had already discussed dividing Haruko’s keepsake.

Seta looked at his jade in his palm and said:

“Give me something to wrap it in.”

“Yes.”

Haruko’s mother handed him a piece of purple cloth.

“Mr. Shinmura, don’t you want something to wrap yours?” she asked. “Jade is hard; you could carry it loose in your pocket, but…”

Seta wrapped his jade and put it in his pocket. Young Seta seemed less interested than I was. The exquisite jade bells did not seem to move him either. If so, perhaps Seta had never heard the jade bells while Haruko spoke of love.

Reiko laid the jade on the white silk and put it back into the box.

“We divided them according to age,” Haruko’s mother said. “Mr. Shinmura received the best piece; next is Seta’s; then Reiko’s…”

That order, however, ran exactly opposite to the depth of Haruko’s ties to each of us.

“I don’t understand these things,” Haruko’s mother added. “But the piece given to Mr. Shinmura is said to be the finest. Crescent jades in ancient times were like jadeite today, perhaps.”

“Now that they’re taken apart like this, we’ll never hear the jade bells again, will we?” I said.

“Haruko is gone, and there’s no one here to listen… But on the day of her memorial, if you can come, bring your pieces. Then we’ll hear the jade bells again.”

I thought that was a good idea, and said to Seta:

“Next month, on the memorial day, bring your jade.”

If the separated crescent jades were to reunite on the memorial day, perhaps Haruko’s spirit too would return home to listen.

I cut the cord and tied my crescent jade onto my silver watch chain.

I drove past the gate at Akasaka. There is a bridge there leading to Shimizudani Park. In the green thickets across the bridge, double-flowering cherry blossoms were in bloom. At the center of the bridge, carp streamers hung from the railing. It was late April, and the Boys’ Festival was near. The boundary between late spring and early summer—when the wind is gentle and pleasant. In the tender new greenery, the tender double blossoms stood out. I raised the crescent jade to shade the light and pressed it close to one eye, closing the other, pretending to look through the jade at the grove across the ditch.

“Ah—how beautiful!” I exclaimed.

Of course, through a stone as thick as a finger one could not see the opposite bank. Yet I saw the crescent jade itself—clear and shining.

Was it azure, or emerald? It was a deep green far greener than any green in imagination—an extraordinary color the world had never known. The stone seemed to drink in beauty and hide it within, and yet it was brilliantly translucent, building inside itself a profound and dazzling world. Was it the sky of fantasy, or the sea of dreams?… And yet outside, reality was the radiant May of this world.

Is the finest jadeite today this color? I do not know—there is none in my house. If ancient Japan did not produce jadeite, then imagine how carefully people of that age must have polished such stones into such gems.

My car went from the Akasaka gate toward the Yotsuya gate. The inner beauty of the crescent jade astonished me, and the green shade of the roadside trees seemed all the more vivid. Across the ditch to the right were small trees; to the left was the former Akasaka Palace, where the ordered greens of the grove wavered in the water. I could not tell whether the roadside trees were ginkgo or plane trees. Looking out the window at the newly opened leaves, I still could not decide. Because the new leaves were small, the trunks looked dark. Those dark trunks seemed to be caressing the tender leaves, and my eyes brightened.

And then, suddenly, the dark trunks made my heart sink. For I recalled something Haruko’s mother had said: Haruko dreamed of black bamboo, and knew she was near the end.

Dreams are hard to explain, and I heard it only secondhand. Still, she meant black bamboo—its shadows drifting—this, surely, was not mistaken.

A fierce wind rose; mist swirled thickly. A bamboo grove was shaken by the wind, entangled by cold fog. The fog carried a hint of purple, rare in the world. The bamboo culms were black, thick black canes interlaced like teeth, rising tall. The leaves were green, like real bamboo leaves—yet strangely, only the stalks were black. When Haruko woke, the black bamboo culms remained lodged in her heart.

There is indeed such a thing as black bamboo, and there are bamboos in ink paintings. But the black bamboo of a dream does not easily call those to mind. Haruko found it ominous—an unhappy sign.

For two or three days after that dream she kept it from me. After she told me, she said: “I am going to die.” That is what Haruko’s mother said.

According to her, Haruko only said she had dreamed of black bamboo stalks, without telling what came before or after. What did Haruko do in the dream? Was she alone?

At noon, with May approaching, walking along the main road, I still pictured those black bamboo stalks in purple mist and violent wind, and I truly felt chilled. The trunks of the ginkgo—or plane trees—on either side were stout, dark with a brown cast; but the bamboo in Haruko’s dream was wet and gloomy and pitch-black.

I took out the crescent jade again. This time I did not press it tight to my eye as I had at Akasaka; I held it slightly away and let sunlight pass through it. And I felt that within that uniquely deep emerald color there lay an equally rare, heavy sorrow. In ancient times such crescent jades were treasures buried in the tombs of princes and nobles. The bodies disappeared; even the bones vanished; yet the jade remained unchanged, still beautiful. After long ages it was dug up; one piece found its way into Haruko’s hand—and then there came that delicate birdsong. I tasted again the jade bells I had heard before her portrait.

Four or five days later, Seta came to visit.

“Ever since that day I keep having nightmares,” he said. “It’s frightening. Could it be because of the crescent jade? Mr. Shinmura—haven’t you had anything like that?”

“No.” I thought a moment. “Not really.”

“Then perhaps it’s just my nerves.”

“What kind of nightmares…?”

“The worst are the ones about brain blood vessels. When I wake, even the faces are blurred—I don’t know who they were. I only remember five or six men fighting wildly, and I was among them. Was I beaten savagely? Torn apart? Suddenly I lost my senses. My scalp went slack—soft, folded, huge folds you could grab. When I grabbed, there was a large vein inside the fold. Someone pinched that vein between two fingers and kneaded it crudely. Others were shouting: ‘Don’t touch the vessel! Just don’t touch the vessel!’ And I thought, ‘This is it—I’m done for.’ Yet though they were kneading a vein inside my loose scalp, I felt no pain, no suffering—only an unnameable tightness in my chest.”

“What a vile dream.” I frowned. “Surely the crescent jade wouldn’t make you dream such a thing.”

Seta’s nightmare made one shudder even more than Haruko’s dream of black bamboo.

Seta took out his crescent jade and placed it on my desk, still wrapped in the piece of purple cloth. I picked it up, unfastened my own crescent jade from my watch chain, and threaded the two stones onto a cord.

“We agreed that on Miss Haruko’s memorial day we’d reunite the three stones and listen to the jade bells…” I said, lifting the two stones and shaking them.

Even with only two, they chirped faintly like a small bird.

“Is it different from the jade bells with three?” I stared at Seta as I asked.

Seta wasn’t truly listening; his mind seemed elsewhere. Perhaps he was secretly mocking me for playing with jade bells like a child. I felt that the sound I had heard at Haruko’s house—three stones—was not the same as this sound of two stones. If Seta was uninterested, it was natural enough. And so this frail ringing—was it not, then, a solitary sound in the human world, an unmatchable tone?

I untied the stones and handed Seta his piece back. He did not reach out to take it. So I set the two stones side by side. As Haruko’s mother had said, they were divided by age; my stone and Seta’s could be distinguished at a glance. Seta’s looked paler and had a few white patches. Was it originally so, or had it faded from long burial in earth? The quality seemed quite different. I held Seta’s stone to the light; the color inside was not as deep as mine.

“If you like listening to the jade bells,” Seta said, glancing sideways at the jade, “you can keep mine here. I want to test something—whether, without the jade, I stop dreaming.”

“I didn’t have as deep a tie to Miss Haruko as you did,” I said. “So even if I slept with both stones by my pillow, I probably wouldn’t dream. But wouldn’t you be abandoning her?”

Seta’s thick eyebrows drew together. Beneath his freshly shaved sideburns was bluish stubble. His fingers were hairy with dark hair; his eyes were as black as his brows. His long face was sallow, the look of a rough man of the city.

Even sick dreams did not seem to trouble him. He smiled—white teeth, quick intelligence, a kind of charm—then abruptly withdrew the smile, as if his bravado had faltered.

“You mean because Haruko is dead, I’m abandoning her, right?” he said coldly, ignoring me. “If she were alive, you could just as well say she was the one abandoning me.”

I answered in the same tone.

“To say you’re abandoning her is only sparring. We cannot speak of betrayal with the dead. Haruko loved you to her last breath—how could you betray her? I don’t know the whole story of your romance, but I sympathize with her. Through Haruko’s love, I tried to imagine what sort of man you were—and even now, sitting face to face with you, I still do.”

I remembered pressing the crescent jade to my eye at Akasaka. I had meant to look through it at the fresh green across the ditch—yet instead I saw the deep green hidden inside the stone.

“Perhaps you didn’t love her very much,” I said, “and perhaps you didn’t understand her. But her love felt locked—so deep…”

Seta and I were not intimate friends. And Haruko was gone. I did not wish to probe what their love produced. I wanted, instead, to admire Haruko’s love—no, to admire Haruko herself—as one admires a crescent jade, separate from Seta. One could say Haruko loved because she died, and died because she loved; yet the one she truly loved was not the real Seta but someone she imagined. Perhaps I said this out of jealousy.

Seta told me he intended to return his crescent jade to Haruko’s mother. I suspected he had not come to me only because of nightmares; perhaps he carried another pain he could not speak aloud. But since he arrived I had lost all interest in hearing him confess anything. He said the jade was too valuable to keep. Somewhere he had heard that the best crescent jade was worth three to four hundred thousand yen; that startled me as well. Perhaps Haruko’s mother did not know the market value and so divided them among us. Judging from modern jade prices, such stones were indeed expensive. In ancient Japan, the value of jadeite crescent jades is beyond what we can imagine.

“But if you return it,” I asked, “what will you do on Miss Haruko’s memorial day?”

Haruko’s memorial day in May came half a month after we divided the stones. A fine, misting rain fell.

Haruko’s photograph still hung in its place. The white porcelain vase still held pink roses. The four of us sat in the same positions as before. Only Reiko wore not a sailor uniform but a plain, sober dress.

Under the plum tree in the garden, the leaves of mountain white bamboo were soaked. The new leaves were so fresh one could hardly recognize the plant. The plum tree too had put out many buds, making me think at once of a young girl’s hair. Reiko’s dark hair fell on both shoulders. The old plum trunk, wet with rain, was the blackest trunk in the garden.

As I unfastened my crescent jade from the watch chain, I asked Seta softly:

“Since then—no more dreams?”

“Didn’t you hear?” Seta did not answer; he only pulled his crescent jade from his pocket.

As we had agreed, we would let Haruko hear the jade bells. Haruko’s mother threaded the three stones together on a cord. She did not know that Seta and I had already joined two stones and listened together. She lifted the three stones before her eyes, shook them lightly, and looked toward Haruko’s portrait.

I too looked at the portrait. Was Haruko listening to this birdsong-like sound? I listened with all my attention.

The jade bells were like a low whisper wandering between life and death.

“Haruko used to come to your house often,” her mother asked me. “What did she say to you?”

“Ah…”

My daughter was two grades below Reiko and close with her, so Haruko often came to our house to play. Haruko had told me she was in love with a man named Seta; and I had done nothing but observe the beauty of a girl in love. Oddly, after Haruko died I felt closer to her.

Haruko’s mother handed the jade bells to Reiko. As before, Reiko hung them around her neck, shaking her head and shoulders to let us hear. Yet this time I felt no sensory shock as before; I did not imagine whether Haruko had let Seta hear the sound while confessing love. Instead I felt something subtler: that her sister seemed to have inherited her fate.

If Seta truly returned his stone, I too intended to return mine—back to this younger sister.

In the misting rain, the sheen of the garden’s green leaves lit Reiko’s face, and lit Haruko’s portrait as well.